The following content may include offensive and/or hurtful language. It reflects the language of the time and is not condoned by AIATSIS.

The items in this story are of a historical nature and do not reflect current electoral procedures. For current and up to date election information, please visit the Australian Electoral Commission website.

We owe it to the world […] to grant the Aborigines their right, as citizens, to vote or take an active part in the development of their country.

George Abdullah, Noongar activist and community leader, 1961

The history

The history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voting rights is a long and complex one. Contrary to popular misconceptions, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people did not gain the vote in the 1967 Referendum. In fact, before Federation on 1 January 1901, some Aboriginal people had been entitled to vote in a number of Australian colonies. Each colony could determine who and who was not allowed to vote. This situation led to some curious differences in voting rights. For example, Aboriginal women in South Australia were able to the vote in 1896, before non-Indigenous women did in either Sydney or Melbourne. Queensland and Western Australia enacted legislation under which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were barred from voting in elections from the end of the 19th century until the 1960s. However, despite the legal exclusions, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults were able to vote.

After Federation, there was heated debate over who should be eligible to vote in the elections for the newly-established Australian government. There was very strong opposition by a significant number of politicians who campaigned against giving all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults the vote. Senator Alexander Matheson expressed the view that such a step would be “repugnant and atrocious”. Senator Richard O’Connor, on the other hand, made a passionate plea for equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It would be a monstrous thing, an unheard of piece of savagery on our part, to treat Aborigines, whose land we were occupying, to deprive them of any right to vote in their own country simply on the grounds of their colour.

Richard O'Connor, politician and judge, 1902

Despite O’Connor’s insightful words, the Commonwealth Franchise Act of 1902 further restricted Aboriginal voting rights. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were barred from participating in Commonwealth elections, unless they were already eligible to vote in state elections.

Under the Constitution, individual states had the right to legislate the definitions of who was considered to be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander. These definitions could be used to determine who was and who was not eligible to vote. Over the first half of the twentieth century, changes to the definitions often lead to further restrictions on voting rights. Because of these policies, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were excluded from participating in the political process.

Voting rights for all

I ask for franchise for all people of Aboriginal blood

Sir Douglas Nicholls, footballer, pastor and activist, 1961

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, a growing number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander campaigners sought to gain rights for and improve the living conditions of their people. Over time, their efforts led to changes in legislation.

In 1949, the Electoral Act was amended to extend the Federal vote to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who had served in the armed forces, and to continue to enfranchise those who had the right to vote in their own state.

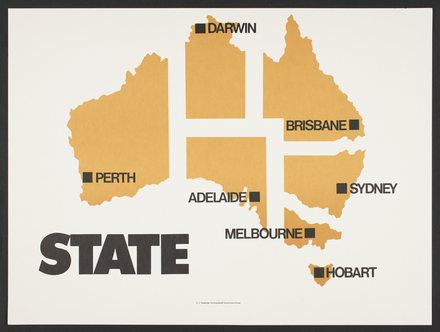

In 1961, following sustained campaigning by activist groups such as the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, the Federal Government convened a Select Committee on Voting Rights of Aborigines. The Committee’s Report estimated that approximately 30,000 people living in the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia were excluded from the vote. As a result of the Committee’s findings, the Commonwealth Electoral Act was amended in 1962 to give all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults the right to vote in federal elections, although enrolling was not made compulsory.

Legislators were concerned that some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people might choose not to exercise their right to vote and might be penalised for not voting. For this reason, the Act stressed that enrolment was optional. The new Act also made encouraging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to enrol an offence. This anomalous situation remained in effect until 1983, when voting was made compulsory for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, in line with the rest of the nation.

With the expansion of voting rights, a wide range of material was produced to inform diverse groups of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of their rights and obligations in regards to the vote. This exhibition highlights some of the fascinating items to be found in the world’s largest collection dedicated to Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and histories.

First forays into electoral education

In 1962, a major concern was whether newly-enfranchised (given the right to vote) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would have sufficient understanding of the Australian parliamentary system and voting procedures to exercise their new rights. As activist and poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal had noted to the Select Committee hearings, no such concern over comprehension and literacy was expressed regarding non-Indigenous voters.

Writing in The Melbourne Herald about the situation of Northern Territory Aboriginal people, Noel Hawken put the issue bluntly:

How do you explain voting rights, preferential voting and the secret ballot to aboriginals [sic] whose social role is so limited that they are not even allowed to own property, go into a bar, or marry outside their own color without permission?

In September 1962, Charles “Jack” White, a senior official with the Commonwealth Electoral Office (the forerunner to the Australian Electoral Commission), initiated an educational program to provide information to Aboriginal voters. The program was designed specifically for use in the Northern Territory, which was where the first election following the 1962 Act was held. It sought to instruct adults who had just gained the right to vote, and to educate future generations of voters.

Franchise for Aborigines

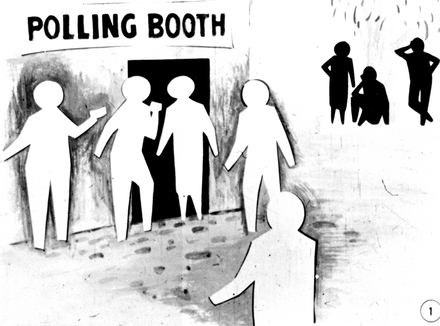

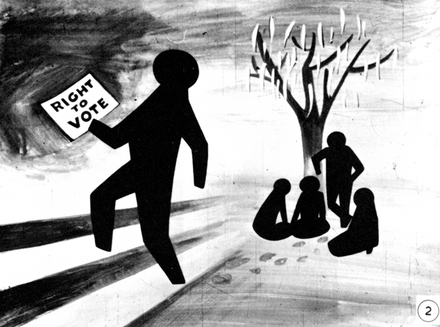

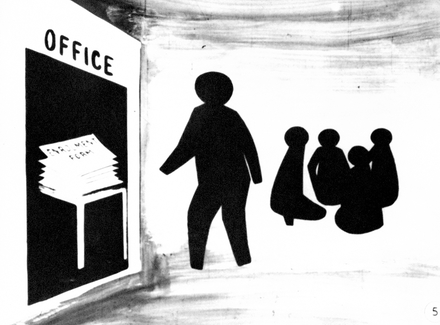

At the time, election education materials consisted of English-language pamphlets with no illustrations. White commissioned the production of more versatile visual aids—a filmstrip and picture cards—that could be used to deliver instruction in Aboriginal languages as well as English.

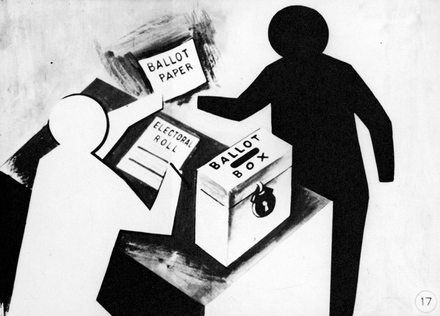

The filmstrip Franchise for Aborigines was a series of images that could be projected onto a screen or wall. It was the first effort to illustrate the Australian parliamentary system and voting procedures for an audience presumed to have little knowledge of either. The filmstrip focused on the mechanics of the voting process with little discussion of the functions of government and how voting might impact on peoples’ lives.

These early educational materials established a set of images that visualised the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian democratic system. These images reoccur in many of the later materials in this exhibition, with subtle differences reflecting changing government policies and the growing recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as active participants in the political process.

Franchise for Aborigines (1962), Art Direction by Newman Rosenthal, Artwork by Eric Thake. Produced by the Department of Audio-Visual Aids, The University of Melbourne for Commonwealth Electoral Office.

Franchise for Aborigines (1962), Art Direction by Newman Rosenthal, Artwork by Eric Thake. Produced by the Department of Audio-Visual Aids, The University of Melbourne for Commonwealth Electoral Office.

Franchise for Aborigines (1962), Art Direction by Newman Rosenthal, Artwork by Eric Thake. Produced by the Department of Audio-Visual Aids, The University of Melbourne for Commonwealth Electoral Office.

Franchise for Aborigines (1962), Art Direction by Newman Rosenthal, Artwork by Eric Thake. Produced by the Department of Audio-Visual Aids, The University of Melbourne for Commonwealth Electoral Office.

A growing demographic

The extension of federal voting rights to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, together with the continuing efforts of Aboriginal campaigners and their supporters, contributed to the expansion of voting rights to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in state elections.

Voting rights for Aboriginal people in Western Australia were extended in 1962; the Native Welfare Act, passed in 1963, repealed earlier acts which had restricted the civil liberties of Aboriginal people in Western Australia.

In 1964, the Western Australian Department of Native Welfare produced the pamphlet Citizens to explain these legislative changes to Aboriginal people affected by them. It is the earliest item in this exhibition that explicitly communicates with an urban Aboriginal audience.

In 1965, the Commonwealth Electoral Office updated the visual aids, using similar layouts to the 1962 filmstrip but with naturalistic drawings replacing the abstract silhouettes. Like the 1962 materials, the images on these cards are designed for Aboriginal audiences in rural and remote communities, predominantly in Western Australia where Jack White had taken the role of Chief Commonwealth Electoral Officer for that state.

In 1965, Queensland was the last state to fall in line and pass legislation enabling all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to vote in state elections.

The increasing public awareness of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander electors over the 1960s is demonstrated by a Weet-Bix card produced in 1969. The card was one of a collectable series of cards distributed in Weet-Bix cereal boxes, depicting various aspects of Aboriginal lives and cultures. It features an image of Aboriginal people exercising their right to vote. The accompanying text was emphatically positive about the impact of extended voting rights:

“[…] increasing numbers of Aborigines are voting at each election. The day may not be far away when an Aborigine will be elected to Parliament”.

Indeed, the day was not far off: in 1971, Neville Bonner was appointed by the Queensland Liberal Party to fill a vacancy as a senator for Queensland, becoming the first Aboriginal person to sit in the Commonwealth parliament. It was a historic appointment and he was subsequently returned to office in the 1972 election.

“First and foremost I participate […] as an Australian citizen. […] As an Australian, I am concerned for the future of my country, for the welfare of its people and for the quality of life that they enjoy.”

Neville Bonner, maiden parliamentary speech, 1971

Talking about voting

The 1970s saw the growing assertion of distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identities and cultures. This social context was reflected in electoral education materials that featured more active roles for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the electoral process, as well as the production of these materials in Aboriginal languages.

In 1977, the Australian Electoral Office (AEO), as it was then called, intensified its educational efforts. That year saw a Federal election in December, as well as a number of state elections and an election to choose candidates for the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC).

As with previous efforts, the education program primarily focused on the mechanics of voting.

Much of this material, including these booklets, was produced for voters living in remote communities in Western Australia, as well as in remote areas of the Northern Territory and South Australia.

Jimmy Little - What you should know for election day

Popular Yorta Yorta country music performer Jimmy Little appeared in an AEO instructional film called What you should know for election day. Jimmy Little provided information on a number of electoral topics, including absentee and postal voting, and performed several of his well-known songs.

Little’s popularity across Aboriginal communities made him the ideal choice for this film, the first to feature a celebrity to promote engagement with the electoral process.

Instructional posters

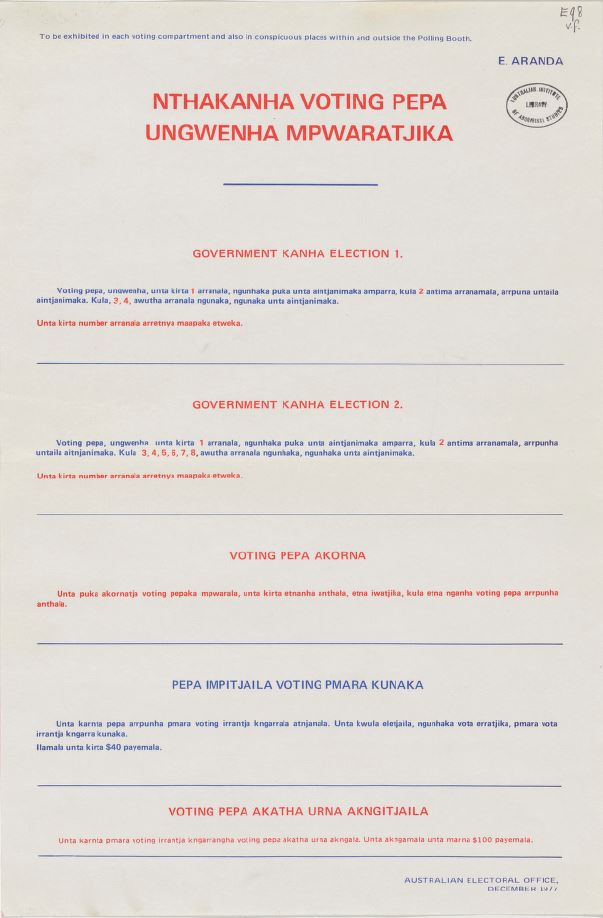

Instructional posters in a range of Aboriginal languages were produced for display at polling booths for the 1977 Federal election. The selection of languages focused on languages spoken in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia, such as Garrwa, Iwaidja, and Arrente.

The AEO also distributed cassette tapes featuring Slim Dusty, another country music singer popular among many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, to explain the NAC election process. On the reverse side of the tapes, this information was translated into each of 17 Aboriginal languages.

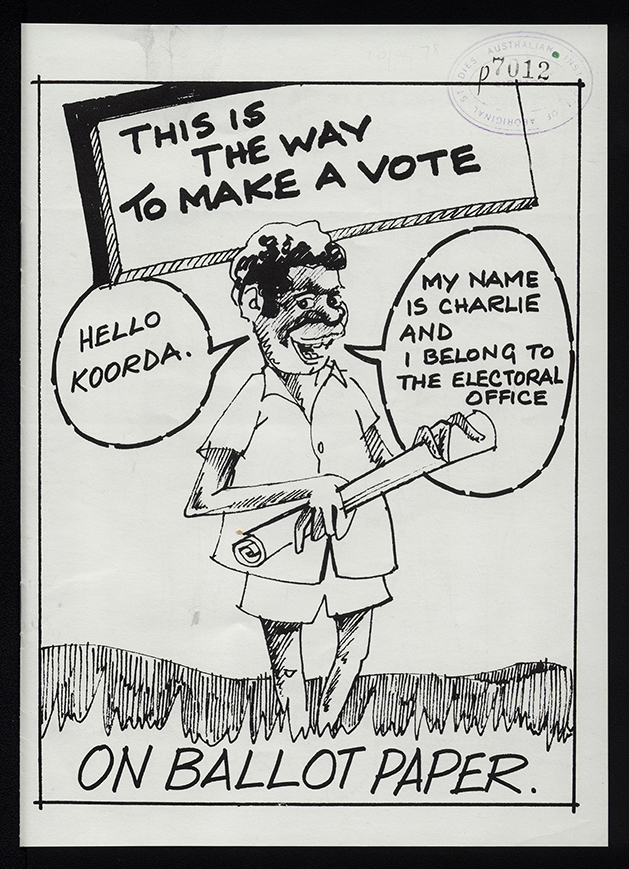

This is the way to make a vote was produced in comic book style, using the character of an Aboriginal electoral officer to explain the intricacies of preferential voting. It was produced for communities in Western Australia. The choice of an Aboriginal officer reflects the changing involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the electoral process.

The Aboriginal Electoral Education Program

Building on the intensified educational efforts begun in 1977, the Aboriginal Electoral Education Program (AEEP) was established in June 1979. The program initially was carried out in Western Australia and South Australia before being expanded to the Northern Territory.

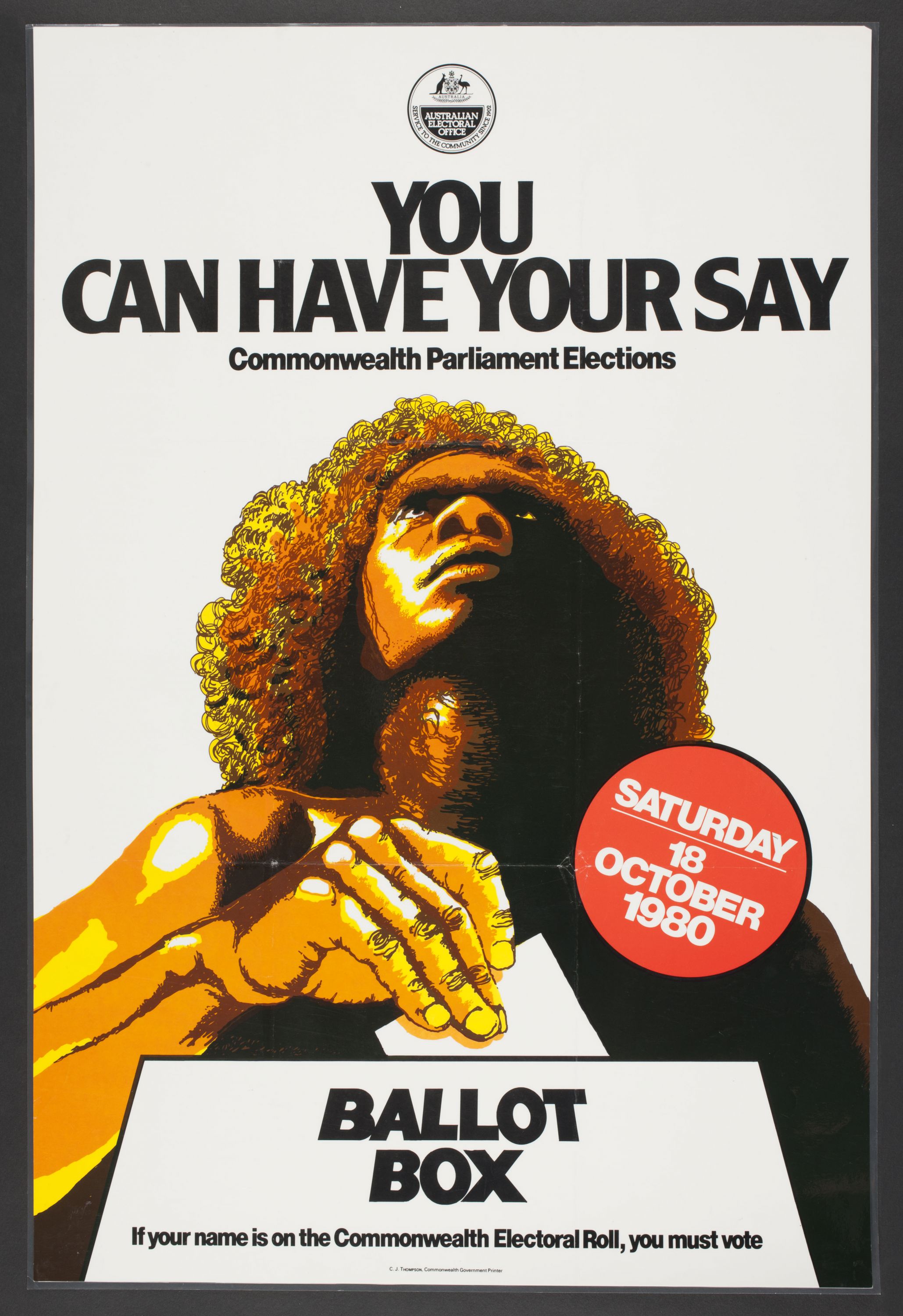

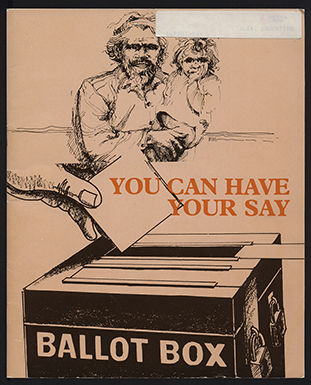

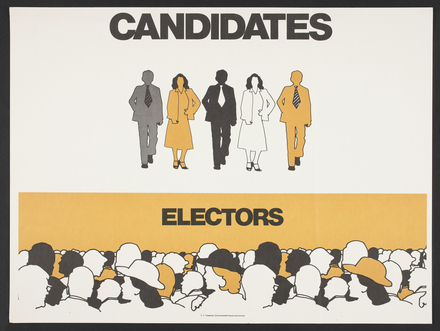

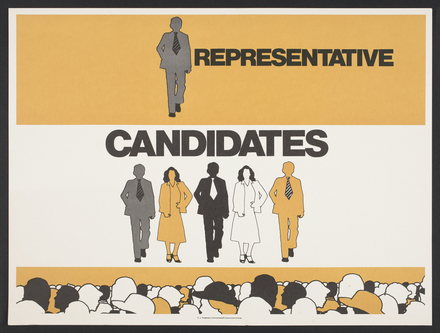

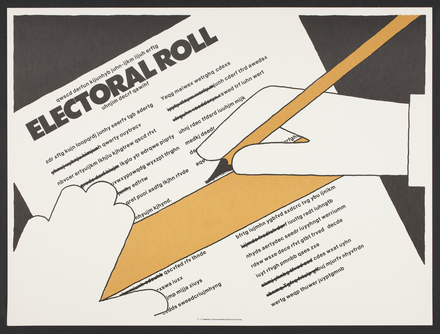

The new program was entitled You Can Have Your Say. The focus of the program shifted from earlier efforts that had only addressed the mechanics of the electoral process, with a central message emphasising active participation in the democratic process. The bold imagery reflected 1970s design as well as the iconography of the decade’s activism.

The educational package included new audio-visual material featuring Jimmy Little, the You Can Have Your Say booklet, sample ballot papers and a set of poster cards. The material for You Can Have Your Say was produced by the AEO in conjunction with the WA Department of Education’s Aboriginal Adult Education Division.

You can have your say

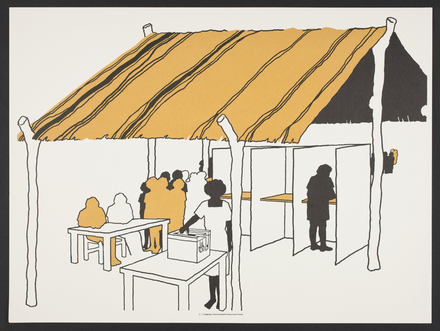

Beginning in 1979, two teams travelled with caravans to Aboriginal communities in Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. They visited communities for a period of four and five days and conducted electoral education classes in consultation with community elders and leaders. The program also distributed packages of the electoral education material for continued use in Aboriginal communities.

The purpose of the program was to teach an understanding of the parliamentary and electoral system. Legislation was still in effect that made it an offence to encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to enrol to vote. However, in addition to providing instruction on the basics of electoral procedures, the program also sought to encourage “Aboriginal people to value the rights and obligations implicit in the parliamentary system”. The program highlighted the value of participation in the electoral process. Unlike earlier educational material, it portrayed Aboriginal people as active participants in the electoral process, including images of an Aboriginal candidate.

Parliament House [sic], Darwin. You Can Have Your Say poster cards, Australian Electoral Office (1979). AIATSIS Rpf HOW.

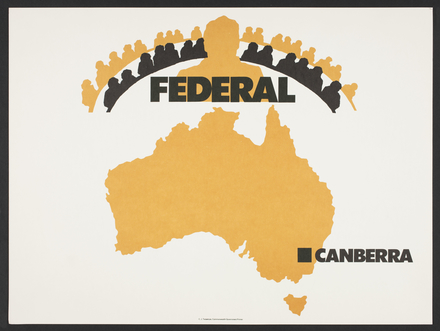

Parliament House, Canberra. You Can Have Your Say poster cards, Australian Electoral Office (1979). AAIATSIS Rpf HOW.

Candidates and electors. You Can Have Your Say poster cards, Australian Electoral Office (1979). AIATSIS Rpf HOW.

Representative and candidates. This poster was produced for the 1980 Federal Election. You Can Have Your Say poster, Australian Electoral Office (1980). AIATSIS M1063.

Electoral roll. You Can Have Your Say poster cards, Australian Electoral Office (1980). AIATSIS Rpf HOW.

Aboriginal Votes Count: The Australian Aboriginal Electoral Information Service

“More than ever, Governments are sitting up and taking notice of Aboriginal people. More than ever, the Aboriginal voice is being listened to.”

Aboriginal Votes Count pamphlet

The 1980s saw a more visible presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures in Australian public life, along with greater awareness of the struggles faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In 1983, amendments to the Electoral Act made enrolment compulsory for all Australians, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults. The earlier restriction against encouraging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to enrol was removed. This change required a concerted effort on the part of the re-named Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) to ensure the enrolment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters, who may not have previously been enrolled.

In 1985, the AEEP and replaced with the Australian Aboriginal Electoral Information Service (AEIS). The AEC’s new service was different to previous efforts in that it aimed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self-management in electoral matters. This aim was in keeping with wider policy shifts occurring across government.

The AEIS sought to work with Indigenous communities and organisations to promote the enrolment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters. The program also included the training of Aboriginal Community Electoral Assistants. The AEIS produced a wide range of educational material to promote enrolment, voting and participation in the democratic system.

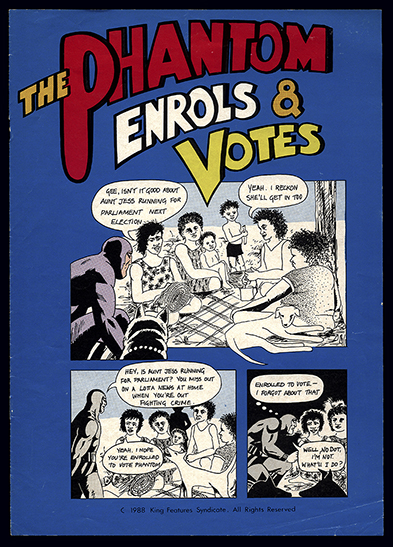

The Phantom Enrols and Votes

Towards the end of the 1980s, the AEC sought new and more engaging ways to communicate electoral information to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voters. Materials including comic books and vibrant, large format posters were produced.

The message also began to change, emphasising the responsibilities of elected representatives to address the needs and aspirations of their electorates. Individuals are encouraged to vote as a way to assert their rights as citizens, and their desires for the future for themselves and their communities.

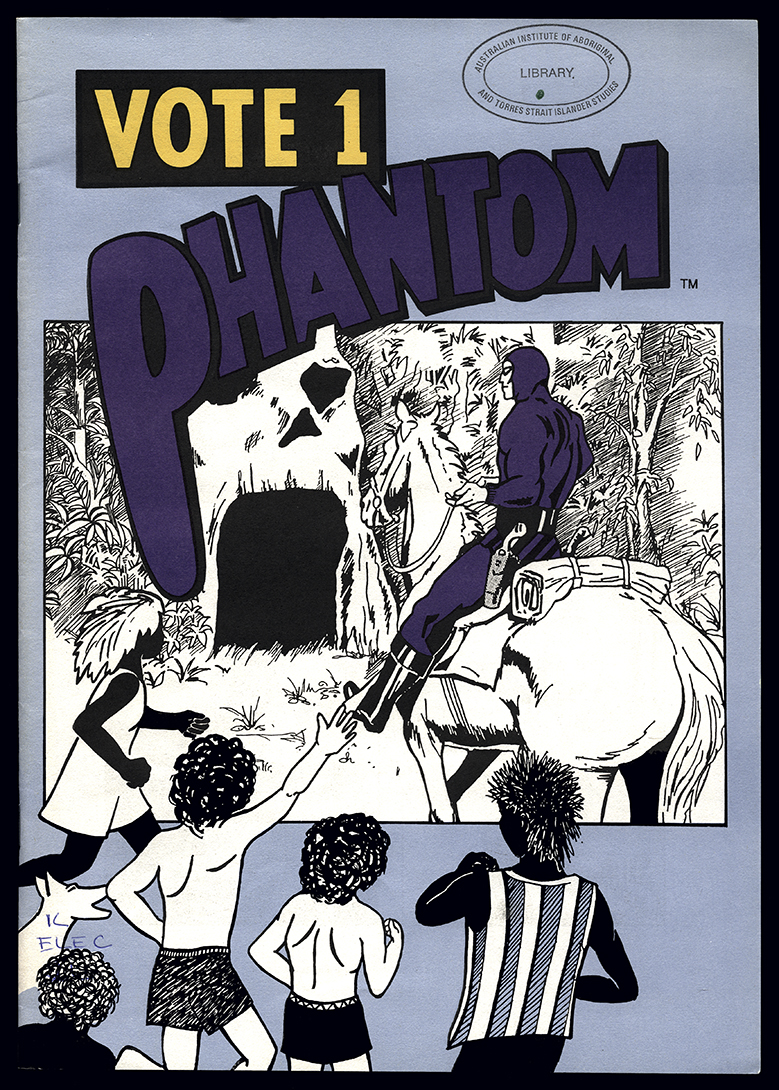

In 1988, the popular comic book figure the Phantom was recruited for use in electoral education material. The Phantom was and continues to be a favourite character in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and was considered an ideal way to engage with potential voters.

Like earlier educational materials, the comic book was a format chosen to appeal to a wide range of age groups, including children who would become future voters. Both comics were designed by Garage Graphix, a not-for-profit community art organisation comprised of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous artists and designers based in western Sydney.

- The 1988 comic book The Phantom Enrols and Votes focused on encouraging enrolment and explaining voting procedures.

- In Vote 1 Phantom, issued in 1990, the Phantom is more familiar with the electoral process and successfully runs for office in the local shire council election.

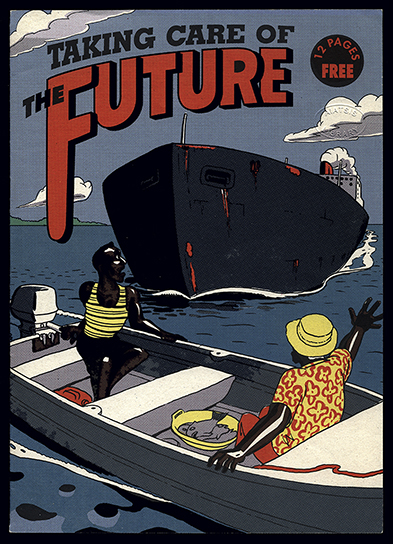

Taking Care of the Future

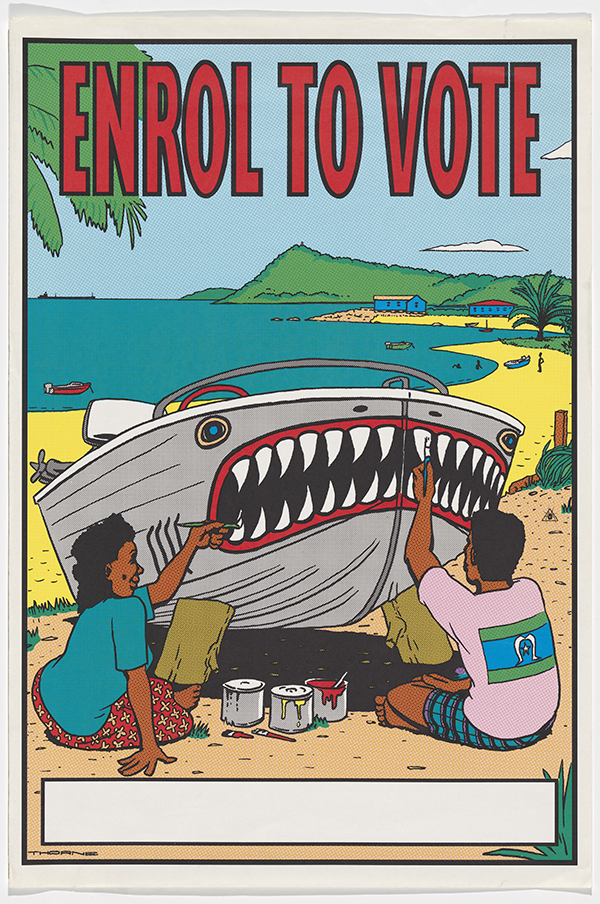

Taking Care of the Future (1993) is another comic book, focused on Torres Strait Islander issues. The artwork for this comic book was drawn by Tebrikuna artist Tony Thorne, working for Redback Graphix, who also drew the accompanying poster shown below. The central characters, Athé and Kusa, investigate how they can deal with their concerns about the impact of oil tankers passing close to their home.

The Phantom Enrols and Votes (1988), Australian Electoral Commission. Artwork by Garage Graphix. Copyright King Features Syndicate, Inc TM Hearst Holdings, Inc.

The Phantom Enrols and Votes (1988), Australian Electoral Commission. Artwork by Garage Graphix. Copyright King Features Syndicate, Inc TM Hearst Holdings, Inc.

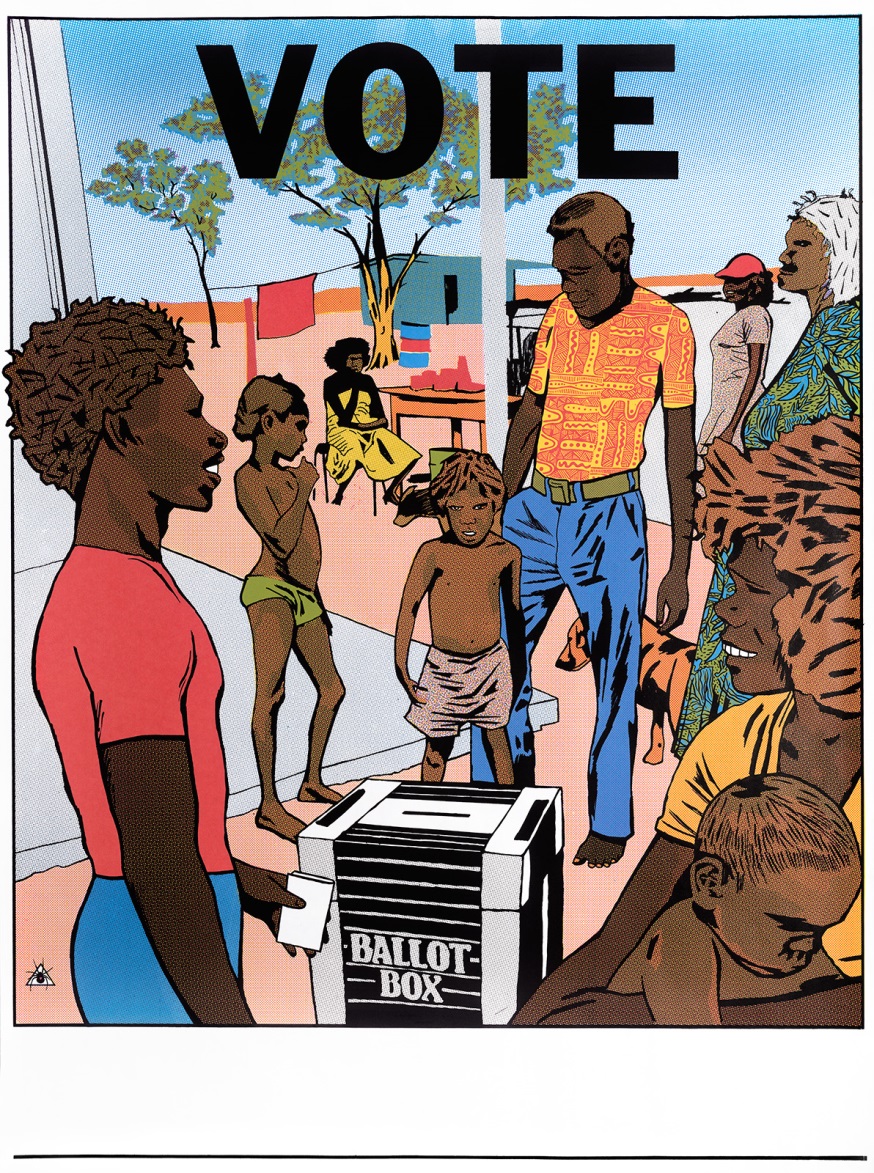

My Voice for My Country

The AEC commissioned a series of posters by Aboriginal and non-Indigenous designers from the Redback Graphix artists’ collective in Wollongong. The designers used visual imagery rather than written text to convey the messages. The posters were recognisable by their distinct and colourful style, and became renowned for their visual appeal.

Enrol to Vote (1993). Design by Tony Thorne (Tebrikuna), printing by P&R Screenprinting Pty Ltd. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1869.

Enrol to Vote (1993). Design by Tony Thorne (Tebrikuna), printing by P&R Screenprinting Pty Ltd. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1869.

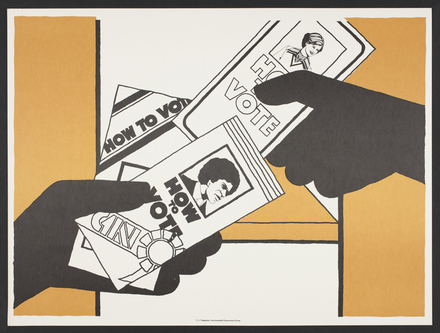

Vote (1987). Design by Marie McMahon, printing by Peter Curtis. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1237.

Vote (1987). Design by Marie McMahon, printing by Peter Curtis. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1237.

Vote: My Voice for My Country (1993). Design by Michael Callaghan, printing by P&R Screenprinting Pty Ltd. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1870.

Vote: My Voice for My Country (1993). Design by Michael Callaghan, printing by P&R Screenprinting Pty Ltd. Redback Graphix for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Electoral Information Service, Australian Electoral Commission. AIATSIS M1870.

Continuing impact

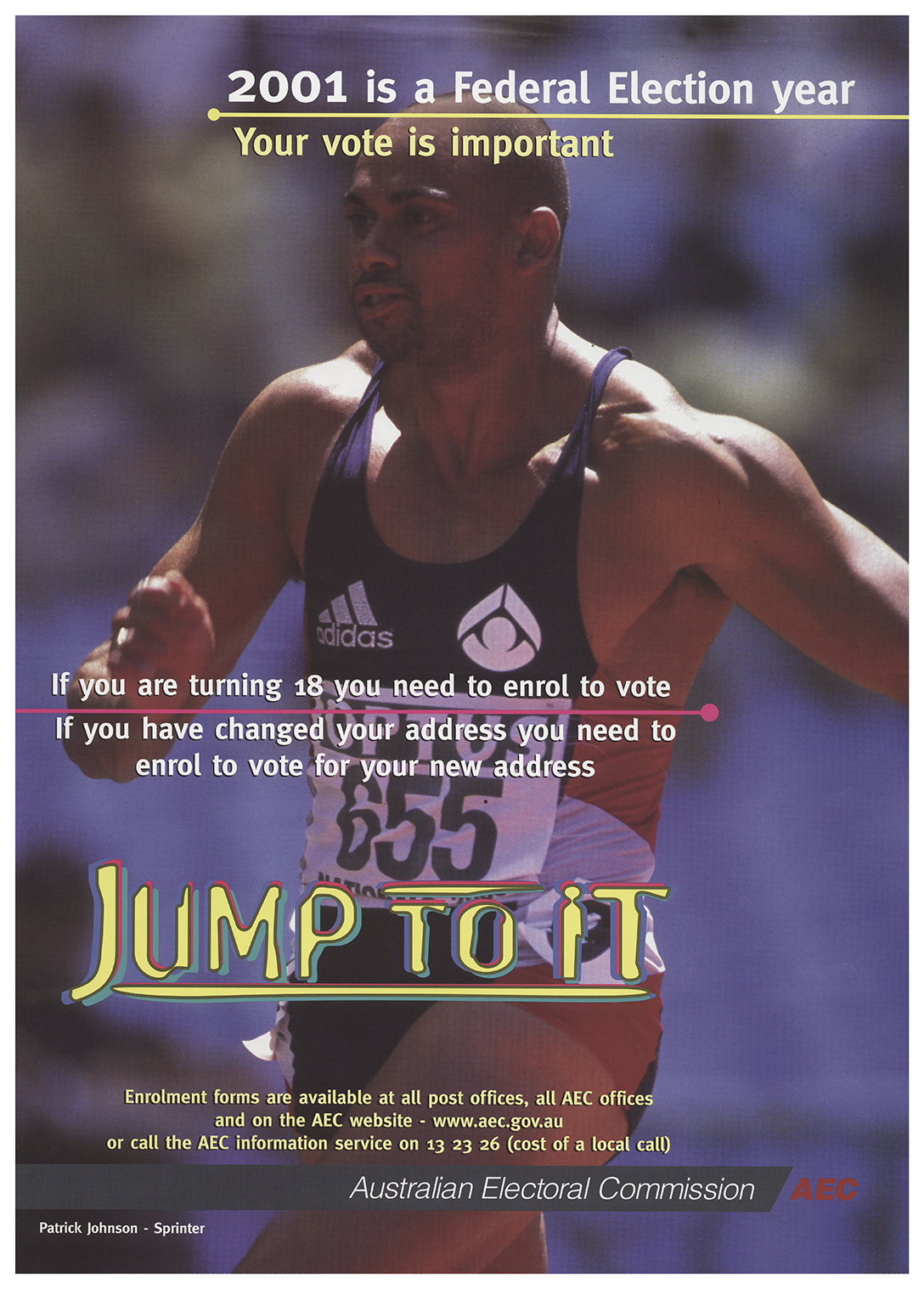

As Australia entered the 21st century, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander achievements, role models, and contributions continued to be prolific. The Australian Electoral Commission continued to make ongoing efforts to educate and empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly youth, in the electoral process.

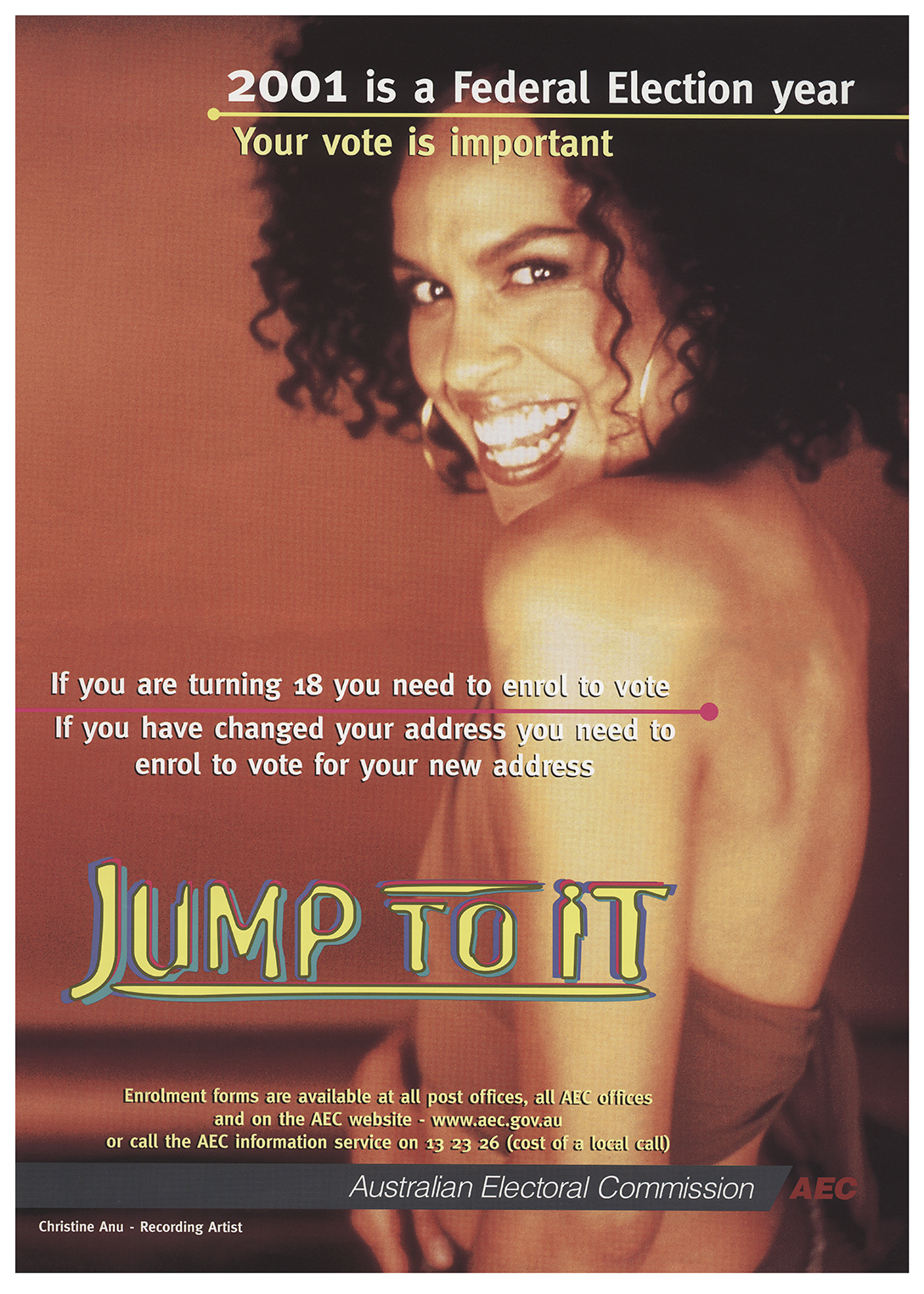

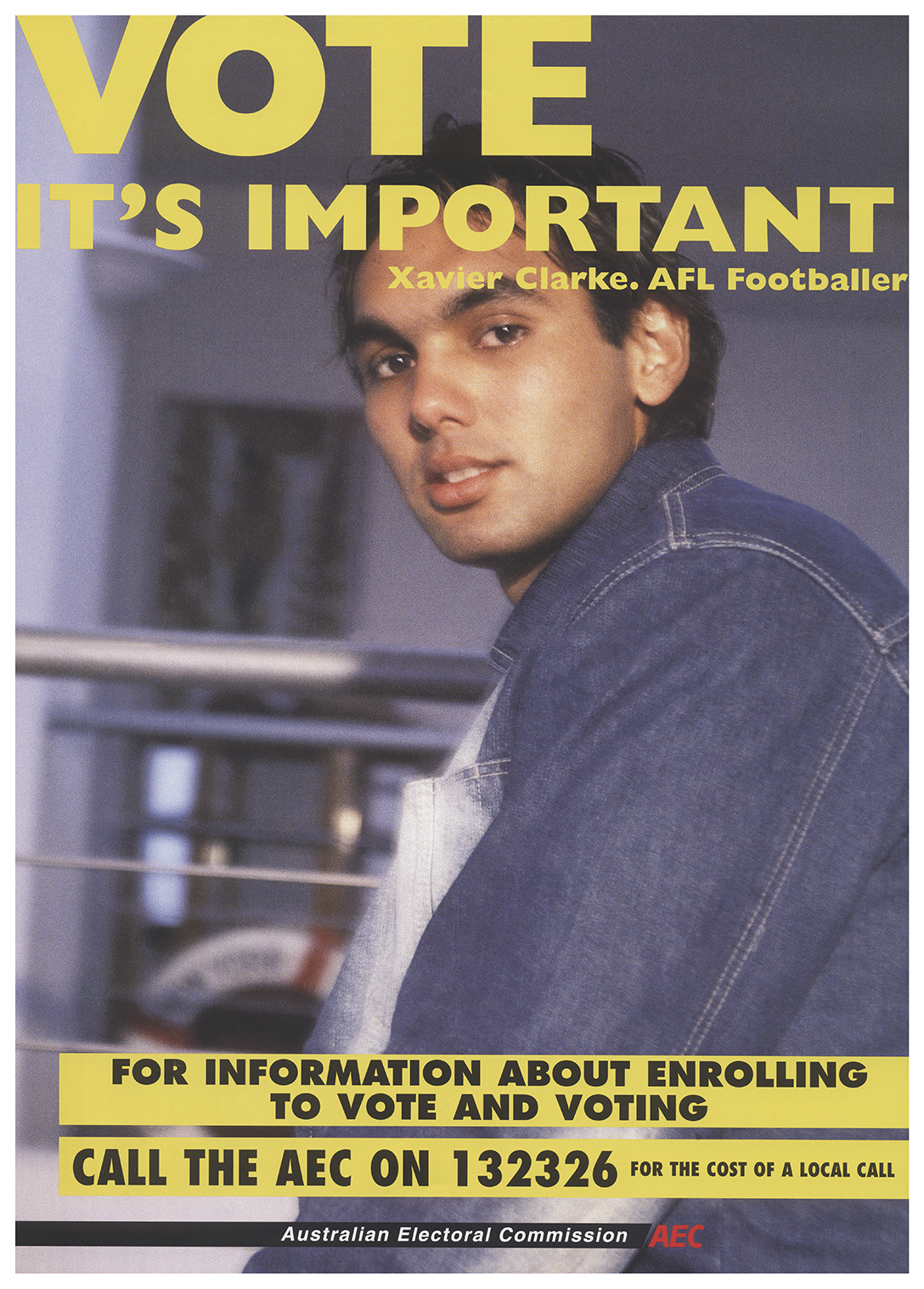

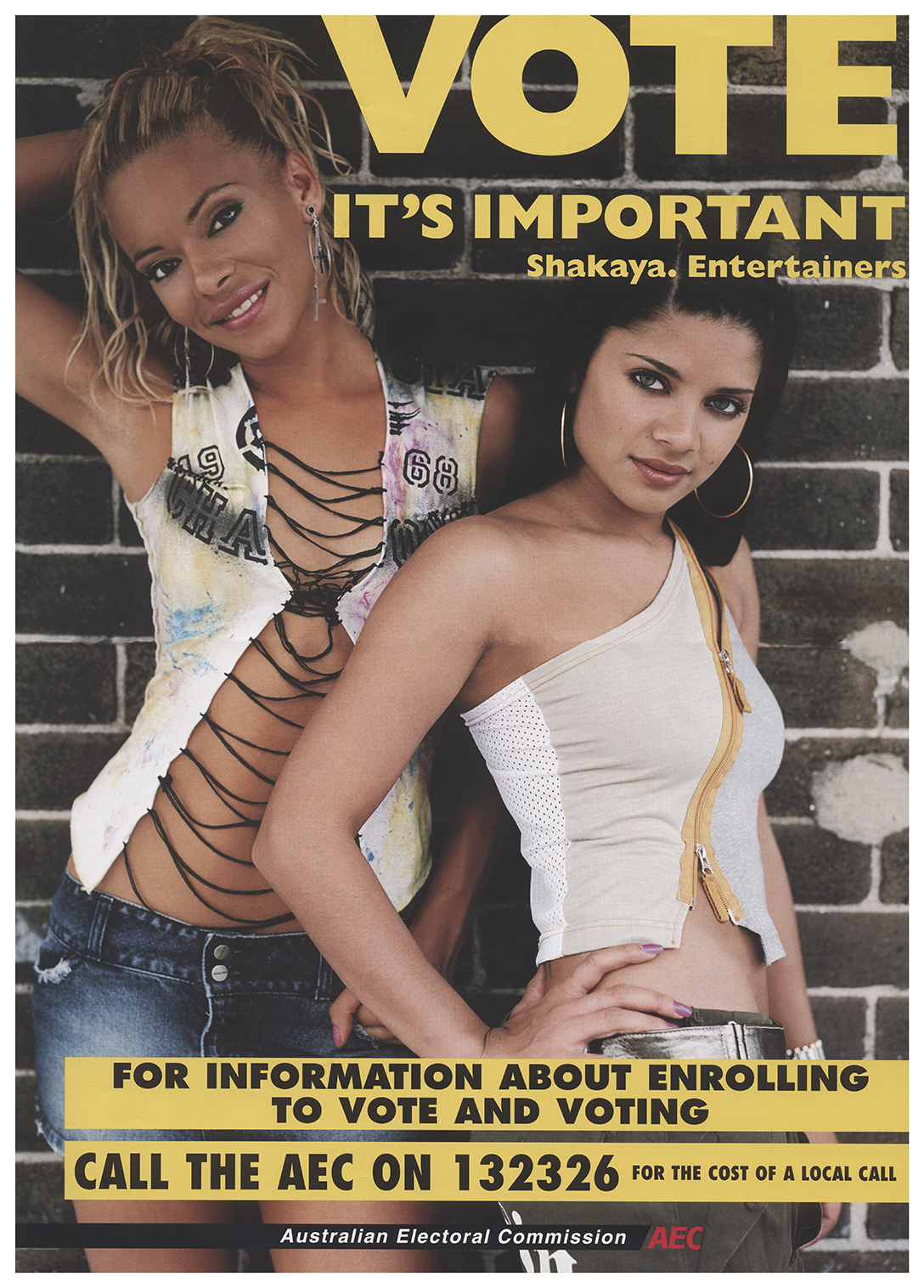

A 2001 campaign, Jump to it, featured celebrities including singer Christine Anu, AFL player Xavier Clarke and Olympic Gold medallist Cathy Freeman. The Vote, it’s important campaign was produced for the 2004 Federal election, and also included prominent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander role models such as athlete Kyle Vander Kuyp, and Simone Stacey and Naomi Wenitong, from the musical group Shakaya. Visits to communities, and the production of resources in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, continued to be an important part of the provision of information to voters.

“I vote at every election and I think it is very important that I have a say. I think it is very important that we continue to have a voice.”

Christine Anu, performer, 2012

Acknowledgements and references

-

Acknowledgements

AIATSIS would like to thank the following individuals and organisations for their assistance in the production of this story:

- Australian Electoral Commission

- Bronwyn Barwell

- Marla Guppie

- Alistair Legge

- Marie McMahon

- Lin Mountstephen

- Paula Nesci

- Frances Peters-Little

- Will Sanders

- Sanitarium Health & Wellbeing Company

- The University of Melbourne Archives

- Tony Thorne

-

References

Abdullah, Yasmin Jill. “Abdullah, George Cyril (1919–1984).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Australian Electoral Commission. “Louder than One Voice”, Calendar, 2012

Australian Electoral CommissionAustralian Electoral Office. “The Australian Electoral Office and Aboriginals.” In Service Delivery to Remote Communities, edited by P. (Peter) Loveday. Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit, 1982.

Bolger, Audrey, and Hilary Rumley. “Scandal in the Kimberleys: Voting Rights for Black Australians.” Legal Service Bulletin 3 (December 1978): 221.

“Voting Rights for Black Australians.” Legal Service Bulletin 4 (1979): 39.

Bonner, Neville Thomas (1922-1999)

Broome, Richard. “Nicholls, Sir Douglas Ralph (Doug) (1906–1988).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Chesterman, John. Civil Rights : How Indigenous Australians Won Formal Equality. University of Queensland Press, 2005.

“Defending Australia’s Reputation How Indigenous Australians Won Civil Rights Part One.” Australian Historical Studies 32, no. 116 (April 1, 2001): 20–39.Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962

Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary debates: Senate: official Hansard, 10 April 1902.

Ducker, P. A., and E. P. Milliken. “Voting Rights for Northern Territory Aborigines.” Australian Territories 3, no. 1 (1963): 34–37.

“Extension of Franchise to Aboriginal Natives of Australia - Educational Programme in the Northern Territory.” Canberra, 1916-1965. A406, E62/237. National Archives of Australia.

“Extension of Franchise to Aboriginal Natives of Australia [Original File Split into Three Parts].” Canberra, 1962-1965. A406, E1962/237 B. National Archives of Australia.

Goot, Murray. “The Aboriginal Franchise and Its Consequences.” Australian Journal of Politics & History 52, no. 4 (December 1, 2006): 517–61.

Grant, Kirsty. “Thake, Eric Prentice Anchor (1904–1982).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Hawken, Noel, “Our Democracy Goes On Location”, The Herald, September 6, (1962):4

Hooper, Carole. “Rosenthal, Newman Hirsh (1898–1986).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Jaensch, Dean, and P. (Peter) Loveday, eds. Under One Flag : The 1980 Northern Territory Election / Edited by D. Jaensch and P. Loveday. Sydney ; Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1981.

Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters. “Inquiry into Civics and Electoral Education,” 2007.

Loveday, P. “The Australian Aboriginal Electoral Information Service.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 47, no. 4 (December 1, 1988): 343–50.

Loveday, P. (Peter), A. Randall, Will Sanders, and Dean Jaensch. The Aboriginal Electoral Information Service : Report of the Review 1987-88. Australian National University. North Australia Research Unit, 1988.

Noonuccal, Oodgeroo (Kath Walker) 1929–1993.

In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.Reid, Margaret. “Caste-Ing the Vote: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voting Rights in Queensland.” Hecate 30, no. 2 (2004): 71-80.

Report from the Select Committee on Voting Rights of Aborigines. Commonwealth Government Printer, 1961.

Rutledge, Martha. “O’Connor, Richard Edward (Dick) (1851–1912).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Sanders, Will. “Delivering Democracy to Indigenous Australians.” In Elections : Full, Free & Fair, edited by Marian Sawer. Annandale, N.S.W: Federation Press, 2001.

Stretton, Pat, and Christine Finnimore. “Black Fellow Citizens: Aborigines and the Commonwealth Franchise.” Australian Historical Studies 25, no. 101 (October 1, 1993): 521–35.

Stringer, Ernest. An Evaluation of the Aboriginal Electoral Education Programme. Perth, WA: Western Australian Institute of Technology, 1983.