‘When you look at those sorts of stories, you see the connectivity between all of the elements, between the sky, between the Earth, between the water, between magnificent sacred sites that are in the landscape that connect our people through this ancient wisdom and these ancient stories in song.’ — Dr Anne Poelina, Nyikina Warrwa

Songlines carry the first story of this land. But, with the passing of elders, the knowledge of these songlines is in danger of disappearing.

AIATSIS, through its Foundation, has supported a project to record, map and maintain the ceremony of the Marlaloo songline; a songline that runs from Balginjirr to Marlaloo in Western Australia and covers a significant part of the Martuwarra (Fitzroy River).

The song cycle has not been sung for more than 40 years. The two remaining Elders and knowledge holders, Rosie Mulligan and Madeline Yanamara, were worried that the knowledge would disappear.

With time passing, the Elders have chosen two young leaders, Edwin Mulligan and Mark Coles Smith to hold the songs and ceremony for now and the future.

The Marlaloo songline is about two serpents travelling through the cultural landscape naming places along the way. One serpent rises up from Linagoodung Cave (Mount Anderson Cave) and travels through Nyikina Country to the beginning of Mulaloo Country where he is confronted by the serpent from Mulaloo.

Mark Coles Smith and Edwin Mulligan are pictured above performing the face-off between the two serpents.

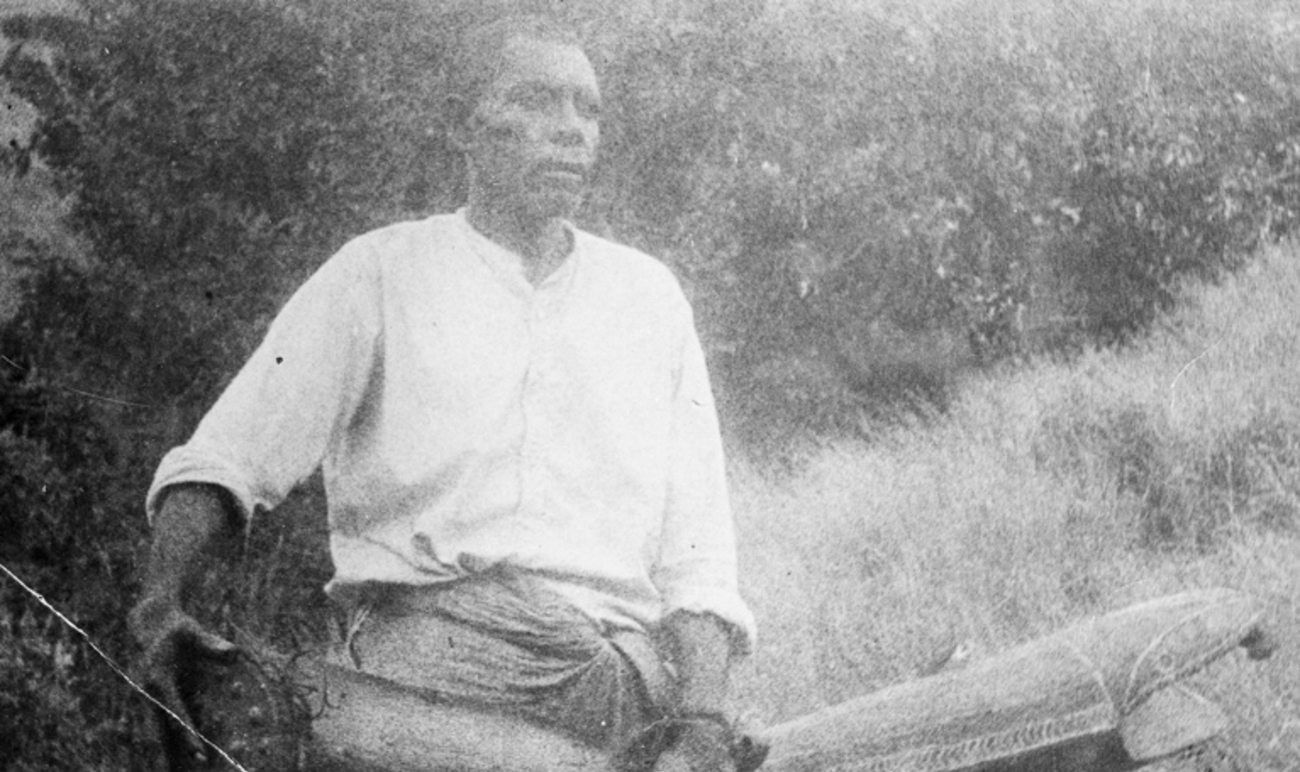

Elders Rosie Mulligan, Madeleine Yamera and Jeannie Warbie performing the Marlaloo songline.

Mapping the songline

‘It's a very, very beautiful thing. But it's also a highly emotional thing, because what we're doing is that we are evoking the songline that has been anciently embedded in the cultural landscape. And we bring it to life with the voices in the singing of the elders. And so we were able to travel and map the songlines.’ — Anne Poelina, Nyikina Warrwa and Traditional Owner

Mapping a songline not only takes time it also has to be the right time. ‘We've been waiting, what we call in a circle of time for the right moment, and the opportunities for the elders to feel ready to share’, said Anne Poelina.

‘We wanted to be respectful and show that this was a great opportunity to be respectful to the land, but importantly, the songlines.’

The Marlaloo songline, like many songlines, is a shared story that traverses the cultural landscape linking people and places. Only the right people can speak for Country, and following cultural protocols ensures that those who carry the knowledge and wisdom of the songline have the legitimacy and the authority to do so.

‘In terms of the stories, the song, the ceremony, the awakening of the landscape, with the right people to be in then in a position to say, "Okay, we have two very younger men who have come on the journey with us, they are Nyikina men, they are the ones that we should then bestow the legitimacy and the authority of the songline to."’ — Anne Poelina

With AIATSIS Foundation funding, the project team led by Elders, have now recorded and mapped the songline journey.

The Foundation aims to record songlines in 16 regions across Australia in the next 10 years.

-

Transcript

First of all, I just want to confirm that [Anne introduces herself in language].

So I'm just introducing myself and my name is Dr Anne Poelina. And in my introduction, I said that I'm a woman who belongs to the Fitzroy River, the Martuwarra. But I am sharing today on Juukanin Yara country in my home brew.

I wanted to share with the listeners today, this opportunity to talk about the Balginjirr songline. And it's a very momentous time for us because we've been waiting since 1976, to map this songline. And we've been waiting, what we call in a circle of time for the right moment, and the opportunities for the elders to feel ready to share. So it's been a very, very long journey.

And what was very interesting was many years ago, in 1976, there was a very big Indian Oceania festival in Perth, where my elders from Noonkanbah went to Perth to participate in a ceremonial festival of sharing what is, you know, what is the amazing culture that indigenous people bring from the Indian Ocean perspective. And so this story was recorded in the songline was recorded many, many years ago.

But I wanted to be able to have the time to work with my senior elders from Noonkanbah to look at how we would map this songline process because it's quite complicated. It's not just Oh, now I’m going to go and map this songline project, because there's a lot of cultural protocols involved in mapping a songline.

And we wanted to be respectful and show that this was a great opportunity to be respectful to the land, but importantly, the songlines. So the Balginjirr songline project has been able to receive some very, very important resources from the AIATSIS project. And it's an amazing project that AIATSIS is leading and definitely want to give a plug for the great work that's coming out of that, because without this bit of seed investment, we would not have been able to do the project.

So it's a very, very powerful opportunity because it allows me living on my country at Balginjirr, Balginjirr is a very, very big sacred ridge. It's a huge sacred site that runs 26 kilometres along the land, cultural landscape. And then it does a deep dive under the Fitzroy River or the Martuwarra, and it comes up just outside of Broome.

And it's amazing story because it starts in Balginjirr and a beautiful living water system or a billabong called Gulminarr. And Gulminarr is an abbreviation of coolamon. And those of you that know the coolamon is a dish that you know can carry water, can carry food, can carry a baby. So it's a very, very special place.

And about 10 years ago, I had an opportunity to stand at my billabong and hear a senior elder tell the story of how two serpents commenced the journey of this songline of Balginjirr. But it turns the other way. And this songline goes from Balginjirr to Mullaloo.

And so we've been working with the senior elders, we've been working with our amazing young filmmakers. And we had an opportunity to go on country and map the songline. So as I said, the songline starts at Balginjirr, and it's a story about two serpents that travel through the cultural landscape, naming places and actually having, in a way a contest of strength between a serpent that travels from what we call Minagooda, and which is the Mount Anderson cave. And so this serpent rises up and it starts at Linagoodun Cave and then it comes back to Balginjirr.

And then from there, it travels across the cultural landscape, travelling through the countryside going from the cave, called Linagoodun Cave, which is the place is called Juma danga which in the western name is called Mount Anderson.

And this is a huge mountain that is in the middle of the Fitzroy River. And this serpent rises up from Linagoodun Cave, and travels through the cultural landscape. And as they travel, they come to significant spots along the country. And we named them and we were able to GPS and record them and capture this amazing footage using drones and working with our elders.

So it's a very, very beautiful thing. But it's also a highly emotional thing, because what we're doing is that we are evoking the song line that has been anciently embedded in the cultural landscape. And we bring it to life with the voices in the singing of the elders. And so we were able to travel and map the songlines and, and have all of that, but we came to a place very, very close to Noocumbah, and Noocumbah is my grandmother's country.

My great grandmother came in from the St. George range around about 1867, there was a huge massacre there. And most of her family were slaughtered, murdered, whatever description you want to hear. But she was brought into Noocumbah. And it's very, very interesting because I'm nearly 65 years of age. And this journey took me to a place which is half an hour from my grandmother's country. And it is just absolutely amazing.

So we went to the place called Mullaloo. Because the Balganjirr songline is actually called Mullaloo. And so we come to Mullaloo and it is I just, you know, sat there looking at the lake, and it was just teeming with every kind of bird you could think of.

And then I look back in the distance, and I could see St George Range, Thundera, we call it in our language, but it was almost like I was sitting there looking into a world that had my whole world before me, in terms of this was my grandmother's country.

And then I was looking back into my great grandmother's country. And all of this was right in front of me. And it was, in a way a preface door and had the Mullaloo, the lake in front of it. And there were every kind of bird that was sitting there. And as we walked through the Country, the elders were telling us the story of how the two serpents had had actually rose up and were in a battle against each other.

So the serpent from Linagoodun Cave came through, Nginarr Country from the lower Nginarr Country to the beginning of the Country, which was Mullaloo. And the serpent from there said, ‘Hey, this is my patch, don't come here trying to bring in your law and your ways of doing business. This is my, my territory’.

And so in the songline, there was, we were able to create, you know, two serpents that the two young men, young, they're in their 40s, we're able to then have the transformation and the legitimacy and the authority of the songline to be then bestowed to them.

So we had to go to countries, so countries could see that we were legitimate, and that the transfer and his knowledge and wisdom, were going to Nginarr men who were ready to carry the songline into the future, by learning and any engaging country now. So it's very, very powerful.

And then from there it triggered other stories in terms of the serpent from Mullaloo then went to a place called Muja or Fossil Downs. And there is, you know, danced and created the river system.

And then it turned back and came to Mullaloo, and at the fight of Mullaloo with the strength of the serpent from there stood up. And basically, they had this fight where it created a huge tornado. And in the story, it really made me reflect because when the elders started to talk to me about it, it showed that not only do we have a songline that shows that Mullaloo is where the serpent is, but it brought in a contemporary context of an actual tornado being caught being created. And sucking up.

When I heard donkeys and sheep and cattle. It made me realize that this actual event that took place was a songline from the beginning of time, but had context in terms of showing that it had relevance during the pastoral period. So it was very, very interesting in terms of that exploration.

But what it did was it evoked the country, it showed the country that we were the legitimate ones to be able to stand, record the song, but transfer to our young people.

So in the film that we've produced for AIATSIS, we've captured this story in about three to five minutes, which is amazing, because as I said, I've been waiting since 1976, for this opportunity.

But it captured this songline and it allowed us to then create a new modern dance. So when you see the film, you'll see the two men stand out and the serpents are there and it was very, very interesting because the day before I had to assume that, okay, if we've got two serpents fighting, then there is a whole performance just in the act of fighting.

But no. When we did the dance the others said no, we must stand still and the two servants must eyeball each other. And in a way they engaged in an invisible dialogue of how they will giving agency to themselves, how they were giving authority to say, Okay, you've come to my place Mullaloo. I'm going to have this fight, and then I'm going to send you back because I'm more powerful.

So it was very, very interesting in terms of the stories, the song, the ceremony, the awakening of the landscape, with the right people to be in then in a position to say, Okay, we have two very younger men who have come on the journey with us, they are Nginna men, they are the ones that we should then bestow the legitimacy and the authority of the songline to.

So these two young men is Edwin Mulligan, Edwin is Warlminjarri Nginna man and Mark Cole Smith. So both of these men have been through this process.

So there's been a huge investment in terms of going on country being with the elders travelling through the landscape, doing ceremony at each particular spot that we went to, to end up with a story that can reflect the meaning and the value of songline.

Songlines are alive

‘They are profound, they are still alive, because one of the things we say, as Indigenous people is, the land is alive, the rivers are alive, the Country is alive, because it holds memory.’ Anne Poelina

Songlines are both ancient and contemporary. They trace the journey of ancestral beings and how things came to be. They are songs and stories of events and navigational routes through Country.