Early years

Born on 29 June 1936 in his village of Las on the island of Mer in the Torres Strait, Eddie Koiki Mabo was the fourth child of Robert Zesou Sambo and Poipe (Sambo) Mabo. His mother passed away shortly after his birth and he was adopted by his Uncle Benny and Aunty Maigo Mabo in line with Islander custom.

Koiko’s first language was Meriam and he grew up immersed in his Meriam culture. He was taught from a young age about the importance of respecting other people’s land. These strong cultural roots would be the basis for his later legal challenge.

In 1959 he moved to Townsville in Queensland and held a variety of jobs including working on pearling boats, cutting cane and as a railway fettler. In the same year he married Bonita Neehow, an Australian-born South Sea Islander, and together they had ten children.

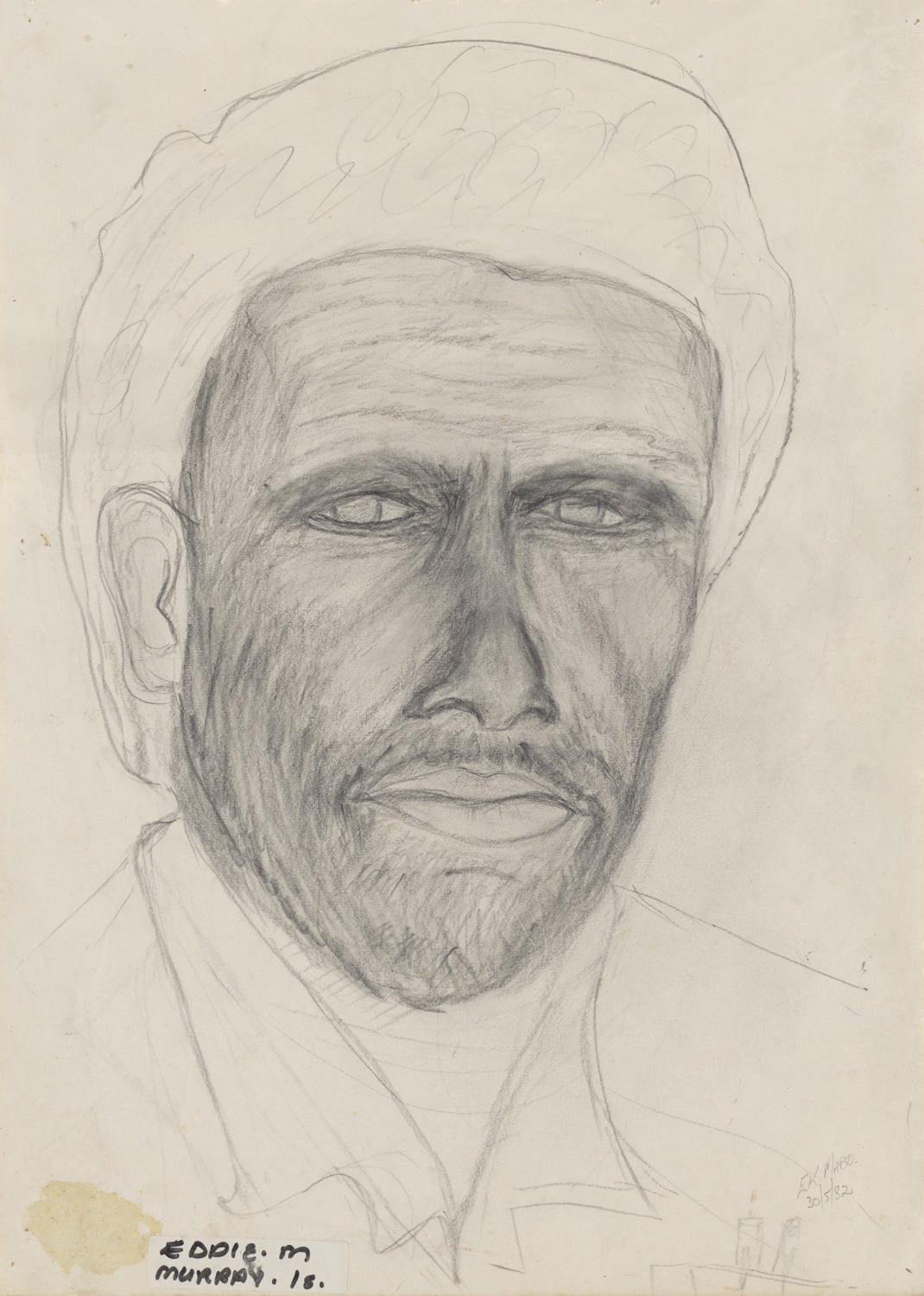

Koiki was a skilled performer and teacher of Meriam song and dance. He also enjoyed art and spent his spare time painting water colours and relaxing on his boat. A number of his artworks are in the AIATSIS collection including this unique self-portrait that he drew in 1982.

Meriam way

While most of his adult life was spent on mainland Australia, Koiki’s cultural identity remained deeply rooted in Malo law and Meriam custom.

When he was about fifteen years old, he recalled ‘spending four weeks receiving instructions on the laws of Malo and how they should be applied; about behaviour towards other males and towards women, how to tend gardens, the right season to plant and the signs to watch.1

He described how his grandfather had told him that after the missionaries arrived, the men continued to participate in Malo initiation ceremonies in secret. That when Mabo himself was nine or ten years old, he was taken with other boys to learn dances and songs such as that of Gelam, who formed the isle of Mer in the shape of a dugong, and the history of Malo.2 This would become an important story in Koiki Mabo’s landmark legal case.

A life of campaigning

Koiki quickly involved himself in politics and community organisations, becoming a prominent leader for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Queensland. He served on many boards including as President of the Council for the Rights of Indigenous People. He was also involved in the 1967 Referendum campaign to have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples included in the census and to allow the national Australian Government, rather than the state and territory governments, to make laws that affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

His village Las would always remain his home. Sadly, he would later be denied the right to return to his homelands because of his active campaigning.

One of Koiki and Bonita’s daughters, Gail Mabo, recalls:

‘In 1972 my family had planned to visit Mer. My father had hoped to visit his father, Benny Mabo, who was suffering from tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was a major killer of Torres Strait Islanders at the time. Our family travelled to Thursday Island but we were refused permission to travel to Mer.'

‘My mother, Bonita, remembers:

“In those days you had to get permission to go across to Mer, but the Queensland authorities wouldn’t let us. They said Eddie was a non-Islander, because he hadn’t lived there for so long. They thought he was too political and would stir up trouble.”

‘Our family returned to Townsville. Six weeks later my father received a telegram saying that his father had died. My father cried. We never had the chance to meet our grandfather.

‘My father never forgave the government authorities for this injustice. It fuelled his determination for recognition and equality in society. This began his ten-year battle for justice and political status.’

The black community school

In 1973, Koiki became co-founder and director of the Townsville black community school — one of the first in Australia. Unhappy with the approach to Indigenous education within the Queensland state education system, Koiki volunteered to work for half pay to help establish the school.

The Black community school in Townsville, November 1981. Photograph by Anna Shnukal, AIATSIS Collection, SHNUKAL.A01.CS-000071831.

The Black community school in Townsville, November 1981. Photograph by Anna Shnukal, AIATSIS Collection, SHNUKAL.A01.CS-000071831.

The school started with ten students in an old Catholic school building in the heart of inner city Townsville. It was regarded with open hostility within the general Townsville community including the Queensland Education Department, local newspaper and some local politicians. The then State Minister for Education denounced the motives of the student’s parents declaring their attitudes as racist and the school as ‘apartheid in reverse’.

At its peak in the late 1970s, forty five students were enrolled at the school. In 1975, Koiki was asked to join the National Aboriginal Education Committee (NAEC), an advisory body to the Commonwealth Education Department which he served on for three years. Always active in defense of Torres Strait Islander rights, he also chaired the Torres Strait Border Action Committee in Townsville.

Eddie Koiki Mabo in Townsville, 1991. Photograph by Bethyl Mabo, AIATSIS Collection, ATSIC.002.BW-E00256_31.

Eddie Koiki Mabo in Townsville, 1991. Photograph by Bethyl Mabo, AIATSIS Collection, ATSIC.002.BW-E00256_31.

A turning point

A turning point in Koiki’s life happened while he was working on campus as a gardener at James Cook University. University historians Noel Loos and Henry Reynolds recall:

‘...we were having lunch one day when Koiki was just speaking about his land back on Mer, or Murray Island. Henry and I realised that in his mind he thought he owned that land, so we sort of glanced at each other, and then had the difficult responsibility of telling him that he didn't own that land, and that it was Crown land. Koiki was surprised, shocked... he said and I remember him saying, 'No way, it's not theirs, it’s ours!'

Koiki went on to give a speech at a land rights conference at the university explaining the traditional land ownership and inheritance system that his community followed on Mer. A lawyer in the audience noted the significance of Koiki’s speech and suggested there should be a test case to claim land rights through the court system.

The Mabo Case

Perth based solicitor Greg McIntyre agreed to represent Mabo and recruited barristers, the late Ron Castan and Bryan Keon-Cohen. Greg McIntyre and Koiki both applied successfully for research grants from AIATSIS to conduct research for the case.

On 20 May 1982, Koiki and fellow Mer Islanders, Reverend David Passi, Celuia Mapo Salee, Sam Passi and James Rice began their legal claim in the High Court of Australia for ownership of their lands on the island of Mer. With Koiki as the first named plaintiff, the case became known as the ‘Mabo Case’.

As part of his testimony during the case he explained how his grandfather had taken him to the village of Las and shown him his land boundaries and his fish traps. His grandfather explained how meriba ged, or our land, came to be handed down through five generations to his father. His grandfather told him, ‘If your father will get old you will take his land like he did when I get old’.3

On 21 January 1992, nearly ten years after beginning their legal claim in the High Court of Australia, Eddie Koiki Mabo passed away from cancer aged fifty-six.

On 3 June 1992, the High Court of Australia decided in favour of Eddie Koiki Mabo and his fellow plaintiffs. The ruling on this landmark case recognised in Australian law for the first time the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to their lands based on their traditional connection to and occupation of their Country; a decision that countered the claim by the British that Australia was ‘terra nullius’ (land belonging to no-one).

The following year the Parliament of Australia passed the Native Title Act 1993 to create a system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to make a native title claim over their lands.

Awards and recognition

Eddie Koiki Mabo has been rightfully recognised for his landmark work. Unfortunately this recognition only occurred after his death.

- 1992: awarded the Australian Human Rights Medal along with his fellow plaintiffs ‘in recognition of their long and determined battle to gain justice for their people’.

- 1993: voted as Australian of the Year 1992 by the Australian newspaper (not to be confused with the Australian Government’s Australian of the Year Awards).

- 2008: James Cook University library was named in his honour.

- 2012: the Australian Broadcasting Corporation aired Mabo: the movie, a documentary drama based on his life.

- Mabo day: Celebrated on 3 June each year to commemorate his courageous efforts to overturn the fiction of terra nullius.

- Mabo lecture: An annual lecture held as part of the AIATSIS National Native Title Conference.

Further reading and sources

References