The histories of missions, reserves and stations in this country are diverse and often dark. Each state and territory had their own policies and definitions which were introduced at different times and in different ways.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many First Australians were forced from their Country and on to missions, reserves or stations. It was not unusual for families to be separated and sent to different areas, sometimes across state borders, with no idea of where their loved ones ended up.

What were missions, reserves and stations?

Broadly speaking, there were three types of spaces set aside by different governments specifically for Aboriginal people to live on. These definitions varied between each state and territory, but they can loosely be defined as:

- Missions were often created by churches or religious individuals to house Aboriginal people, convert them to Christianity and prepare them for menial jobs. Most of the missions were developed on land granted by the government for this purpose.

- Reserves were usually parcels of land set aside for Aboriginal people to live on and were not managed by the government or its officials. People living on unmanaged reserves might receive rations and blankets from the state or territory government, but often remained responsible for their own housing.

- Stations or ‘managed reserves’ were generally managed by officials appointed by the government. Schooling (in the form of preparation for the workforce), rations and housing were provided, and station managers tightly controlled who could, and could not, live there. The managers usually had total control over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander lives including legal guardianship of their children.

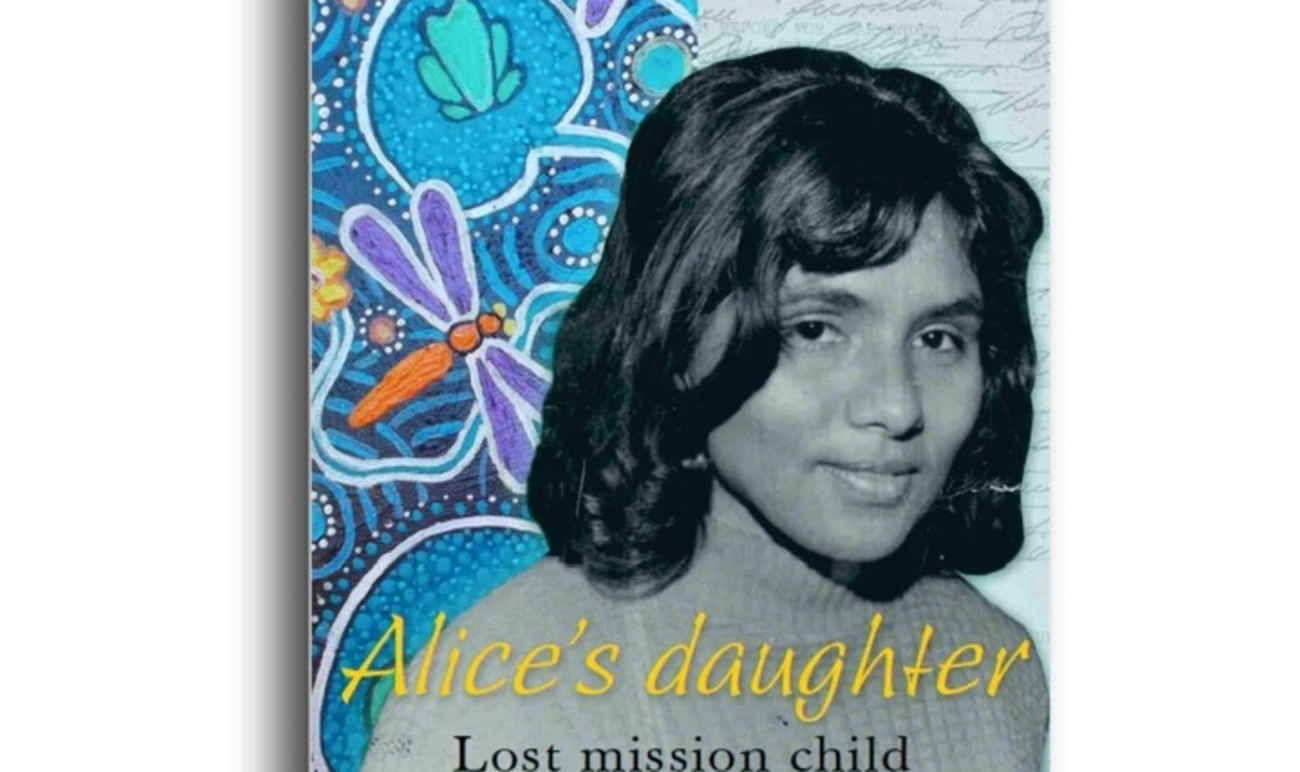

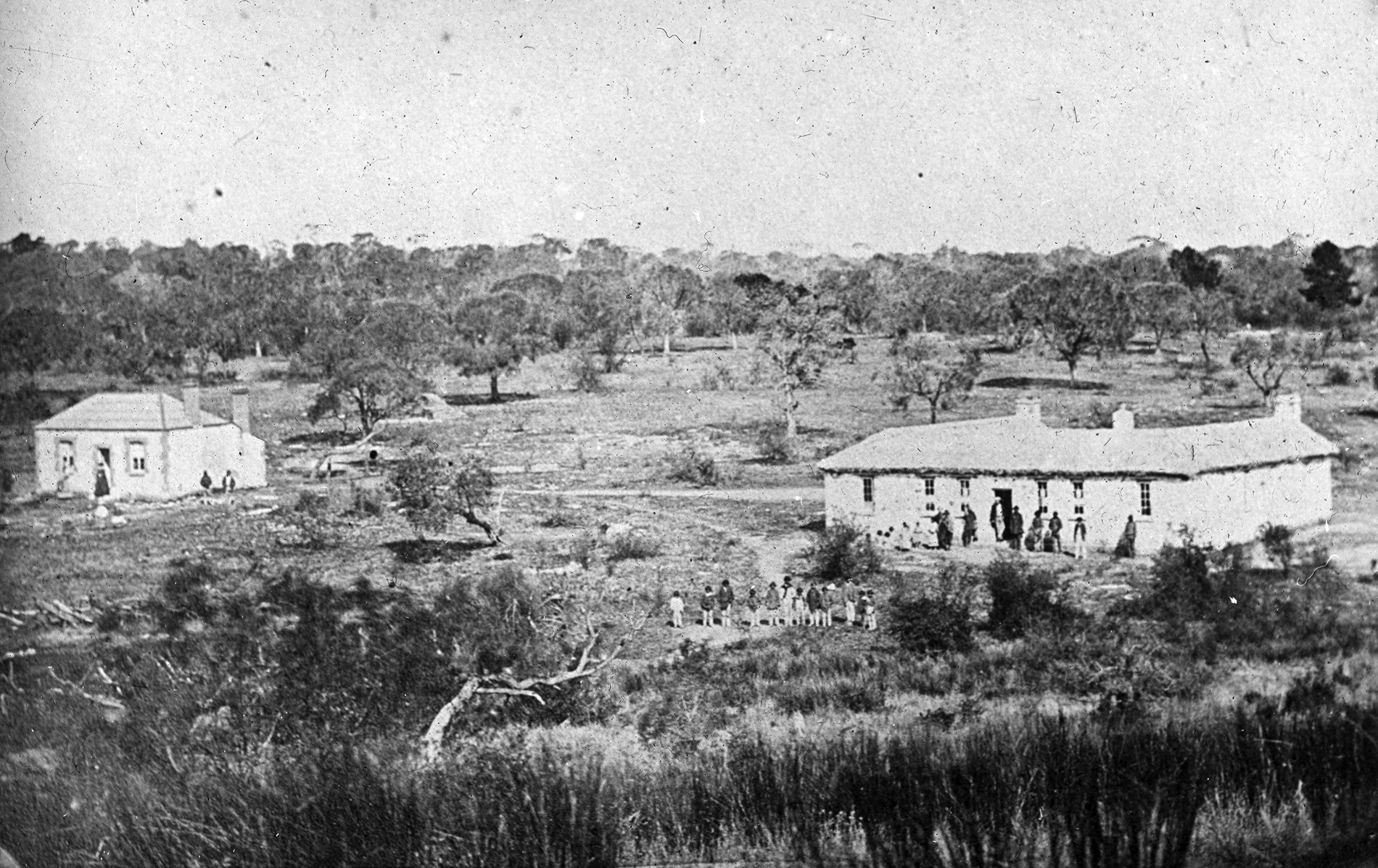

Point McLeay Mission, 1860. The mission included a school, church and community housing. Photograph by Herbert Read, AIATSIS Collection READ.H05.DF-D00025887.

Point McLeay Mission, 1860. The mission included a school, church and community housing. Photograph by Herbert Read, AIATSIS Collection READ.H05.DF-D00025887.

‘Protection’

These places were created and designed to ‘protect’ First Australians in a very patronising, paternalistic sense. Mainstream Australian thinking at the time was that Australia’s First Peoples were a ‘dying race’. Protectionist policies were developed reflecting this view.

The thinking was that all ‘full-bloods’ would eventually die off in these locations and that any children descended from white people could be ‘civilised’. During this time blood quantums (half-caste, quarter-caste, etc.) and ‘percentages of blood’ came into popular use as a tool for classification and control. These terms are so deeply offensive to First Nations Australians today and should never be used.

The Torres Strait

Protection policies reached as far as the islands of the Torres Strait and, like on the mainland, life was rigidly controlled.

The Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879 formally annexed the islands under Queensland control. In 1899 a local Protector was appointed on Waiben (Thursday Island) under the jurisdiction of the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1879, which was extended to include Torres Strait Islanders.

Many islands were declared ‘reserves’ and Islanders were placed under curfews and had to obtain permits in order to travel. The Protector took control of people’s earnings and Torres Strait Islanders had to seek permission to access their own money.

Control

Missions, reserves and stations were designed to erase peoples’ cultural identity. People were separated from their land and their families, and were not allowed to speak their languages, continue their cultural practices or teach them to their children.

Little to no background checks were done on the people placed in charge, nor was there much government oversight. Yet managers were given almost absolute control over the residents. For example, they were able to restrict their movements, control food rations and clothing allocations, control where they could work, if they could leave, who could visit, and even who they could marry. As a result, basic human rights were ignored and many abuses took place.

Today, most missions have vanished but some still exist, if in different forms. Depending on their governance structure, many have been reclaimed by the inhabitants and are now in their control. Some have become towns in their own right. Many are actively working to build their communities, improve the lives of their peoples and deal with the aftermath of what happened to them. One example of this is Cherbourg, Queensland. You can read about their community, history, and current endeavours on their website.

Archival records

It is not possible to give a single history of missions in one article. Policies varied between states and territories, as well as church groups, and most have their own histories about how and when they came to be, who ran them, how residents were treated, and so on.

There are some archival materials available in institutions across the country. These are usually fragmented and difficult to categorise. Most take the form of personal diaries of the missionaries, newsletters and church documents. Information about how to search these archives can be found in our family history section.

Organisations like the Aborigines Inland Missions (AIM) published newsletters which were written from the missionaries’ perspective and represented their interests. AIATSIS has digitised the full collection of AIM and Evangel newsletters.

To remove and protect provides the full text of the annual reports of all state and territory ‘protection boards’ and the subsequent government agencies.

Dawn and New Dawn magazines contain articles about the conditions and activities on reserves, stations, homes and schools throughout New South Wales. They have become good sources of information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family history research.

The map of New South Wales Aboriginal Missions, Stations and Camps shows the locations and provides information about Aboriginal reserves, camps, stations, children’s homes, and some unofficial settlements operating under the tenure of the Aborigines Protection Board (which was replaced by the Aboriginal Welfare Board in 1940) during its active years.