The AIATSIS Collection holds a very precious copy of what is considered to be the first known use of written English by an Aboriginal Australian. It is a copy of what is known as the 'Bennelong Letter' and represents a seminal work in Australian Aboriginal literature.

Woollarawarre Bennelong was a Wangal man from the south shore of the Parramatta River who is believed to have been born in about 1764. He formed a friendship with Governor Arthur Phillip who took him and his kinsman Yemmerrawanne to England in 1792 where Bennelong spent three years. During this time Bennelong undertook reading and writing lessons.

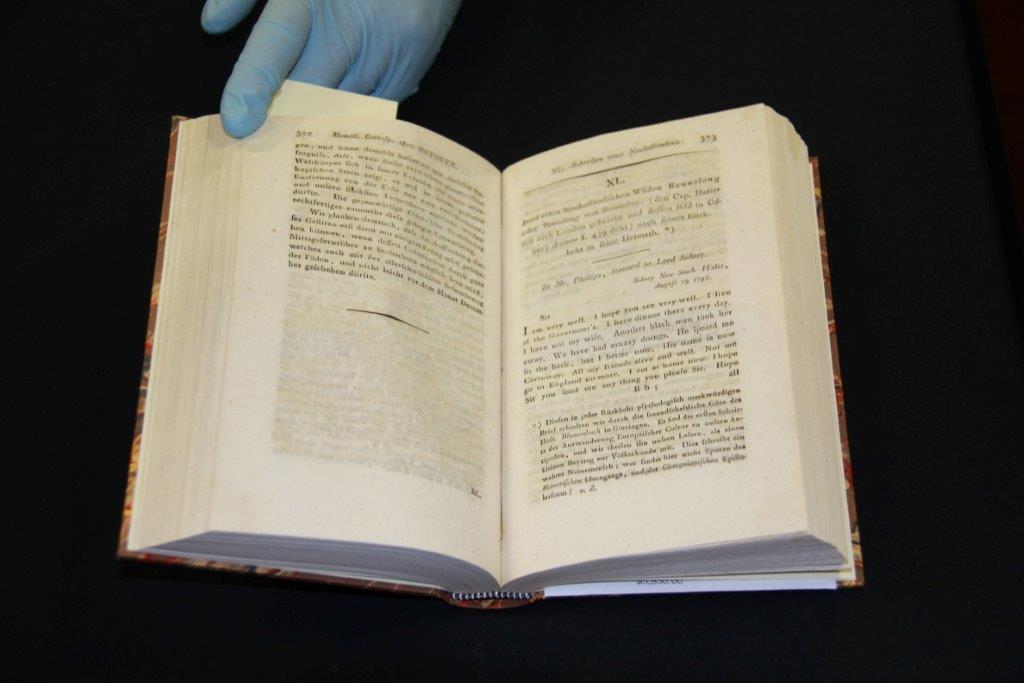

The letter is included in the 1801 German publication: “Monatliche Correspondenz zur Beforderung der Erd and Himmelskunde” (Monthly Correspondence for the Promotion of Geography and Astronomy) edited by Franz Xaver Freiherr von Zach. Von Zach, a Hungarian astronomer, accepted the letter for publication from the German anatomist Johan Friedrich Blumenbach having received it from Joseph Banks who in turn acquired a copy from Governor John Hunter.

The original letter was dictated by Bennelong on August 29, 1796 from Sydney and is addressed to ‘Mr. Phillips, Steward to Lord Sidney [sic]’. Historians have not been able to find a steward to Lord Sidney named Mr Phillips and this has led to speculation that the letter may in fact have been aimed at former Governor Phillip whose second wife nursed Bennelong when he was ill in England.

The letter states:

‘Sir, I am very well. I hope you are very well. I live at the governor’s. I have every day dinner there. I have not my wife; another black man took her away. We have had muzzy doings; he speared me in the back, but I better now; his name is Carroway. All my friends alive and well. Not me go to England no more. I am at home now. I hope Mrs Phillips is very well. You nurse me madam when I sick. You very good madam; thank you madam, and hope you remember me madam, not forget. I know you very well madam. Madam, I want stockings, thank you madam. Send me two pair of stockings. You my good Madam. Thank you Madam. Sir, you give my duty to Lord Sidney. Thank you very good my lord, very good. Hope very well all Family, very well. Sir send me you please some handkerchiefs for pocket. You please Sir send me some shoes. Two pair you please. Bannelong.’

It is believed that the letter was dictated to a scribe rather than written by Bennelong himself. It is unlikely that Bennelong would have had access to the writing equipment required as it would be unusual for the scribe at the Governor's House to have lent him his writing accoutrements. Furthermore, the role of a scribe in the eighteenth century was a very specialised role which required training and recording the dictation of others.

Whilst the letter is written in English, the Aboriginal voice of Bennelong comes through in expressions such as ‘his name was Carroway’. ‘Carraway’ or ‘caruey’ (white cockatoo) was a young uninitiated Cadigal man who appropriated Bennelong’s wife Kurubarabula[i]. The word ‘muzzy’ is thought to represent a transcription error of the word ‘murri’ which means ‘big’ in the Sydney language.

The request for stockings, a handkerchief and shoes may seem inappropriate in this context, but from an Aboriginal etiquette point of view it reflects the practice of reciprocity and gift exchange that Bennelong would have expected from his English hosts.

Author Keith Smith has successfully argued that Bennelong was a master politician, brokering alliances among various factions via marriages for himself and his sisters in order to secure, and later extend, his leadership within his Wangal clan[ii]. This account challenges the oft told story that Bennelong was shunned by Europeans and his own people alike on his return from England.

Bennelong died in 1813 and is buried in the present day suburb of Putney in Sydney.

The original of the letter has never been found.

References

[i] Smith, Keith Vincent 2012. Bennelong’s letter expresses authentic Aboriginal voice. The Australian, Dec 29.

[ii] Smith, Keith Vincent 2009. Bennelong among his people. Aboriginal History, Vol. 33, pg.