A brilliant Australian

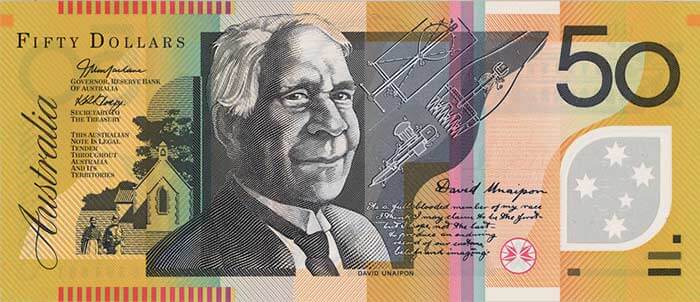

Have you ever looked at the Australian $50 note and wondered about the dignified man that peers pensively into the distance? Why is he looking so thoughtful? What was so special about him that he has been immortalised on our currency?

Here is a story about this man; one of our nation’s finest thinkers. A man curious about the world in all its physical and spiritual wonders. A man whose engineering genius was matched only by his gift for skillful prose.

He is David Unaipon, an inventor, writer, orator and campaigner. He spent much of his life transforming the minds of White Australia in the hope that one day Aboriginal people would be seen as equals.

In the beginning

So where does his story begin?

If you look to the right of Unaipon on the $50 note you might find a hint. There you will see shields. They are shields that belong to the Ngarrindjeri nation. A nation whose homelands span the Lower Murray, Coorong and Lakes area of South Australia. Ngarrindjeri people have lived here for millennia, drawing nourishment from Murrundi, the River Murray, which snakes its way through the landscape.

Unaipon is a Ngarrindjeri man from Point McLeay Mission, now known as Raukkan in the Coorong region of South Australia. Born in the late 1870s, Unaipon’s country, like many other First Nations, was invaded by white colonisers determined to wipe out Aboriginal peoples’ identity, cultures and ways of life. There was violence in the confrontation. But there was also survival.

Mission life

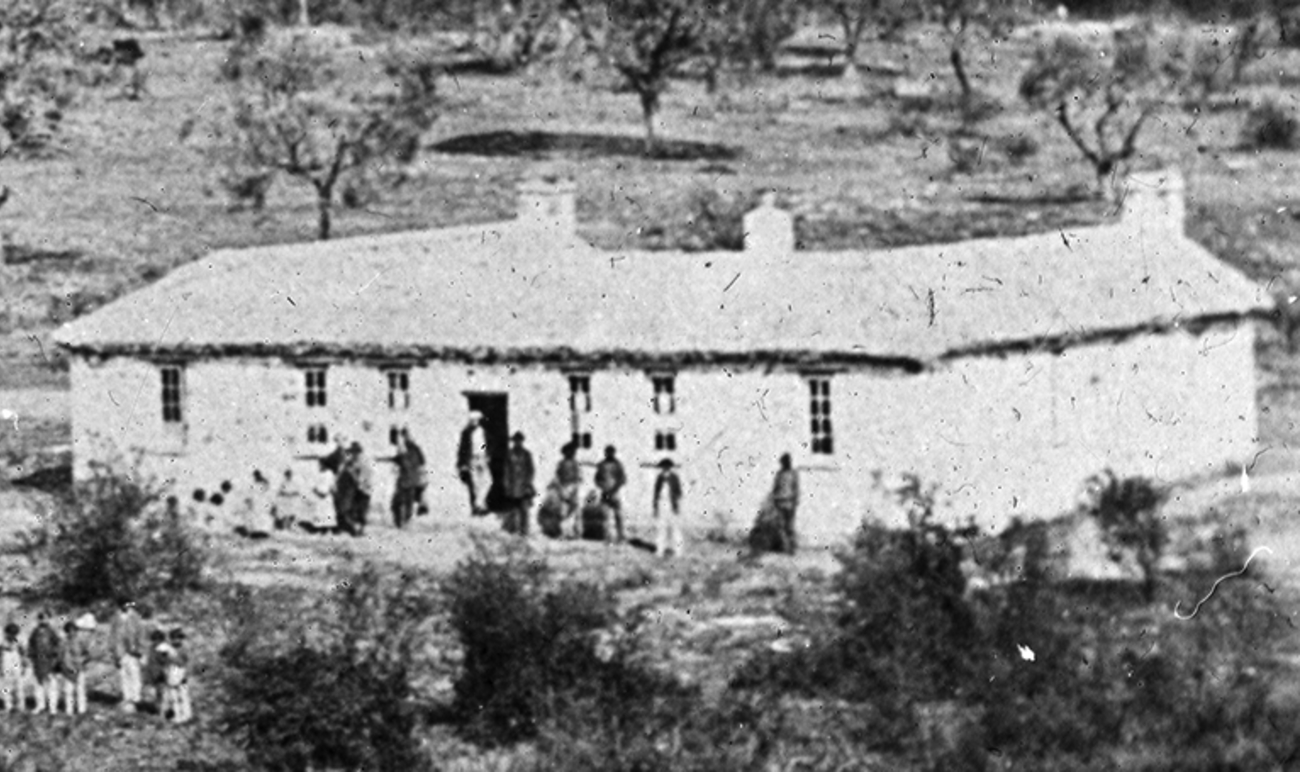

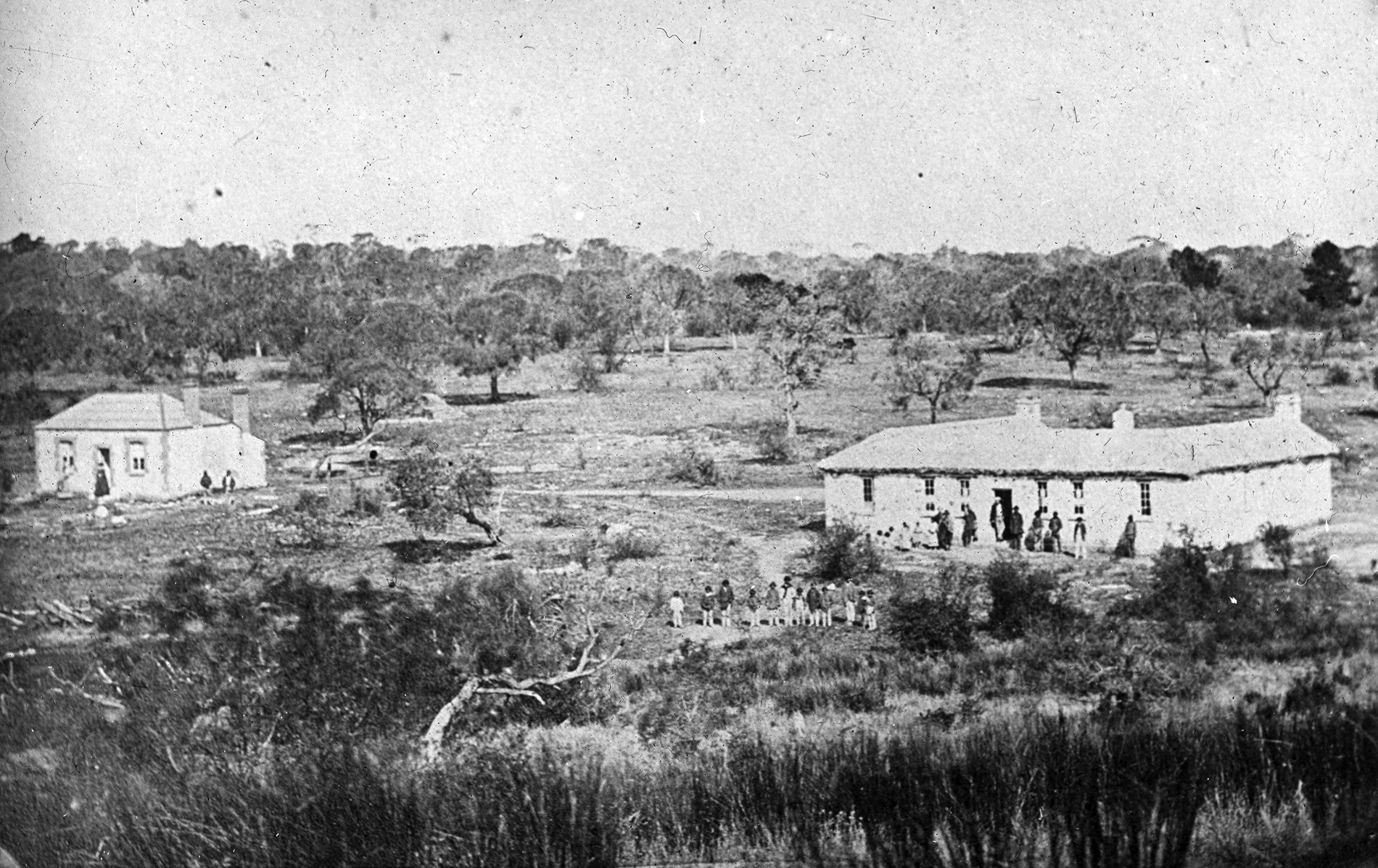

The Point Mcleay mission became home to many Ngarrandjeri people including Unaipon’s parents, James Ngunaitponi and Nymbulda. Established by the Aborigines Friend Association (AFA) in 1859, it is here that Unaipon’s father begins life as a missionary and preacher.

The mission is also where Unaipon receives a Christian education. An education that for a young boy is at times terrifying: ‘The missionaries appeared to take an almost unctuous delight in talking of the blood of Jesus and the hymns were full of it. When these hymns were sung I would be overcome with a sense of guilt and terror and this was shared by my companions’.[1]

Point McLeay Mission, 1860. The mission included a school, church and community housing. Photograph by Herbert Read, AIATSIS Collection READ.H05.DF-D00025887.

Point McLeay Mission, 1860. The mission included a school, church and community housing. Photograph by Herbert Read, AIATSIS Collection READ.H05.DF-D00025887.

Despite these childhood fears, Christianity would have a major influence on Unaipon’s life. He would later reflect that he owed much to his study of the bible and his father’s Christian example.[2] The AFA would also become an enduring employer, funding his trips throughout South Australia and Victoria in the 1920s.

But, we have skipped ahead in our story.

Let’s return to the mission and to the $50 note. But, we will need to look at an earlier note, one, that if you look to Unaipon’s right, you will see a set of drawings.

The brilliant inventor

While the mission was dedicated to raising Christian children, it also provided an opportunity for Unaipon to explore other interests. The AFA established a Mutual Improvement Society and offered mission residents lessons in music and drawing.

Unaipon’s musical brilliance was quick to shine. He played the church organ for a number of years and became a master of Handel’s ‘The Messiah’ and other complex refrains.[3]

The mission also had books and journals and Unaipon spent many hours poring over the pages of the scientific works. He became intrigued by the idea of perpetual motion and this would dominate his thoughts for much of his life.

Drawing on the way that boomerangs spin through the air, Unaipon developed plans for a flying machine that used spinning blades allowing it to rise straight up; much like the modern day helicopter.

He also studied the machine used in sheep-shearing and designed a modified handpiece. He was able to take out a provisional patent on the idea but couldn’t afford to get it fully protected. His design was later adopted. But, apart from a 1910 newspaper report acknowledging him as the inventor, he received no credit or financial reward.

During his life he would take out provisional patents for 19 inventions. Sadly, he was never able to afford to take out a full patent on any of them. Decades later his sheep shearing design would be inscribed on the $50 note.

If you take a closer look at that note, below Unaipon’s shearing tool design, you might also see some tiny print. For those of you with exceptionally good eyesight you might also be able to make out the words which read: ‘As a full-blooded member of my race I think I may claim to be the first — but I hope, not the last — to produce an enduring record of our customs, beliefs and imaginings’.[4]

They are words that Unaipon penned in 1924–25 as a preface to his manuscript Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. A manuscript that would not be published under his name until eighty years later.

The brilliant orator and writer

It is clear that Unaipon had an unquenchable thirst for knowledge. His was an inventive mind that expressed itself in many creative ways. He was also a practical man and was committed to bringing about positive change for Aboriginal people.

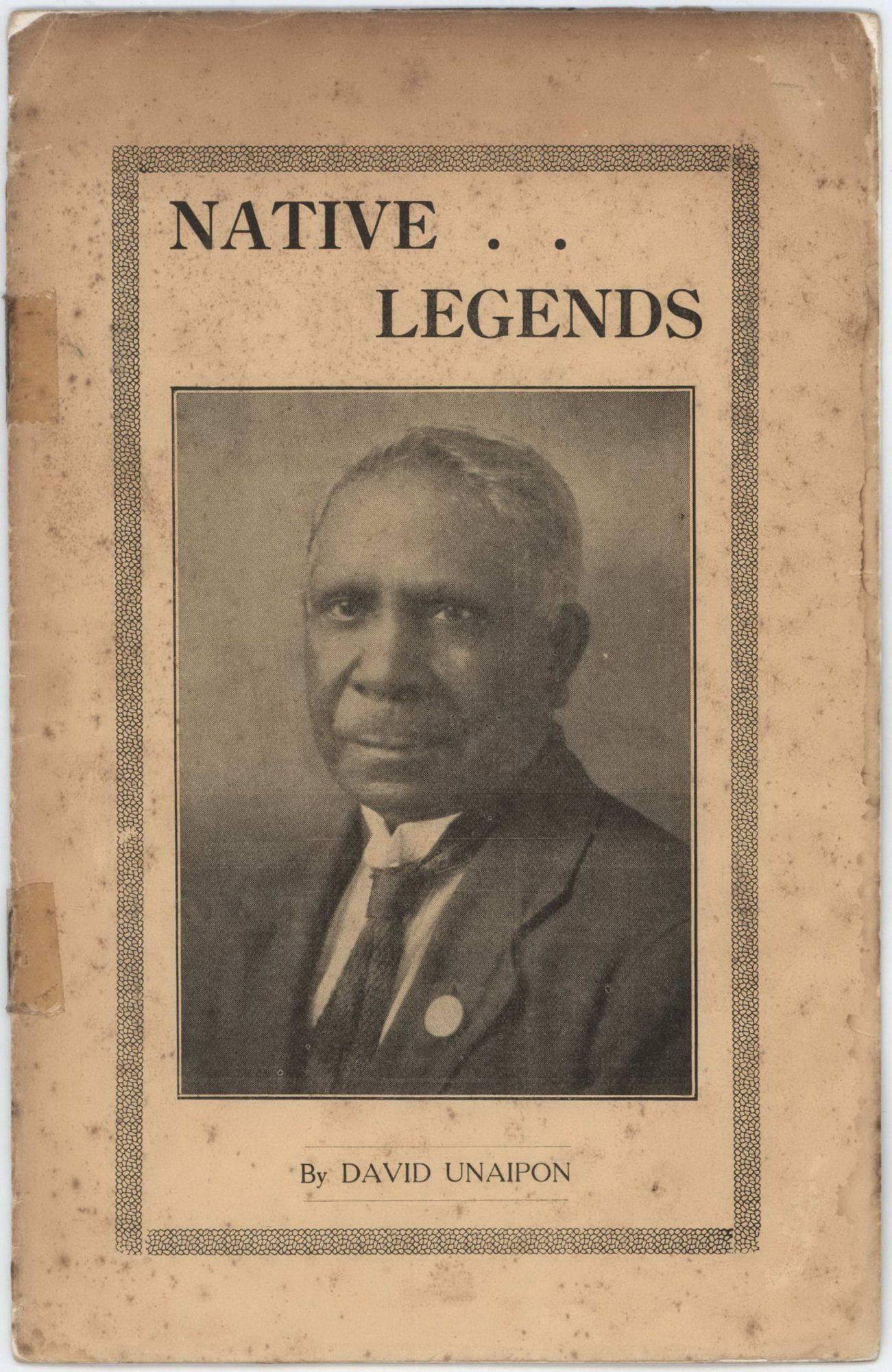

Throughout the 1920s he travelled around South Australia and Victoria delivering lectures and sermons at churches and schools. His travels were funded by the AFA and he collected subscriptions on their behalf selling thousands of booklets including his own work. Among these was his book Native Legends published in 1929.

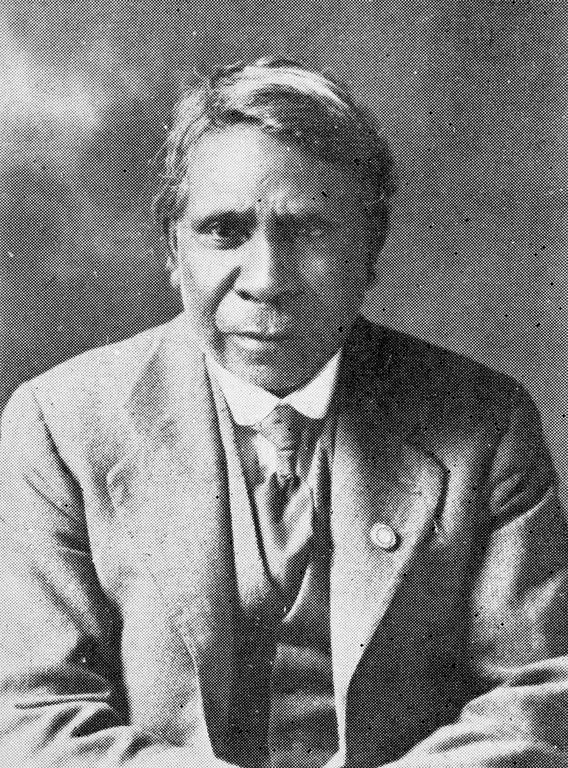

David Unaipon, South Australia, 1920s. AIATSIS Collection, JACKOMOS.A06.BW-N04416_31A.

David Unaipon, South Australia, 1920s. AIATSIS Collection, JACKOMOS.A06.BW-N04416_31A.

It was while he was travelling through southern Australia that Unaipon started to compile a collection of stories about Aboriginal cultures and customs.

In the mid-1950s he was commissioned by the University of Adelaide to assemble a book on Indigenous Australian stories. Incredibly his manuscript was later published with edits and without any attribution to him! Instead, the work appeared under the name of William Ramsay Smith who had purchased the manuscript from the publisher.

This wrong was finally made right in 2006 when Melbourne University Press published the work under Unaipon’s name as Legendary tales of the Australian Aborigines.

Unaipon had spent a considerable amount of time in the South Australian museum in the late 1880s studying his own and other cultures. His writings in Legandary tales of the Australian Aborigines reflect his broad study.

His stories are varied and rich with detail, navigating the routine and the ritual. Chronicles about everyday activities such as hunting and sport are interspersed with stories about marriage customs and Creation.

His writings also reveal a man that used his craft to alert and educate White Australia. In his 1934 ‘A Blackfellow’s appeal to white Australia concerning Chrisitian missions’ he writes:

‘My fellow Australians with white skins. I belong to a race in whose welfare you have lately been taking an unusually acute interest. I do not question the genuineness of your motives. Your sincerity is undoubted. But when I read your newspapers and the opinions of your politicians, missionaries and scientists, I am saddened and astonished at your ignorance of our problems. It is not us, it seems, who are most in need of enlightenment. You appear to know no more about us than if we were Tierra del Fuegans!’[5]

Unaipon was a master of the English language and a gifted writer. He is today celebrated as the first Australian Aboriginal author to be published in English. In 1988, the David Unaipon Literary Award was established in recognition of his talents.

Unaipon was undoubtedly a brilliant Australian. His flashes of brightness flicker long after his passing. His wisdom and passion to educate himself and others was profound. He was a thinker, driven to make a difference to the lives of Aboriginal people. Let us not forget the brilliance of the man on the fifty dollar note.

Further reading

Unaipon wrote numerous articles in newspapers and magazines including the Sydney Daily Telegraph and Dawn magazine. His stories in Dawn have been digitised by AIATSIS and can be viewed online:

- Why all the animals peck at the selfish owl, Dawn, 1955, v.4, no.4;16-17

- Love story of the two sisters, Dawn, 1959, v.8, no.9;19

- The voice of the great spirit, Dawn, 1959, v.8, no.8;19

- Why frogs jump into the water: an Australian Aboriginal legend, Dawn, 1959, v.8, no.7;17

References

[1] Unaipon D, 1951 ‘My life story’, Aborigines Friends Association, Melbourne, p. 3. p 016379.

[2] Ibid.

[4] Unaipon D, 1924-25, Legendary tales of the Australian Aborigines, S Muecke & A Shoemaker (eds), Melbourne University Press, 2001.

[5] Unaipon D, 1934 ‘A Blackfellow’s appeal to white Australia concerning Christian missions’ Pandemonium (Melbourne, Vic.) volume 1 number 5, p. 1.