‘Against Native Title’ is a book about one Aboriginal group’s experience of the native title claims process. The book has a central character, a woman called Sue Coleman Haseldine. Aunty Sue is a skilled storyteller — a warm, wise and funny person — and a vehement critic of native title. In this book I try and understand why a respected Indigenous community figure has come to take a stand ‘against’ native title, which promises to recognise Aboriginal rights in land.

Sue is a senior Kokatha woman, who lives in the outback town of Ceduna on the far west coast of South Australia. I came to know Aunty Sue through a series of personal connections. In the early 2000s I was involved in an environmental campaign against a nuclear waste dump in northern South Australia. Friends from that activist time had gotten to know Sue. In late 2006, I travelled out to Ceduna, sleeping on a rusted spring bedframe and thin foam mattress out on the verandah at Sue and her whitefella husband Gary’s wheat farm. Aunty Sue spent the week acting as a guide for me and two friends: we picnicked out bush, lost money on the Melbourne Cup, and waded into warm water at low tide to claw razor fish out of the mud flats.

One of the reasons Sue welcomed interested outsiders like me into her world was because she was deeply concerned about the extensive mineral exploration underway in her country and was seeking supporters.

Aunty Sue is ‘against mining’, just as she is ‘against native title’. In time I grew to understand that the two issues are inextricably linked. Sue perceives that native title legislation compels Aboriginal groups to accept mining; with no right of veto, negotiations with mining companies can become wearisome and divisive.

In early 2008 I moved to Ceduna to begin twelve months of fieldwork for my PhD. Originally I intended to scrutinise the relationship between environmentalists and Aboriginal people in this area, which Sue had sought to foster. I wanted to turn the researcher’s gaze back onto non-Indigenous people, instead of reproducing the colonial dynamic of studying ‘the other’. But Sue’s family group’s predicament was compelling, and there was nothing ethical about looking away. So I began to probe deeper into their disillusionment with native title, which has complex origins and a range of confronting but also inspiring effects. This whole process of building relationships and coming to understand something of the situation in Ceduna took a long time, and eventually resulted in my book, ‘Against Native Title: Conflict and Creativity in Outback Australia.’

The conflict part of the title refers to the social divisions that formed in Ceduna through the process of engaging with native title. From Aunty Sue’s perspective the native title claim turned to the colonial archival record as a source of truth in ways that undermined her understanding of her identity, history and relationship with Country. It is also a reference to the bitter conflict over the question of mining, a fight that has receded in this region as the mining boom petered out.

The creativity in the title refers to Sue’s family’s determined and ingenious efforts to renew their relationships with precious water sources and sites of cultural significance with limited resources. By travelling out bush to tend to rockholes Aunty Sue’s family continue to care for Country as their ancestors once did.

Writing this book was difficult at times. I respect that many Aboriginal people embark on lengthy and ultimately rewarding struggles to have their rights as native title-holders recognised. And real benefits can flow from the agreements that native title groups negotiate with mining companies. But I also wanted to take Aunty Sue’s cynicism seriously and to share what she had taught me about their experiences with a broader audience.

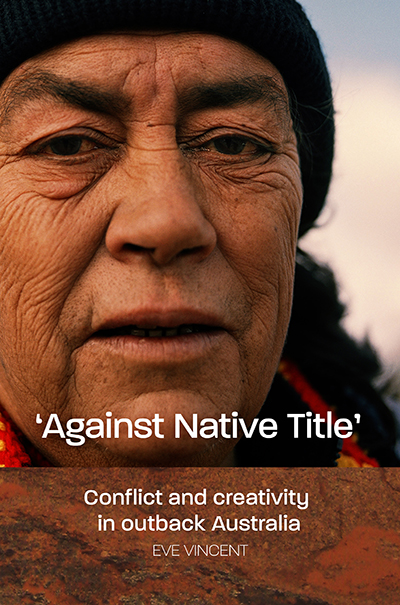

It was important to me to publish this book with Aboriginal Studies Press. I didn’t want to wrench Aunty Sue’s story out of the world it belonged to and tell it in ways that the people I was writing about would find alienating and weird. Aboriginal Studies Press understood this commitment to writing a story that we hope will reach the public. And so Aunty Sue’s creased and inquiring face on the cover invites us into an ethical relationship with another, drawing the reader into her life and offering the chance to hear her insights into the world.

Order your copy of "Against Native Title" from Aboriginal Studies Press.