Note that some of the language in archival sources reflects the language used at the time and may cause offense. AIATSIS does not condone the use of this language.

The world first learned of the Torres Strait Islanders’ defiant stand in 1936 when news of their historic maritime strike rippled across the nation’s newspapers.

It was January 1936, pick-up time for 400 ‘Company Boat’ men, as Protector J.D. McLean moved from island to island signing crews for boats owned by Torres Strait Islanders but controlled by the Protectors. The fleet of luggers and cutters lay silent at anchor, their sails furled, as if holding their breath against the tide of change.

Setting the Scene

Torres Strait Islanders (Eastern Meriam, Central Kulkulgal, Western Maluilgal, Top Western Guda Maluilgal) have maritime economies, deep ritual and voyaging traditions refined over millenia that continue to the present time.3

From bipotaim4 to the present, deep knowledge is marked by the seasons and embedded in stories, songs and lived experiences.

Torres Strait Islanders have long stood at the forefront of the fight for justice and rights—leading movements that shaped the future for First Nations peoples across Australia. The 1936 Torres Strait Maritime Strike would become the first in Australia to be led by First Nations people.

The 1936 Torres Strait Islander strike didn’t happen overnight—it was the breaking point of decades of simmering tensions. Behind the fight for rights by pearl lugger workers lay a web of long-standing injustices and systemic pressures that finally boiled over.

By 1879, the British Colony of Queensland5 dramatically expanded its reach into the Torres Strait by passing the Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879, pushing its maritime boundary from 3 miles (4.8 kms) to 60 miles (96 kms) offshore. The colony wanted control over the Torres Strait’s booming pearling and bêche-de-mer6 industries and its sea lanes.7 The Act enabled the Queensland Colony to control and regulate these industries, which had previously operated outside its jurisdiction.8

Queensland’s annexation of the Torres Strait Islands placed Torres Strait Islanders under colonial rule, dismantled their own governance structures, and imposed restrictions on movement and employment.

It entrenched terra nullius, denying land rights until the landmark Mabo case in 1992 restored native title on Mer / Murray Island.

In 1897, the Queensland Colony enacted the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (the 1897 Act). Enforcement in the Torres Strait was overseen by Government Resident and Police Magistrate of Waibene / Thursday Island, the Honourable John Douglas (appointed in 1885). His approach was ‘paternalistic, benevolent and autocratic’.9 Douglas’ writings and decisions suggest respect for Torres Strait Islanders’ capacity and a belief that they should be shielded from exploitation, but within firm colonial bounds. He promoted local councils and island leadership by mamus / mamoose10 under government oversight, reflecting confidence in community authority—so long as it harmonised with colonial order.11

Douglas opposed classifying Torres Strait Islanders under the 1897 Act, effectively buffering the Torres Strait from Queensland’s most intrusive controls.12

In 1901, Queensland became the sixth state of the Commonwealth of Australia. Torres Strait Islanders were excluded from the census13 and Commonwealth powers.

Following John Douglas’ death in 1904, the Chief Protector’s authority was extended to the Torres Strait, and Torres Strait Islanders were brought under the 1897 Act’s machinery—restrictions on movement, wage controls, residence on reserves, permits, and moral regulation—ushering in a period widely remembered by Torres Strait Islanders as the start of the protectionist era.14

Sharing the deeply personal impact of coming under the Chief Protector’s control, Wees Nawia, Chairman of Moa / Mua Island recalled the heartbreak of being uprooted—his family taken from their home on Kirriri / Hammond Island and moved to Moa, a separation that left lasting impacts:

‘…I grew up at Hammond Island until 1914 war. When I came to age about eighteen here comes an order from the Chief Protector Mr Bleakley. He sent a man out to Hammond Island and tell all these people to get away from Hammond Island to Moa Island. Oh terrible! I saw my uncle that brave, just go and push all those white people who come out with revolvers. He was something like a giant, a strong-hearted man. I was frightened they might shoot my uncle. So the police said, ‘You jump in the dinghy you cheeky boy,’ and put a revolver to my chest and pushed me into the dinghy. The mothers and sisters all cry and go and take all their things and Badu and Moa people made grass houses at Poid, Moa. It was oh, big cry that night. Moa people come and the Hammond people cry and the Moa people they didn’t like us to have to leave Hammond. I don’t know why they moved us’.15

Company Boats versus Master Boats

In response to a request by Torres Strait Islanders who wished to own their own boats, Company Boats were introduced in 1904 by the Rev. F.W. Walker.

Company Boats were luggers owned and worked by Torres Strait Islanders but controlled by the Queensland Protector, who dictated crewing and handled earnings.

Master Boats, by contrast, were privately owned by European and Japanese owners, typically paying higher wages and recruiting seasoned crews outside the Protector’s direct oversight.

Rev Walker, a former London Missionary Society (LMS) missionary, founded Papuan Industries Limited (PIL), a Christian trading station at Badu / Mulgrave Island to support Torres Strait Islander economic self-reliance16.

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N04034_06, Bringing pearl shell ashore from dinghies, beach in front of Burns Philp, wharf in distance, William MacFarlane, Waibene/Thursday Island, 1932, AIATSIS Collection.

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N04034_06, Bringing pearl shell ashore from dinghies, beach in front of Burns Philp, wharf in distance, William MacFarlane, Waibene/Thursday Island, 1932, AIATSIS Collection.

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N04113_04, Group of men beside stack of pearlshell near the jetty, William H MacFarlane, Waibene/Thursday Island, 1930, AIATSIS Collection.

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N04113_04, Group of men beside stack of pearlshell near the jetty, William H MacFarlane, Waibene/Thursday Island, 1930, AIATSIS Collection.

‘By 1907 there were eighteen boats; half of them had been fully paid for with the interest by the Island owners.’17 It was a time when Torres Strait Islanders could compete with their former employers—the European-owned ‘Master Boats’ that had previously hired Torres Strait Islanders, Aboriginal people, and indentured Asian crews to work on their boats.

For the Protectors and the Administration (the state of Queensland), Torres Strait Islanders owning their own fishing boats was more than an economic shift—it was a bold claim to independence, a quiet rebellion that threatened the very control they sought to maintain.

A series of changes to PIL stripped Torres Strait Islanders of control over their ‘Company Boats,’ transferring authority to the Administration. The Protector took charge of crew recruitment and pearl shell sales shifted from open tender to compulsory sale to the Aboriginal Industries Board (AIB)—the renamed PIL, purchased by the Administration in 1930. Torres Strait Islanders’ earnings were fully controlled: part diverted to the Island Fund (established in 1912), the rest as store credit at AIB outlets. If the Protector judged a boat was not being worked ‘satisfactorily,’ it could be confiscated—further tightening the Administration’s grip.18

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N03964_01, William H MacFarlane, Papuan Industries boat shed (taken over by the Queensland Department of Native Affairs (DNA) in 1930), 1926, AIATSIS Collection.

MACFARLANE.W02.BW-N03964_01, William H MacFarlane, Papuan Industries boat shed (taken over by the Queensland Department of Native Affairs (DNA) in 1930), 1926, AIATSIS Collection.

CANE.F02.BW-N00077_25, Allan Cane, New dinghy [and tradesman at Aboriginal Industries] workshop on Badu, Queensland Attorney-General John Mullan's official tour of the Torres Strait Islands and far north Queensland, Badu, 1935, AIATSIS Collection.

CANE.F02.BW-N00077_25, Allan Cane, New dinghy [and tradesman at Aboriginal Industries] workshop on Badu, Queensland Attorney-General John Mullan's official tour of the Torres Strait Islands and far north Queensland, Badu, 1935, AIATSIS Collection.

Cast-iron rule came in the form of Protector JD McLean who was appointed local Protector in 1932. JD McLean increased restrictions over the lives of Torres Strait Islanders through increasing police surveillance, introducing curfews19, controlling all their earnings and removing individuals to Palm Island. McLean also removed elected Island Council representatives and appointed his own representatives.20

In 1934 changes were made to the Protection of Aboriginals and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Amendment Act 1934 (Protection Act 1934)21 that included defining descendants of South Sea Islanders as ‘natives’ and ‘half-castes’, extended powers of control over Torres Strait Islanders (including removals and confinement to institutions), and creation of the Aboriginal Industries Board (AIB) to regulate employment and economic activities.

In 1935, hopes of prosperity from a year of high prices were crushed when officials reclaimed debts from previous years – ‘we never knew where we were,’ said Marou Mimi, one of the strike leaders.

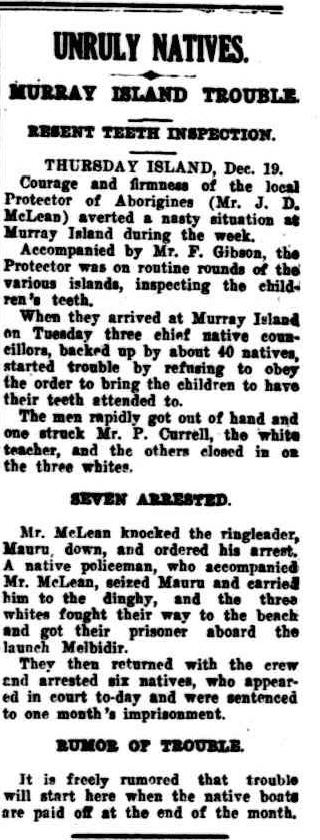

In December 1935, Chief Protector McLean hit Marou Mimi, the Mer / Murray Island Chief Councillor, and then sacked him. The incident was reported in the Cairns Post on 19 December 1935. In protest, Mer Islanders refused to elect Councillors until the authority of the Protector to dismiss Councillors was revoked.22

By the end of December 1935 several Company Boats gathered around a reef and plans were laid for a general strike in the new year24.

Badu man Nau Mabaig, tells how the message to strike was circulated around the islands:

‘In that time there was a cargo boat used to sail. It was a boat called Dargo (renamed Mulgrave) and the skipper was called ‘Old M’ (Mairu). When he goes to Murray Island the things they decided there they sent a message with him to bring up here…When he sails through Torres Strait, whichever Island he comes to yarn there with them. Cargo boat of Aboriginal Industries Board carrying cargo and taking message [laughter]. Carrying cargo and loading messages! When he calls at some of the islands like Central Islands, then come down to Badu, he let us hear the message on the island of Badu. Then, when he takes cargo to Saibai, Dauan and Boigu he takes the message and tells them.'25

Self-Determination in Action: Refusing to Crawl on Hands and Knees – The Strike

Meriam man Marou Mimi, a key figure in the 1936 strike, told historian Nonie Sharp the action was driven by a fight for self-determination and control over hard-earned wages.

‘For a long time the money was controlled by them. The money we earned had to be entered into a passbook and when you walked into the place they would say, ‘Oh, you have drawn money on Monday, you can’t have any more this week.’ So that was what the strike was about. Yet the money was ours; we battled to get it. We used to crawl on our knees and say, ‘Please, please, I would like more…’ If she said ‘no’ that was it. If we spent the money the wrong way, well that was up to the people themselves. We wanted to take care of it ourselves... So it started from there. You could hardly see a piece of money.'26

Early to Mid-January 1936 – Government Reaction

As Protector J.D. McLean toured the islands to recruit men for Company Boats between 7-23 January, he met uniform resistance. On every island, when he entered the school to assign crews, men leapt out the windows—a defiant act that became a hallmark of the strike.

J.D. McLean reported that the Torres Strait Islanders said: ‘We do not agree to work on boats’ and then walked out.27

Nau Mabaig explains the dynamics of the action on Badu / Mulgrave:

‘Mr McLean asked: ‘Why do you refuse to go on boats?’ I’m only about 16 years of age and I told all the public: ‘Come on, all of us jump through the windows.’ And all of us jump through the windows… We all rush to the village, calling out: ‘We will never sign back.'28

After witnessing similar incidents across multiple islands, JD McLean began traveling with police escorts. Deputy Chief Protector, C O’Leary was ordered to leave Palm Island and proceed to the Torres Strait Islands to prepare a report on the situation.

Responding to the strike, E.M. Hanlon—Minister for Health and Home Affairs—acknowledged the Torres Strait Islanders’ right to ‘spend their money as they earned it,’ as reported in the Brisbane Telegraph on 14 January 1936.29

Strikers were arrested, including three on Naygay / Saibai Island on 18 January 1936 for confronting the Government teacher Mr Bryant and challenging him over signing the men to Company Boats. The Naygay / Saibai Islanders had tried to have Mr Bryant dismissed in 1935, an action that led to two Councillors being dismissed.30

February - March 1936 – Escalation

In late February, the Government offered pay increases, but the offer couldn’t end the strike. Clearly the strike was not just about money, Torres Strait Islanders demanded respect and self-determination.

As the strike continued, Badu / Mulgrave Island had been visited three times by the Protector alongside the police. Thirty men were gaoled on Badu / Mulgrave Island for refusing to go back to work on the Company Boats, as reported in the Telegraph of 26 February 1936.

On the same day, Deputy Chief Protector, O’Leary reported that ‘Returned from Badu, Tuesday leaving for Murray Islands today Strike at Badu off four boats manned’. The strike was over on Badu32.

Meanwhile on Malu Kiwai / Boigu, Naygay / Saibai Island and Iama / Yam Island, despite enticements of increased wages, the lugger crews stood firm. The Malu Kiwai / Boigu and Naygay / Saibai men ‘stated they will await change of Government’. O’Leary interpreted this as Islanders hoping that control would shift from the state to the Commonwealth.33

On Mabuiag / Jervis Island the men refused to sign on to the Company Boats but were willing to work on the Master Boats.34

By 2 March 1936, O’Leary was reporting to his superiors that the strike was finished on the Eastern Islands, except for Mer / Murray Island. On Ugar / Stephen Island, the men had signed on to the Master Boats.

April - June 1936 – Pressure Mounts

On 6 April 1936, following a Queensland Cabinet decision, Townsville Police Magistrate and former Protector, G.A. Cameron, was sent to join Deputy Chief Protector O’Leary and police, to report on the administration of the Protector of Aboriginals on Thursday Island, the AIB, and its branch store35. Among his recommendations, Cameron included the following:

- Liquidation of boat debts;

- Reform of the system for appointing and dismissing local councillors;

- Separation of the roles of Police Magistrate and Protector of Aboriginals;

- Transfer of certain officials.

By 11 May 1936, Deputy Chief Protector O’Leary’s Report on the Origin and Cause of Discontent amongst Torres Strait Islanders squarely blamed Protector of Islanders J.D. McLean for excessive control, disrespect toward Torres Strait Islanders, and their complete dislike of him. Further, O’Leary pointed to poor pay, lack of accountability, heavy-handed rules, and JD McLean replacing elected councillors (particularly on Naygay / Saibai and Mer / Murray Island) with hand-picked loyalists as further causes for the strike. He also blamed the Anglican Church and storekeepers of Waibene / Thursday Island for their criticism of the protection and control regime over Torres Strait Islanders.36 Chief Protector O’Leary left the island and would not return until September.

Workers on Naygay / Saibai, Malu Kiwai / Boigu and Mer / Murray Island continued the strike.

July 1936 – Commission of Inquiry

In July 1936, the Government of William Forgan Smith convened a Commission of Enquiry in direct response to the Torres Strait Islanders’ strike. The inquiry examined:

- Grievances raised by Torres Strait Islanders; and

- Administration by the Protector of Torres Strait Islanders.

The Key Outcomes were:

- Commitments to abolish oppressive controls, including curfews and credit-only pay;

- Introduction of cash wages and improved labour conditions;

- Greater local autonomy in managing boats and community affairs.

These assurances led most strikers to return to work by late July, marking a turning point in Torres Strait governance and labour rights.37

September 1936 - Major Concessions

In September 1936 Protector McLean was removed from the Torres Strait, which was celebrated by Torres Strait Islanders.

Protector O’Leary took up duties on Waibene / Thursday Island and immediately:

- Removed the ‘Bu’ whistle, which had been used to enforce curfews on the islands,

- Provided copies of boat returns to each Company Boat captain and crews,

- Held meetings to ascertain the views of Torres Strait Islanders on ‘transfer of the powers of Government teachers to the Councils’.38

- Abolished the requirement for Protector approval for interisland travel, and

- Enabled elected Councillors, not the Protectors, to recruit the crews of the Company Boats.

By October 1936, the strike was over.

Demands of Strikers

When considering the demands of Torres Strait Islanders, it is evident the strike wasn’t just about wages—it was a fight for self-determination and the freedom to live life on their own terms. In summary, those demands were:

- ‘Abolition of the ‘Boo/Bu’ or time whistle on all Islands;

- Greater facilities for inter-Island visits without the necessity for Permits from the Government Teacher;

- The appointment of police on Islands on which Torres Strait Islanders reside,

- Conference of all Councillors to be held at the earliest opportunity;

- The Councillors shall receive a monthly report showing receipts and expenditure of their particular Island Fund;

- The institution of amended Boat Returns regarding ‘Company Boat’ transactions and the provisions that the captain of a boat shall receive one (1) such return which is the property of the Captain and Crew.’39

The Role of Allies

Torres Strait Islanders were not without allies in their struggle for rights.

Between 1933 and 1935, Anglican Bishop of Carpentaria Rev. Stephen Davies grew increasingly critical of Queensland’s ‘dictatorial methods’ toward Torres Strait Islanders. At the 1935 synod, he attacked the Protection Act 1934, calling it ‘an infringement of the rights of citizenship possessed by some of the coloured people of Queensland,’ 40 and moved a motion urging the Commonwealth to assume control of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

During the strike of 1936, Rev Davies wrote to the Governor of Queensland asserting that the system of payment, was among the major causes of the strike.41

South Sea Islander descendants and Torres Strait Islanders formed the Thursday Island Coloured Peoples Workers Association, which hired a solicitor to challenge the constitutional validity of the Protection Act 1934 amendments and engaged in wider debates on labour activism and racial politics in the Torres Strait during the 1930s.42

Shopkeepers on Waibene / Thursday Island backed the strikers, as restrictive controls on Torres Strait Islanders’ wages meant workers couldn’t freely spend their money—hurting local businesses.43

Impact

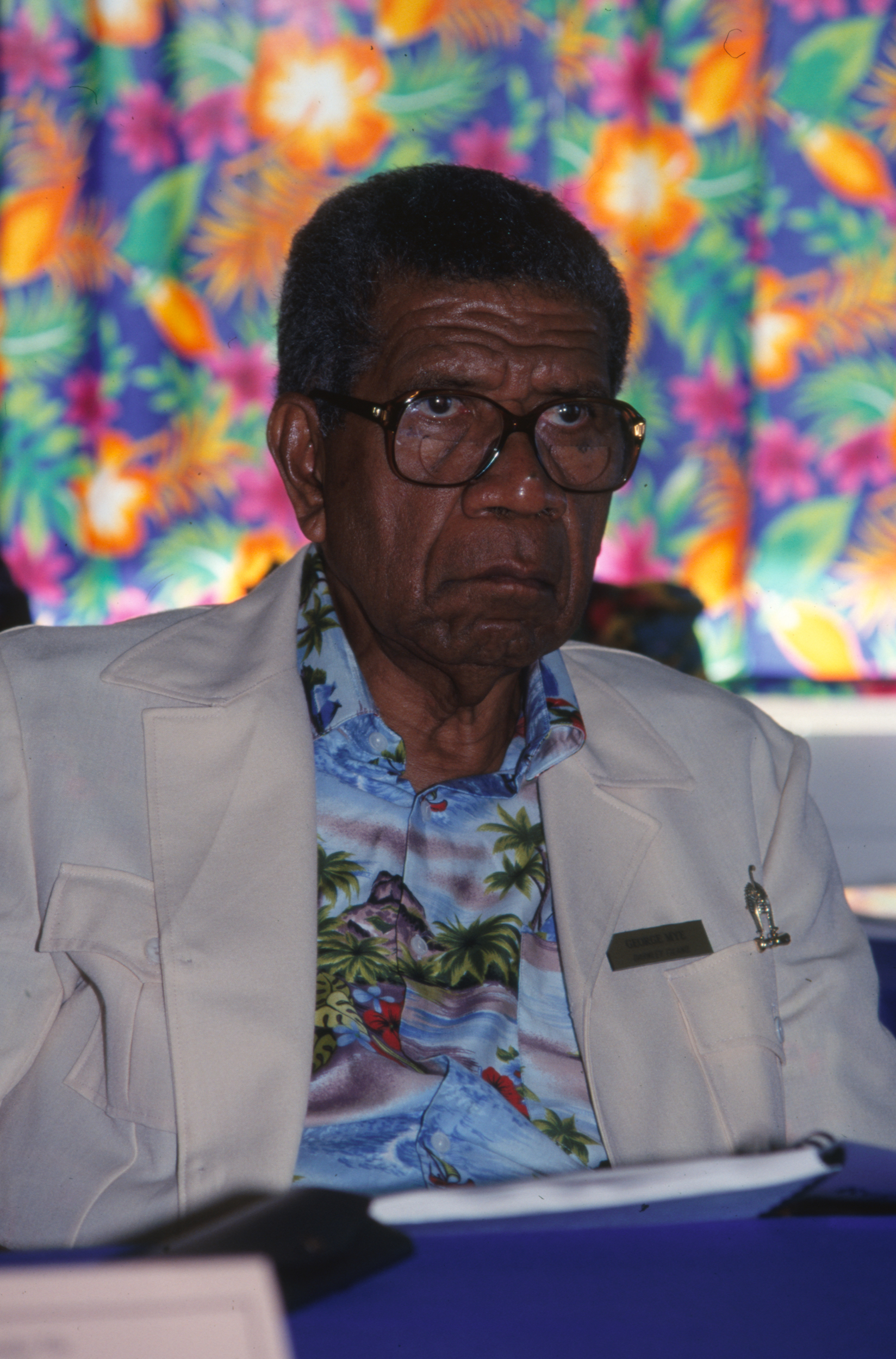

George Mye, an Erub / Darnley Island man who would later become a prominent leader in Torres Strait politics and native title, was only 10 years old during the 1936 strike. In an interview recorded by anthropologist Jeremy Beckett, Mye recalls that the Erub Le (people of Erub) “did not want to be dictated to.” He reflects on the hardships faced by mothers and children during the strike and the confiscation of the island’s boat Erub, being a reason for joining the strike. He describes how the 1937 Conference resulting as a strike demand addressed some of the concerns raised by Torres Strait Islanders.

‘I was very conscious of that push by our people now towards getting the rights of being able to run their own island themselves and well, others were saying as soon as we can get our people educated enough, we can run the thing ourselves. We don’t need white teachers to come and tell us, you know…’ George Mye.

Listen to George Mye’s story:

Attribution sound file: [BECKETT-MYE_01_Tape 7A, Beckett, J and Mye, G, Autobiography of George Mye describing his life in Zenadth Kes / Torres Strait Islands, 1988, AIATSIS Collection]

ATSIC.067.CS-A00002436, Councillor George Mye at the Launch of the new Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA), ATSIC, Waibene / Thursday Island, 1 July 1994, AIATSIS Collection.

ATSIC.067.CS-A00002436, Councillor George Mye at the Launch of the new Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA), ATSIC, Waibene / Thursday Island, 1 July 1994, AIATSIS Collection.

The 1936 strike sparked sweeping changes and set in train bold new directions for Torres Strait Islander rights that continue to this day. Unpopular local Protector J.D. McLean was ousted; new Protector Cornelius O’Leary introduced a set of amended rules or ‘New Law’ including regular consultations with elected Islander councils - giving communities a real voice. For the first time, these councils gained control over many of the powers of the teachers, the AIB, local policing and courts, marking a bold shift toward autonomy.

Beyond wages, the strike signalled a fight for autonomy and the right to self-determination.

1937 Islanders Conference Masig / Yorke Island

On 23 August 1937, O’Leary convened the First Inter Islander Councillors’ Conference at Masig / Yorke Island. Representatives from 14 Torres Strait communities attended the conference. Many of the strike leaders, strikers and lugger owners represented their islands, including:

- Tanu Nona, Fred Bowie, Jacob Bara (Badu / Mulgrave Island),

- Jacob Matthew, Gibuma ( Malu Kiwai / Boigu)

- Abiu Fauid, Saurio Bob (Poruma / Coconut Island)

- Kailu George, Tat Thaiday (Erub / Darnley Island)

- Manesa Bani, Ephraim Bani (Mabuiag / Jervis Island)

- Mau, Anau (Dauan / Mount Cornwallis Island)

- Wees Nawia, Sailor (Poid / Kubin Village)

- James William, Ned Salee, Joseph Gokisa (Mer / Murray Island)

- Lui Mills (Naghir / Mount Ernest Island)

- Mareko, Soki, Enosa (Naygay / Saibai Island)

- Ned Wakando (Ugar / Stephen Island)

- Elap Price, Mekairi George, Simeon Price (Iama / Yam Island)

- Barney Mosby, Dan Mosby and William Jack (Masig / Yorke Island)

After lengthy discussions at the Conference, unpopular bylaws, including the evening curfews, were cancelled and a new code of local representation was agreed upon.

1939 - End of the 1897 Act for Torres Strait Islanders

Changes made to the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 ceased to apply to Torres Strait Islanders. Instead, two new laws were introduced:

- The Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act 193944 – applied mainly to Aboriginal people, and

- The Torres Strait Islanders Act 1939 (TSI Act) – created a separate legal regime for Islanders.

The TSI Act incorporated the changes agreed at the 1937 Conference, including constituting Island Councils under an Act of Parliament for the first time45, with local government provisions enacted in the following terms:

‘The Island Council shall have delegated to it the functions of the local government of the reserve, and shall be charged with the good rule and government of the reserve in accordance with island customs and practices, …’46

For Torres Strait Islanders, progress was limited. Authority remained with the Director of Native Affairs and the Protector of Islanders until the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Act 1965, which replaced the Director of Native Affairs with the Director of Aboriginal and Island Affairs and ended the Director’s role as legal guardian of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.47 Repeal of classifying certain Torres Strait Islanders as ‘assisted Islanders’ did not occur until the introduction of the Torres Strait Islander Act 1971.

The uprising of 1936 was more than a strike—it was a spark that ignited a legacy of resistance and pride. From those bold voices in the Torres Strait rose a culture of defiance against injustice, a determination to claim dignity and rights. That spirit:

- surged again in the 1940s when Torres Strait Islanders fought for equal pay in the military;

- roared through the ‘Border Not Change’ campaign of 1976;

- powered the cessation movement of the 1980s; and

- reached its historic crescendo in the Mabo Native Title claim and in the 2022 ruling of the UN Human Rights Committee that Australia violated their rights to culture, family, and home due to climate change impacts, establishing an international precedent on climate justice.

Each stand was a testament to courage - a relentless tide against oppression that still shapes the Torres Straits today.

References

- 1936 'ON STRIKE AG’NST GOVERNMENT', The Workers' Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1923 - 1939), 17 January, p. 3., viewed 28 Nov 2025.

- 1936 'TORRES STRAITS STRIKE', The Workers' Weekly (Sydney, NSW: 1923 - 1939), 21 January, p. 3., viewed 28 Nov 2025.

- McNiven, I year, Torres Strait Islanders: The 9000-Year History of a Maritime People, viewed 27 November 2025.

- Bipotaim – the long period of time before Christianity was introduced to the Torres Strait in 1871.

- Queensland became a colony of Britain in 1859. Prior to this it had been a colony of the British administered Colony of New South Wales, see https://www.qld.gov.au/about/about-queensland/history/creation-of-state.

- bêche-de-mer are also known as sea cucumber or trepang

- Museum of Australian Democracy, Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879, viewed 28 November 2025.

- Queensland Government, 2018, Erub (Darnley Island), viewed 30 November 2025.

- Hodes, J 2017, John Douglas and the Asian Presence on Thursday Island, p. 203 in Navigating Boundaries: The Asian diaspora in Torres Strait, edited by Anna Shnukal, Guy Ramsay and Yuriko Nagata, published by ANU eView, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, viewed 30 November 2025.

- Island head man.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 131, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia. See also, The Conversation 2024, A Brief Political History of Torres Strait Islander peoples, viewed 30 November 2025.

- Beckett, J 1989, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism, p. 45, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

- Torres Strait Islanders were not officially counted as part of the population.

- The Conversation 2024, A Brief Political History of Torres Strait Islander peoples, viewed 30 November 2025.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 140, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Mullins, S 2001, Mullins on Social Control in the Torres Straits, viewed 30 November 2025.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 161, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Ibid, p. 161-164.

- Curfews meant that single men and children had to be inside homes by 6pm. The curfews were controlled by the ‘bu’ whistle.

- Queensland Government, 2020, Report from the Treaty Working Group on Queensland’s Path to Treaty, viewed 5 December 2025.

- AIATSIS, To Remove and Protect, Qld, Protection of Aboriginals and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Amendment Act 1934, viewed 5 December 2025.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 198, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- 1935 'UNRULY NATIVES.', The Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909 - 1965), 20 December, p. 9, viewed 10 Dec 2025,

- Beckett, J 1989, Torres Strait Islanders: Custom and Colonialism, p. 53-54, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 188, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 188, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Ibid, p. 191.

- Ibid, p. 189.

- Ibid, p. 182.

- Ibid, p. 192 and 198.

- 1936 'TORRES STRAITS STRIKE', The Workers' Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1923 - 1939), 21 February, p. 3, viewed 03 Sept 2025.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 199, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Ibid, p. 199.

- Ibid, p. 199.

- Ibid, p. 200.

- Ibid, p. 196.

- Wetherell, D 2004, The Bishop of Carpentaria and the Torres Strait Pearlers’ Strike of 1936, The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 39, no. 2, 2004, pp. 185–202, viewed 11 December 2025.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 200, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Sharp, N 1982, Culture Clash in the Torres Strait Islands: The Maritime Strike of 1936, viewed 28 November 2025.

- Wetherell, D, 1993, From Samuel Mcfarlane to Stephen Davies: Continuity and Change in the Torres Strait Islands Churches, 1871-1949, Pacific Studies, Vol 16, no. 1, March 1993, p. 19, viewed 28 November 2025.

- Ibid, p. 20.

- Sharp, N 1993, Stars of Tagai: The Torres Strait Islanders, p. 185, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, Australia.

- Ibid, p. 185-186.

- AIATSIS, To Remove and Protect, viewed 5 December 2025.

- S. 3, Torres Strait Islanders Act 1939 (Qld), viewed 12 December 2025.

- S. 18, Torres Strait Islanders Act 1939 (Qld), viewed 12 December 2025.

- AIATSIS, To Remove and Protect (Qld), viewed 12 December 2025.