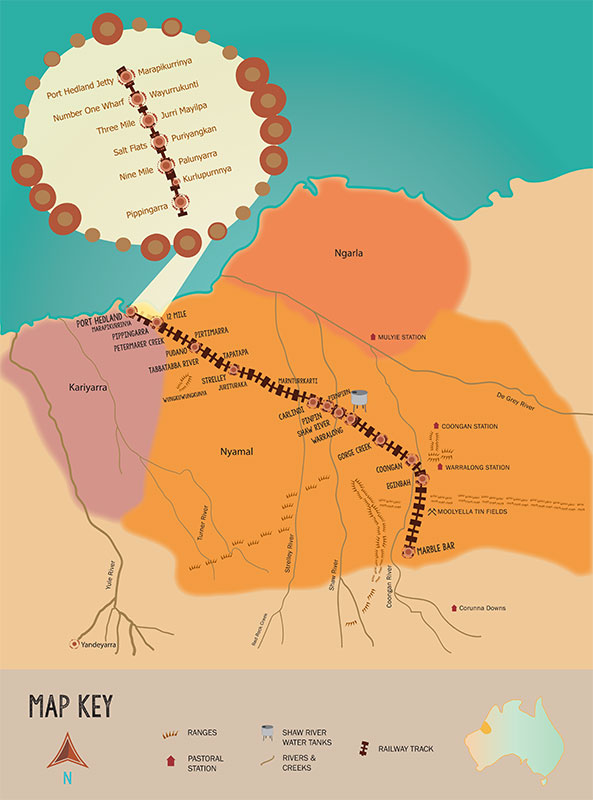

Songs like the Nyamal song, performed by Topsy Fazeldine about the Pilbara steam train that ran between Marble Bar and Port Hedland between 1911 and 1951, connect recent histories and experiences to ancient song styles.

The Nyamal train song is known as a Japi song, a public song that was composed by Pilbara stockman Mangkayipirti or Larry Brown. It tells of the sights and sounds of the train’s journey through Nyamal country.

Larry Brown, whose Aboriginal name is Mangkayipirti, was born toward the end of the nineteenth century, around 1895, near Mulyie pastoral station. Mulyie was one of the earliest sheep stations in the Pilbara, situated on the De Grey River. Larry Brown was one of the early generations of pastoral workers in the area and worked as a stockman on or near Mulyie until his death in 1950. He was buried one mile from Mulyie station homestead. Larry’s Paddock at Mulyie is believed to be named after him.

In 1964, Mangkayipirti's daughter Topsy Fazeldine (Marrparingu), recorded the Nyamal train song with visiting language researcher Carl Von Brandenstein.

‘Nyamal song I’m going to sing train my father’s song…singing train from Port Hedland to Marble Bar.’ — Topsy Fazeldine (Marrparingu)

Basil Snook gives permission for this 1964 recording of his mother to be made public. Listen to the train song and Basil’s introduction.

Topsy Fazeldine was born in 1922 near Mulyie pastoral station. She worked as a domestic and stock camp assistant at Mulyie station and stations along the De Grey River and the train line. In about 1946 she joined the Pilbara pastoral strikers at Twelve Mile camp outside Port Hedland and travelled with them to the tin mining enterprise at Moolyella. She worked on stations occasionally through the 1960s, but was mostly travelling with her husband Mick Fazeldine through towns and various camps from Port Hedland to Marble Bar. Topsy Fazeldine died in 1991.

Topsy Fazeldine with her daughter Shirley photographed in 1984 when she recorded the train song. AIATSIS Collection, Von Brandenstein C03.CS-000169588.

Topsy Fazeldine with her daughter Shirley photographed in 1984 when she recorded the train song. AIATSIS Collection, Von Brandenstein C03.CS-000169588.

The Train Song is about a recent event. It is also inextricably linked to community life, language and country and the long histories of Aboriginal people in the Pilbara. To sing this Japi song is to sing a journey through country. Calling the country place by place brings it back to life and ensures it continues. Mangkayipirti created a song that told of the journey through his country singing and calling the Nyamal names of hills, waterholes and places of significance. He passed this song to his daughter Topsy Fazeldine, who recreates the journey through the song and keeps her culture alive.

The recording of the Nyamal train song was archived at AIATSIS. Fifty years later in 2014, Topsy’s son Basil Snook and Elders from the Nyamal community heard the old recording of the train song and began their own journey of finding the old train tracks. They translated the song into English and put it into film and an exhibition to share it with everyone, especially young Aboriginal people of the Pilbara.

Nyamal Elders worked with AIATSIS, Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre in Port Hedland and Revolutions Transport Museum in Perth to create the Singing the Train Song exhibition and films, launched at AIATSIS in Canberra in November 2016.

‘It’s not just a song but it’s this whole journey, through culture, through time, connecting people.’ — Talor Derschow

Elders and storytellers return to the track

‘Ngaja ngaany wanpari (It makes me feel good in my heart)’ — Alice Mitchell

Nyamal Elders Alice Mitchell and Jane Taylor were looking for a language project to support and encourage the use of Nyamal. Julie Walker, manager at Wangka Maya explains: ‘Nyamal is one of those languages that is endangered so it’s really important that we do projects to keep it alive. Our Nyamal Elders and language speakers Alice Mitchell, Jane Taylor and Teena Taylor have worked on the train song with Basil Snook’s support because he is a custodian for his grandfather’s song.’

Alice, Teena and Jane worked with AIATSIS researchers to translate and transcribe the train song and record their memories of catching the train. As part of this process, Elders Alice Mitchell, Bruce Thomas, Ron Walker, Nora Cooke and Basil Snook led trips to country to find what remains of the old train tracks. On one trip, they located old tracks in a dry river bed outside of Marble Bar, and on a later trip Bruce Thomas found remains of the track at Puntanya, near the old Pudano siding.

While on country the Elders shared their memories of riding the train. The train often stopped for people along the line, even if they weren’t at a siding. Aboriginal storytellers remembered hardly ever paying to ride; they had few coins anyway as they were mostly unwaged station workers paid in rations.

Aboriginal people also rode the train to meet up for ceremonial gatherings, to go to hospital or to go to Moolyella to prospect for tin. Teena Taylor remembers: “When I was small I learned to yandy, in those days, no money. You gotta work hard. We got tin, these little bits, like that’s money.’

Nora Cooke remembered a story her mother loved to tell about the train: ‘When my mum was a little girl about 8 years old... they were going from the Carlindi homestead to the Carlindi Siding and they saw this light coming. So the two old girls said “Run! Run to stop the train” So the two little girls they was running and running and then they looked and found out that it was the moon coming up so they had a good laugh… it was only the moon coming up!’

Japi Songs

The Nyamal train song is a Japi song composed by an individual about everyday things that were witnessed or experienced in recent times. Japi songs are public songs for anyone to listen to. They are also known in the Pilbara as Nyirlpu and Yirraru. Japi songs are often about travelling, and the experiences of riding, seeing and hearing machines like trains, planes, trucks and boats, and even a washing machine.

Japi songs are often accompanied by rhythmic scraping sounds created by rubbing a hard instrument like a rock or coin across a rough surface. Some singers created special wooden instruments by cutting notches into a boomerang or solid piece of wood and rubbing a thinner stick along it. Topsy Fazeldine sometimes used a coin on an old washboard. Bruce Thomas remembers the singers rubbing a coin on the top of an old tobacco tin to create the rhythmic sound. Guitars are also occasionally used in the same way as the tobacco tin or an old tin can.

The boat song

The composer of the train song, Mangkayipirti (Larry Brown) also composed a boat song. His daughter Topsy Fazeldine recorded the boat song in 1961 when amateur folklorist Ian Conochie sat with her at One Mile camp just outside Port Hedland. The boat song tells of a ship churning the water with its engines as it battles the winds of a cyclone. Nyamal Elder Alice Mitchell also sings a Japi boat song, ‘Kulinta’ about the State ship Koolinda.

Artists renewing the song

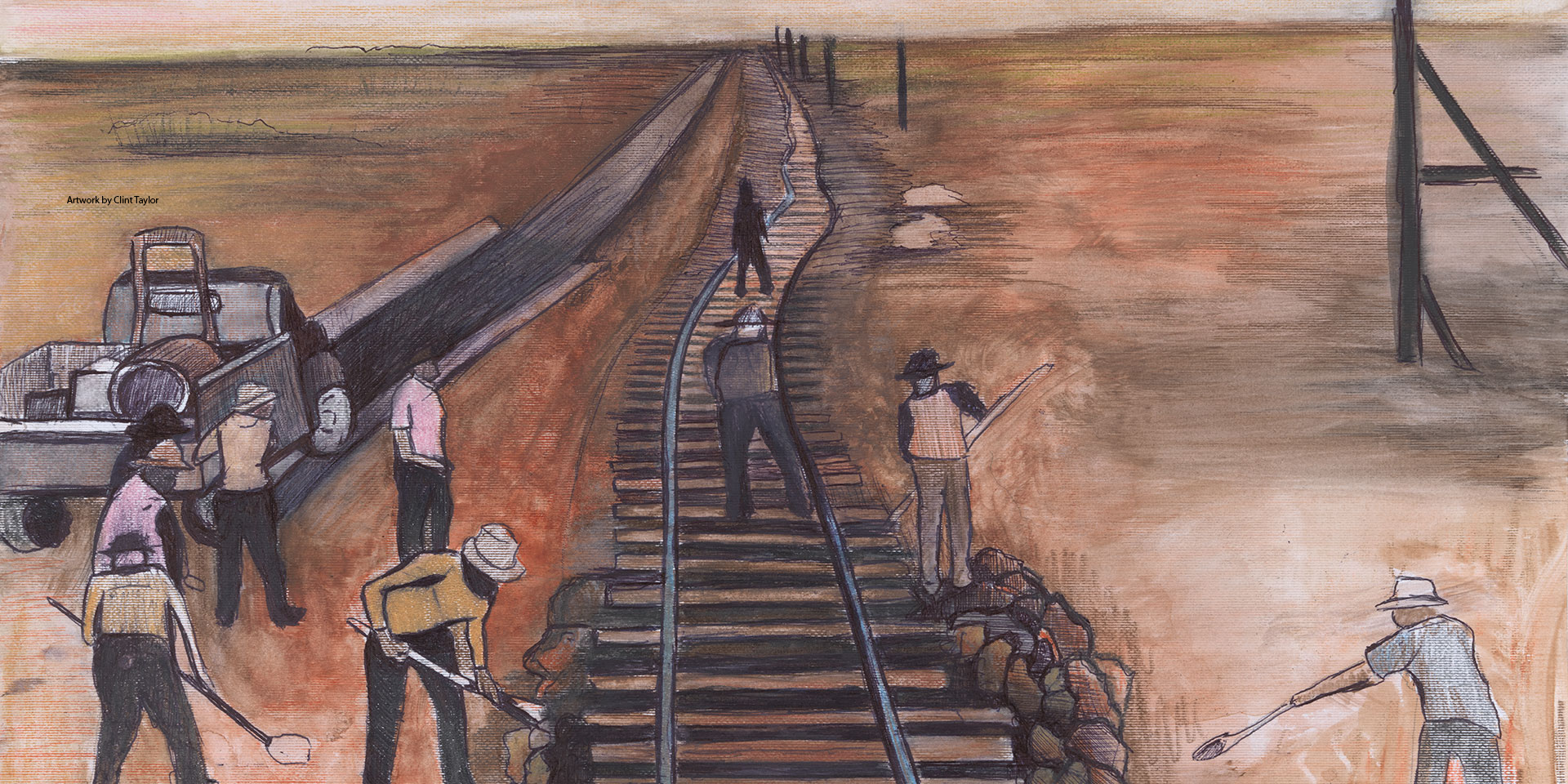

‘I think art tells us stories and is a great resource to educate people, when you don’t have the right words to say something, it’s there to be expressive.’ — Clint Taylor

‘I create images to help bring a sense of connection between the audience and our language work.’ — Talor Derschow

Two young Pilbara artists, Clint Taylor and Talor Derschow, were commissioned to develop their interpretation of the train song for an exhibition at AIATSIS.

Clint has worked as an illustrator at Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre for several years. Illustrations are an important part of the Wangka Maya language material, providing visual assistance for language learning.

Clint is a watercolour artist who uses shading and layers to develop colour and provide depth. He describes his art as ‘surreal, dreamlike’. Clint has developed a unique interpretation of colour; ‘the colours are kind of different. … I think people miss seeing the beauty in colours sometimes and I think that’s what I try and capture because to people a red colour is just red, but there’s so much more colour in that red that people do not see.’

Clint Taylor talks about his work as an artist.

Talor is a Banyjima and Nyangumarta artist from Port Hedland. She has worked as an illustrator at Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre, creating visual aids for language publications. Talor creates art digitally. She uses an electronic drawing pad and illustrating software to develop her distinct and evocative images.

For Talor, multimedia projects such as the Singing the Train ‘not only preserve and help protect our heritage and our culture but also show the wider public that we are still here. We still exist and we are still important to the country.’

History Matters

By publishing these stories online, Nyamal Elders and Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre are ensuring that Pilbara Aboriginal culture and languages continue to be heard and respected. They also wanted to let people know that all Aboriginal people of the region have struggled to speak out and to keep their language and culture strong. Despite a history of invasion, a violent frontier and massive recent dislocation through mining, songs like the train song have kept culture alive.

The story of the Spinifex Express

Pilbara history is a long and deep history, with rock artworks, song cycles and culture that are thousands of years old. Aboriginal people of the Pilbara experienced enormous changes to their culture from the 1870s and 1880s when European pastoral and mining industries invaded their land. From the 1960s to recent years, mining development changed the landscape and caused huge disruption to Aboriginal peoples’ lives. Throughout these times government policies disempowered Aboriginal people by limiting their chances to continue to control and manage their land in ways that had existed for generations.

While all communities suffered from the early years of a violent frontier, many Pilbara Aboriginal people managed to stay close to their land as part of the pastoral economy. In 1946 after the Second World War, Pilbara people carried out the first mass walk off of Aboriginal pastoral workers in Australian history, demanding better living conditions and wages. Many did not return and supported themselves through mining. Some Pilbara children like other Indigenous people of Australia, especially fair skinned children, were removed from their families and institutionalised. Their connection to their land and families was broken for generations.

Most Pilbara Aboriginal people went to camp on town reserves, worked occasionally for pastoral stations or as domestics and continued to live in the region. On the reserves and on the stations people composed and shared Japi songs. However Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara, and Japi songs are under threat. Nyamal language is spoken fluently by only a small number of people and is considered endangered. Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre Board and AIATSIS encourage projects like the Train Song exhibition to help keep language and culture alive. The Nyamal train song is also vitally important as it is allows Aboriginal people to reclaim their right to tell the true history of the Pilbara.

Acknowledgments

The Singing the Train project is a collaboration between Nyamal Elders, AIATSIS, Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre and Revolutions Transport Museum. Thank you to the Elders for sharing their knowledge and stories.

Thank you also to the Pilbara artists, Talor Derschow and Clint Taylor, whose illustrations have been used for these exhibitions. The artists are represented by Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre in Port Hedland, Western Australia.

The material in this exhibition is not to be copied or reproduced without the permission of the Nyamal Elders.

The following organisations are acknowledged for the use of their resources throughout this project:

- Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Revolutions Transport Museum of Western Australia

- National Library of Australia

- State Library of Western Australia

- Rail Heritage WA

- Royal Western Australian Historical Society Inc.

- State Records Office of Western Australia

- Conochie family

This online story was curated by AIATSIS researchers Mary Anne Jebb and Nell Reidy and is a resource shared by the collaborating partners and cultural custodians.

Recording and keeping the song

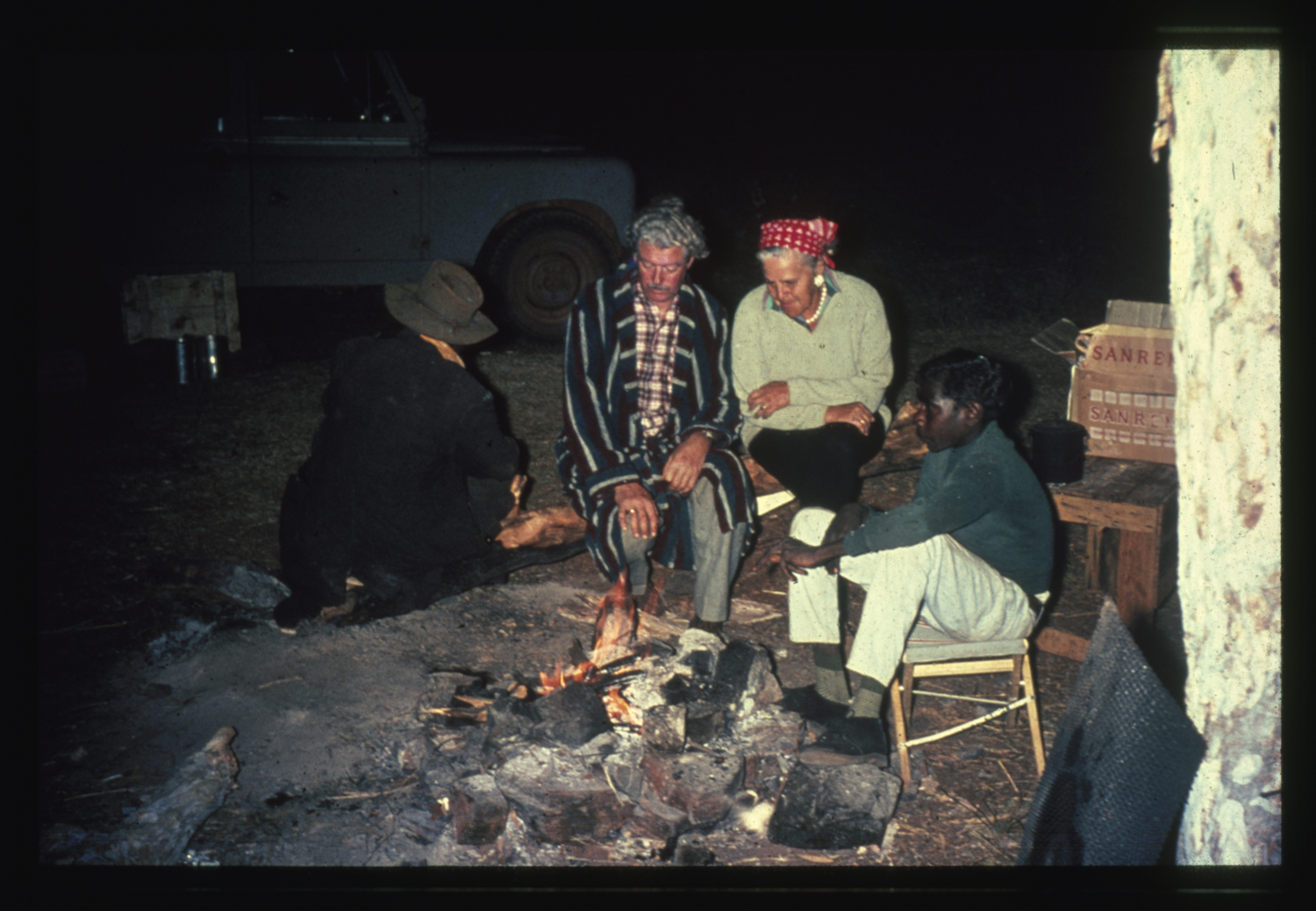

Carl von Brandenstein was born in Hanover, Germany in 1909 and studied languages at Berlin University. At the outbreak of the Second World War, von Brandenstein became a corporal in the German Army and was captured by the British in Persia in 1941. He was interned as an enemy alien in South Australia and later Victoria and when the war ended, von Brandenstein stayed in Australia. He was one of the earliest recipients of an Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (later AIATSIS) language and anthropology research grant.

Between 1964 and 1967 he made recordings of Aboriginal oral histories and songs in town camps and on stations across the Pilbara and northwest of Western Australia. In 1964 he recorded Topsy Fazeldine (Marrparingu) singing the train song. Von Brandenstein’s collection at AIATSIS includes some slides that were taken when he recorded Aboriginal languages and songs. There is ongoing work to repatriate digital copies to families and communities and to better identify the people and places in these images.

Von Brandenstein used a Butoba tape recorder which recorded onto reel to reel magnetic tapes. These tapes have been digitised and today, von Brandenstein’s recordings are an important part of the AIATSIS collection.

Cameron Burns, Senior Audio Technician at AIATSIS talks about the preservation of the Von Brandenstein recordings.

Digitisation of analogue material is critical because magnetic media, such as the von Brandenstein audio tapes, is under threat of chemical decomposition, the equipment needed to replay the material is no longer manufactured, and the expertise needed to maintain this equipment is rare.

Most importantly however, digitisation allows for the return of material to family and communities, and easier access in a digital world.