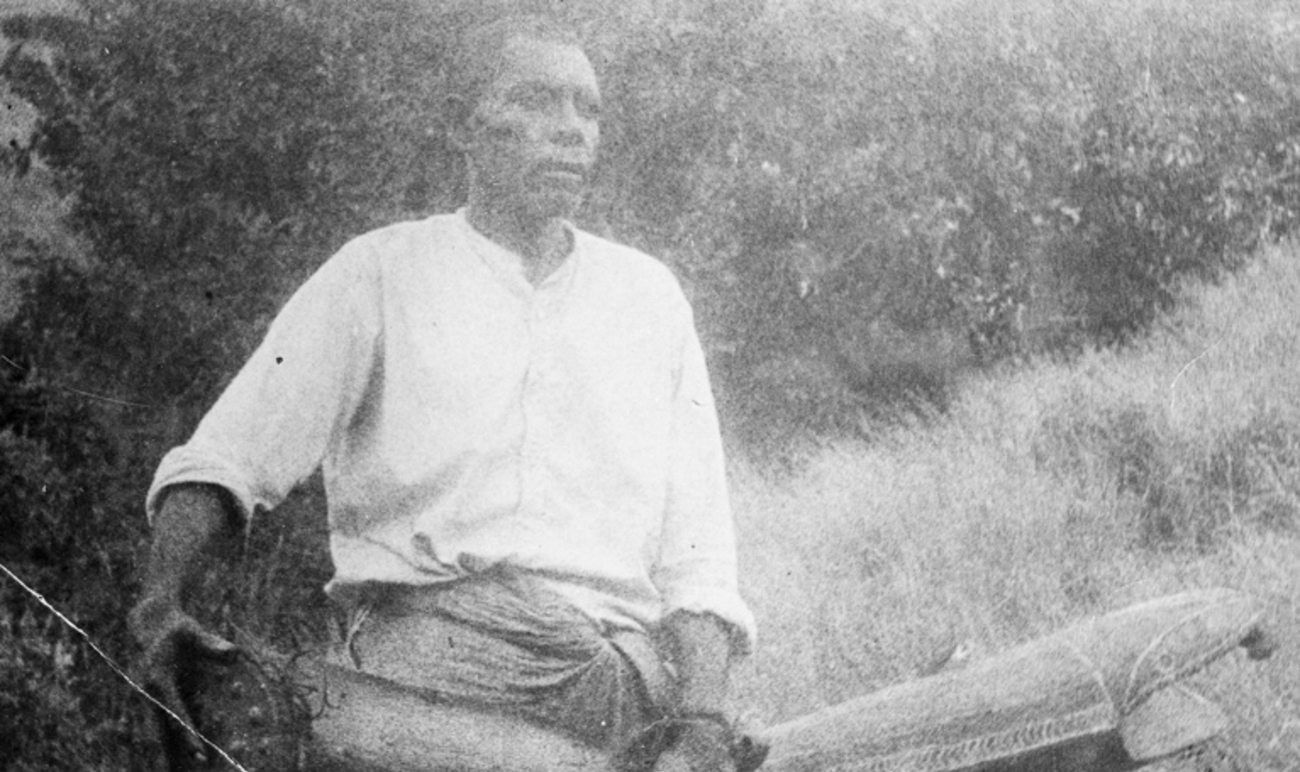

The efforts of the Gurindji to reclaim their ancestral land became one of the emblematic events of the land rights struggle in Australia. In August 1966 a group of Aboriginal pastoral workers, under the leadership of Vincent Lingiari, walked of the job at the Wave Hill cattle stationed in the Northern Territory owned by the multinational British corporation headed by Lord Vesty. These workers were protesting decades of abuse, poor wages and inadequate living conditions provided by their employer.

The following year the Gurindji moved to Wattie Creek (Daguragu) a place of deep spiritual significance to them. Here they continued their struggle for another eight years. During this time the Gurindji cause garnered support from a wide range of groups in Australian society, including the union and student movement. Finally, on 16 August 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam handed over leasehold title to the Gurindji’s ancestral land.

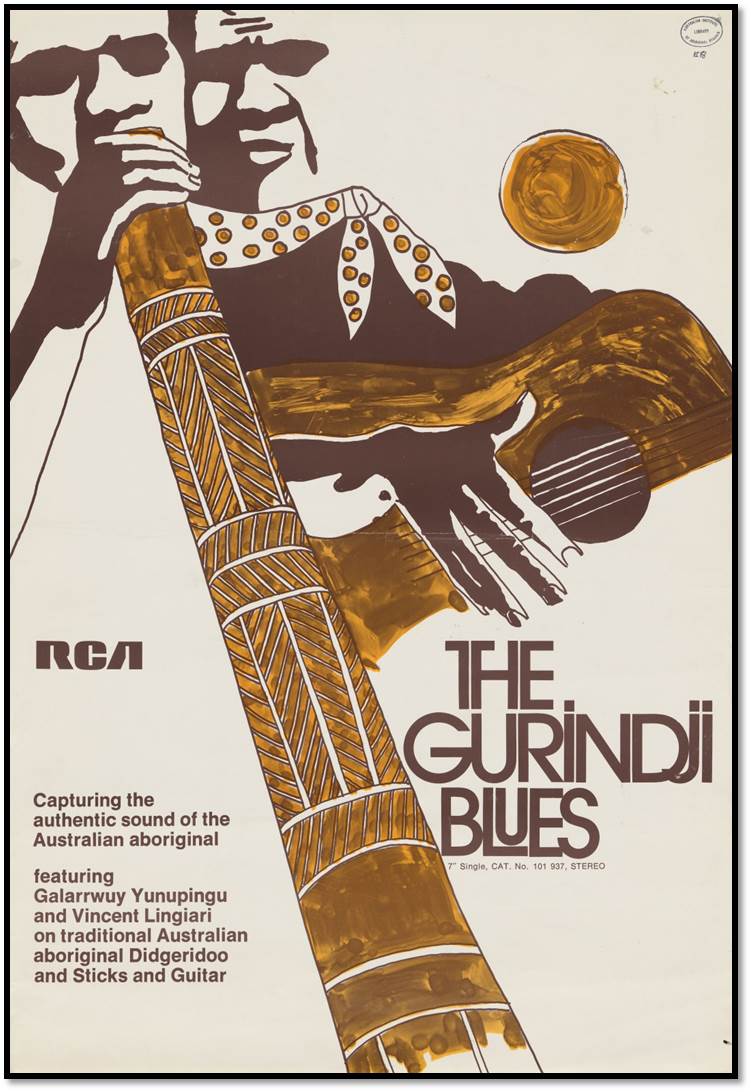

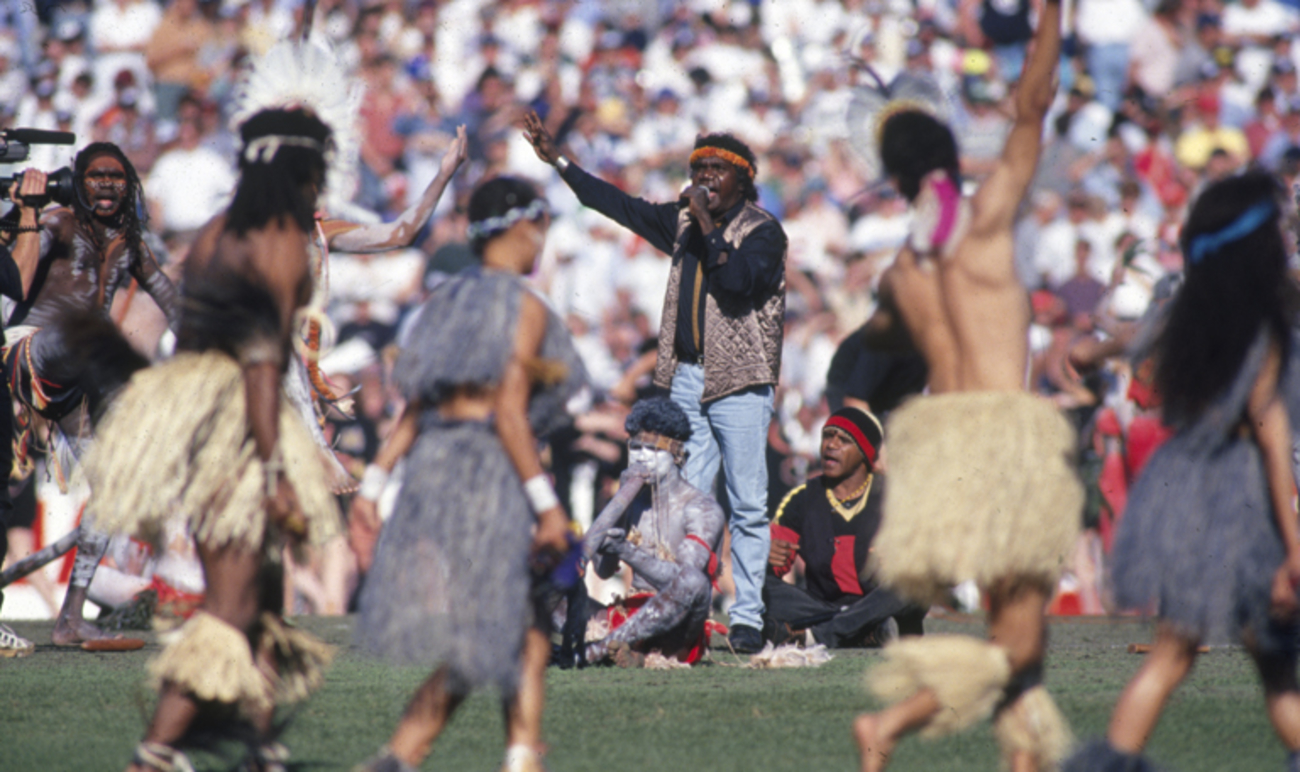

Ted Egan wrote The Gurindji Blues in 1969, during the height of the Gurindji land rights struggle. The song was a blistering critique of the living conditions endured by the Gurindji and the government’s inaction to resolve many of these issues. It features performances by Vincent Lingiari, Galarrwuy Yunupingu and Ted Egan.

The Gurindji Blues

Poor bugger me, Gurindji

Me bin sit down this country

Long time before Lord Vestey

Allabout land belongin' to we

Oh poor bugger me Gurindji.

Poor bugger blackfeller this country

Long time work no wages we,

Work for the good old Lord Vestey

Little bit flour, sugar and tea

For the Gurindji, from Lord Vestey

Oh poor bugger me.

Poor bugger me, Gurindji,

My name Vincent Lingiari

Me talk allabout Gurindji

'Daguragu place for we,

Home for we, Gurindji

But poor bugger blackfeller, this country

Government boss him talk long we

'We'll build you house with electricity

But at Wave Hill, for can't you see

Wattie Creek belong to Lord Vestey'

Oh poor bugger me.Poor bugger me, Lingiari

Still me talk long Gurindji

Daguragu place for we,

Home for we, Gurindji

Poor bugger me, Gurindji

Up come Mr Frank Hardy

ABSCHOL too and talk long we

Givit hand long Gurindji

Buildim house and plantim tree

Longa Wattie Creek for Gurindji

But poor bugger blackfeller this country

Government lawyer him talk long we

'Can't givit land long blackfeller, see

Only spoilim Gurindji'

Oh poor bugger me Gurindji

Poor bugger me, Gurindji

Peter Nixon talk long we:

'Buy you own land, Gurindji

Buyim back from the Lord Vestey'

Oh poor bugger me, Gurindji.

Poor bugger blackfeller Gurindji

Suppose we buyim back country

What you reckon proper fee?

Might be flour, sugar and tea

From the Gurindji to Lord Vestey?

Oh poor bugger me.

The song was a response to the then Commonwealth Minister for the Interior, Peter Nixon, who during a visit to Darwin said that if the Gurindji wanted to get some land, why didn't they save up like all other Australians and buy some. This was repeated by the Opposition leader Gough Whitlam during question time in Parliament. This comment became emblematic of the perceived indifference by many in the government to the plight of the Gurindji. At the time Egan was working as a Research Officer at the Council of Aboriginal Affairs under Nugget Coombs and W H Stanner. Other staff members at the council included prominent Aboriginal figures Charles Perkins and Reg Saunders. After the song was released Nixon's Department Head, George Warwick Smith insisted Egan be sacked for his role in writing the song. Nugget Coombs responded that he thought it was a “bloody good song” and that it was a “succinct appraisal of the government’s pathetic performance”.

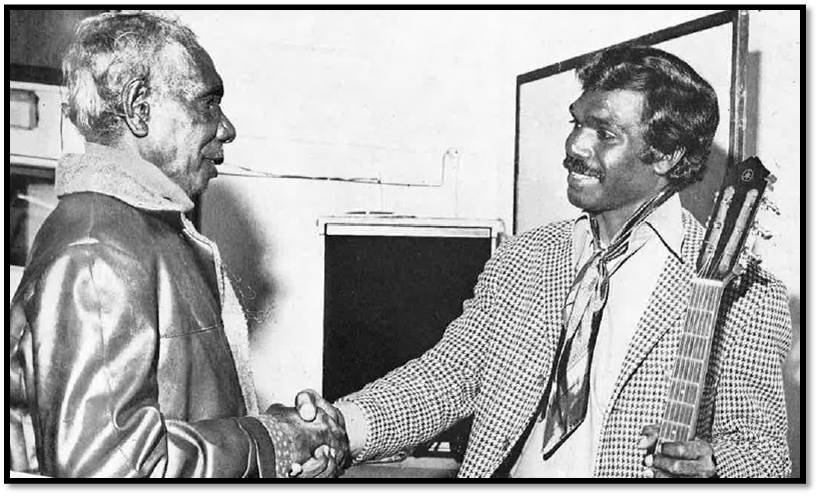

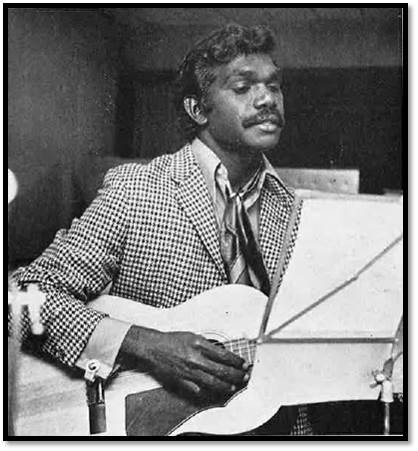

In 1971 the Aboriginal Arts Board, through the influence of Jenny Isaacs who had been working as Nugget Coombs secretary in 1969, arranged for Vincent Lingiari and Galarrwuy Yunupingu to travel to Sydney in order for them to participate in the recording of the song at the Natec Sound Studios. Egan recalls that Vincent Lingiari had difficulty hitting some of the high notes in the song during rehearsal so the decision was made for Lingiari to do the spoken word introduction and for Egan to take over singing duties with Galarrwuy Yunupingu who also would also sing the song This Tribal Land, the B-side of the record. Yunupingu said that he wanted to make the record “to get the message across” and so that the “people of Australia would write to the Prime Minister and protest about Aboriginal land rights”.

The record was used as a fundraising vehicle, initially for the Gurindji cause, but later to promote other forms of Aboriginal activism. Shortly after the song’s release Ted Egan wrote to John Zakharov, a union activist and secretary for the Gurindji Campaign in Melbourne. Egan noted his disappointment at the commercial distribution and initial sales for the record. He expressed some concern that the use of the word “bugger’ might have been part of the reluctance of radio stations to play it. In one letter he suggested that the single should be sold instead of “campaign buttons” to raise funds for the Gurindji.

Not only would the campaign profit from the actual sales of the records but Egan would also contribute any royalties he might have received from their sale. At the time of the letter race issues were high in many activists minds as this coincided with the turbulent Springbok tour of Australia. Egan hoped to tap into this heightened interest and concern to further the cause of Aboriginal rights in Australia.

The Gurindji campaign in Sydney also sold copies of the record at Christmas time and encouraged the Waterside Workers to sell records to raise fund for the Tent embassy. Ted Egan has mentioned that Aboriginal activists Chika Dixon and Michael Anderson were fans of the song and sold many copies.

Vincent Lingiari became one of the iconic figures in the struggle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to regain the rightful possession of their traditional lands. Galarrwuy Yunupingu would go on to lead the Northern Land Council and has received numerous honours, including being named Australian of the Year, for his work for Indigenous rights. Ted Egan would pursue a long career in the music business and became the Administrator of the Northern Territory from 2003-2007.

The Gurindji Blues brought together a diverse range of groups and individuals to further the cause of the Gurindji people and of Indigenous land rights in Australia. It did not shy away from presenting a stinging criticism of Australia’s treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It can also be regarded as one of the original land rights ‘anthems’ that paved the way for songs by Indigenous and non-indigenous performers such as Yothu Yindi , the Warrumpi Band, Kev Carmody and Midnight Oil.