The AIATSIS Australian Indigenous Languages Collection was established in 1981. It contains over 4300 titles and was placed on the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register in 2009.

The Languages Collection includes diverse materials in most Indigenous languages. We hold early readers and story books produced by communities and language centres during the bi-lingual period in remote communities as well as unpublished manuscripts of language materials collected during the earlier years of the Institute, when it was the major source of funding for linguistic research projects.

These two extremes are connected. The initial development of the early readers required a writing system, which in turn requires an expertise in representing spoken language in written form.

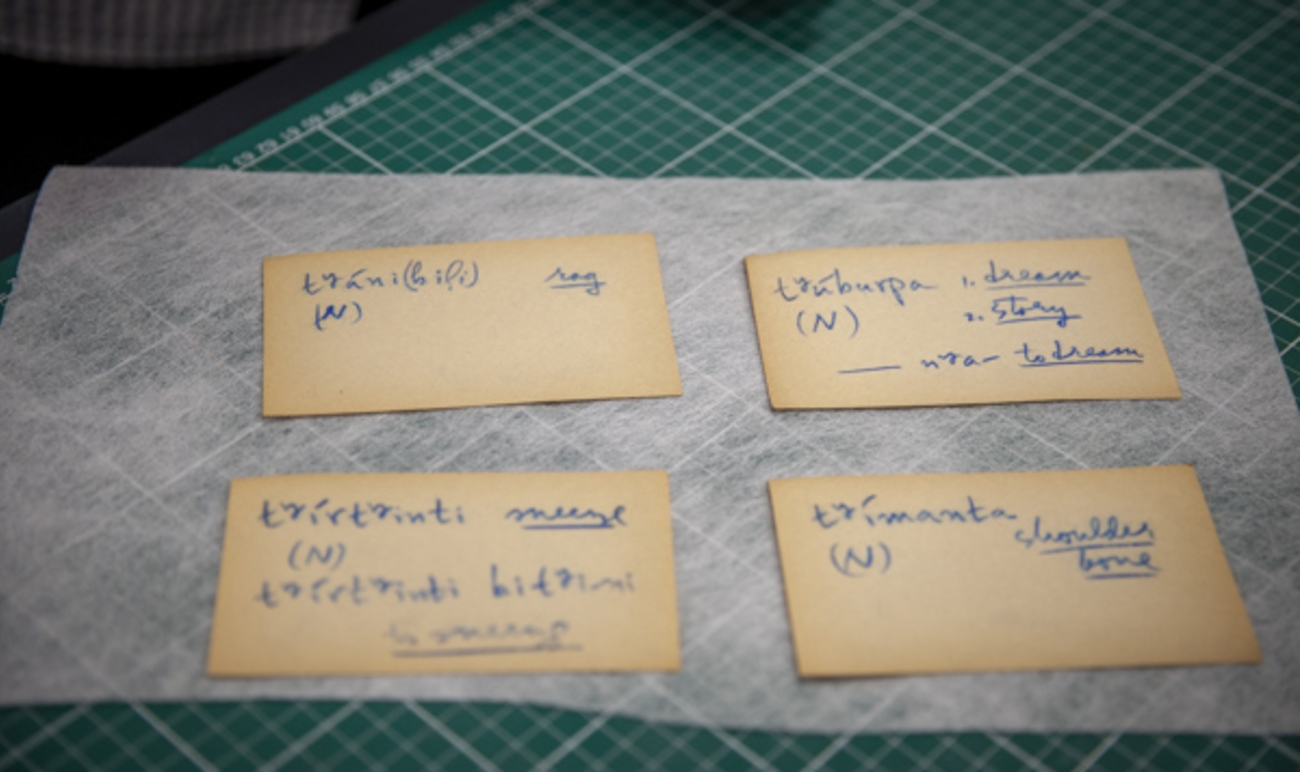

Unpublished handwritten or audio recordings containing ‘raw’ data are analysed by linguists to establish the sound, word, word building, phrase building and sentence building patterns in a language, thus revealing the grammar as expressed by speakers. Producing a grammar and lexicon (a dictionary of words, prefixes, affixes and suffixes) provides a consistent basis for a writing system, and thus the means to produce written texts from spoken texts.

Indigenous languages do not exist in isolation, they are related to each other either ‘genetically’ or by being in contact as geographic neighbours.

The languages share a set of sounds. Not all languages have the same sounds, but they draw of the same set and have predictable variations. Thus the writing systems used across the continent provide consistency for speakers and learners and support our understanding of the relationships between languages.

Having this background around spoken languages provides a framework to interpret historical materials about languages that are no longer handed down as first language to the next generation. A knowledge of English writing conventions contributes, because this is the vehicle most amateur researchers used to record spoken language.

For example, the written doubled consonant in words like skipping <pp>, mitten <tt>, running <nn> and dollar <ll> indicates that the preceding vowel <i, u, o> is ‘short’. So a doubled consonant in an early wordlist helps to interpret the quality of the preceding vowel. Similarly, the known Indigenous languages sounds, such as words beginning with [ng] and the subtle but important differences between various [r], [rd], [rr] sounds, were often missed by early language recorders.

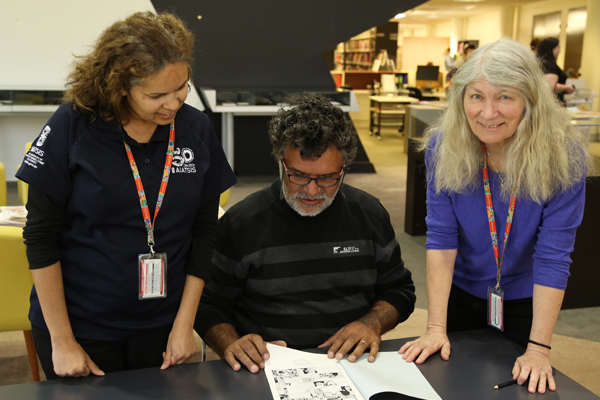

The following items from the AIATSIS Collection drew the attention of visiting academic Dr Ray Kelly (University of Newcastle) who has been involved supporting research of three east coast languages: Dhanggati, Gathang and the language from the Hunter River and Lake Macquarie.

With AIATSIS linguists Rhonda Smith and Amanda Lissarrague, we enjoyed storybooks from Gurr-goni (N75) and Walmajarri (A66), an early reader in Warlpiri (C15) and two comic books, one in Warlpiri and another in Ndjebbana (N74), as well as a Dhanggati (E6) language learning resource.

Storybooks from Gurr-goni (N75) and Walmajarri (A66), an early reader in Warlpiri (C15) and two comic books, one in Warlpiri and another in Ndjebbana (N74), as well as a Dhanggati (E6) language learning resource.

Storybooks from Gurr-goni (N75) and Walmajarri (A66), an early reader in Warlpiri (C15) and two comic books, one in Warlpiri and another in Ndjebbana (N74), as well as a Dhanggati (E6) language learning resource.

The alpha-numeric codes keep track of language names which inevitably come with a variety of historical and current spellings, and sometimes even a change in name. AustLang is a research tool which helps identify a language.

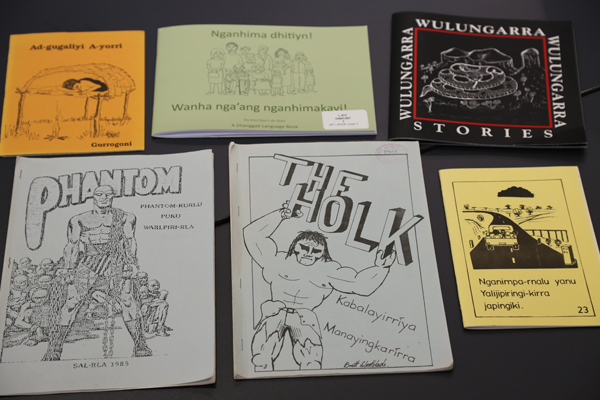

Top row, left to right:

- Marsha Ashwell, 1989. Ad-gugaliyi a-yorri. The man slept. Story by the Boburerre people, Gurrogoni language. Maningrida NT: Maningrida Literature Production Centre. This is a first language literacy development resource. Gurrogoni (N75) is a language from north central Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.

- Ray Kelly and Amanda Lissarrague. 2011. Nganhima Dhitiyn! Wanha nga’ang nhanhimakayi! Do this! Don’t do that! A Dhanggati language book. Nambucca Heads NSW: Muurrbay Aboriginal Language and Culture Cooperative. Dhanggati language learning resource, illustrative book and a CD. Dhanggati (E6) is the language from the Macleay Valley NSW.

- Yangkana Laurel, Papayi Laurel, Lucy Bell, Elsie Laurel, Stephen Laurel. 1997. Wulungarra stories in Walmajarri and English. Illustrations by the authors. English version by Laurel Yangkana. Fitzroy Crossing WA : Kadjina Community. Stories in first language. Walmajarri (A66) is a language from the Great Sandy Desert region, northern Western Australia.

Bottom row, left to right:

- Phantom: Phantom-kurlu puku Warlpiri-rla. Darwin Community College. School of Australian Linguistics. No author or date recorded. Comic strip of the Phantom adapted into Warlpiri. Warlpiri (C15) is a language from Central Australia. It is one of the few Indigenous languages still spoken as first language by the youngest generation.

- The Holk Kabalayirriya Manayingkarirra. Brett Westblade. Translated into Njebbana language by L. Djabibba. Maningrida NT: Maningrida Literacy Production Centre 1981. Comic strip of the Hulk adapted into Njebbana. Njebbana (N74) is a language from Central Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory.

- Janet Nakamarra Long. 1981. Nganimpa-rnalu yanu Yalijipiringi-kirra japingki. Warlpiri sentence reader No 23. Produced at Willowra School. Printed at Warlpiri Literature Production Centre Inc. Yuendumu. An early first language literacy development resource in Warlpiri (C15).

Language items in Mura, the AIATSIS catalogue, can be found in the 'Links' tab for any language on the AustLang database.

The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages is a digital collection of books produced during the bilingual period in the Northern Territory, when children could develop literacy skills in their first language.