'We hereby make protest'

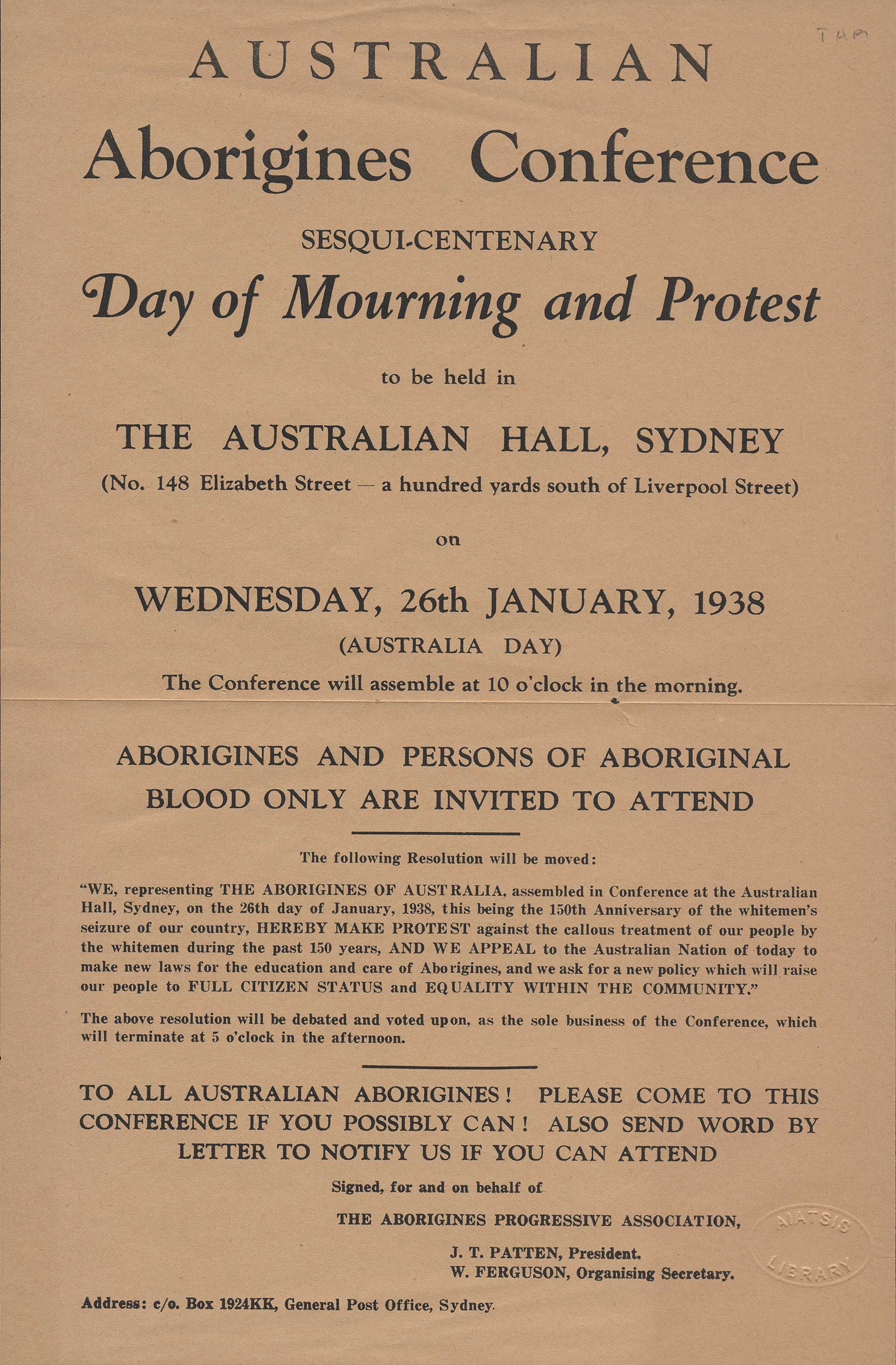

On January 26 1938, while many Australians celebrated the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet, a group of Aboriginal men and women gathered at Australia Hall in Sydney. They had come together to continue a struggle that had begun 150 years previously. They met to move the following resolution:

‘WE, representing THE ABORIGINES OF AUSTRALIA, assembled in conference at the Australian Hall, Sydney, on the 26th day of January, 1938, this being the 150th Anniversary of the Whiteman's seizure of our country, HEREBY MAKE PROTEST against the callous treatment of our people by the whitemen during the past 150 years, AND WE APPEAL to the Australian nation of today to make new laws for the education and care of Aborigines, we ask for a new policy which will raise our people TO FULL CITIZEN STATUS and EQUALITY WITHIN THE COMMUNITY.’

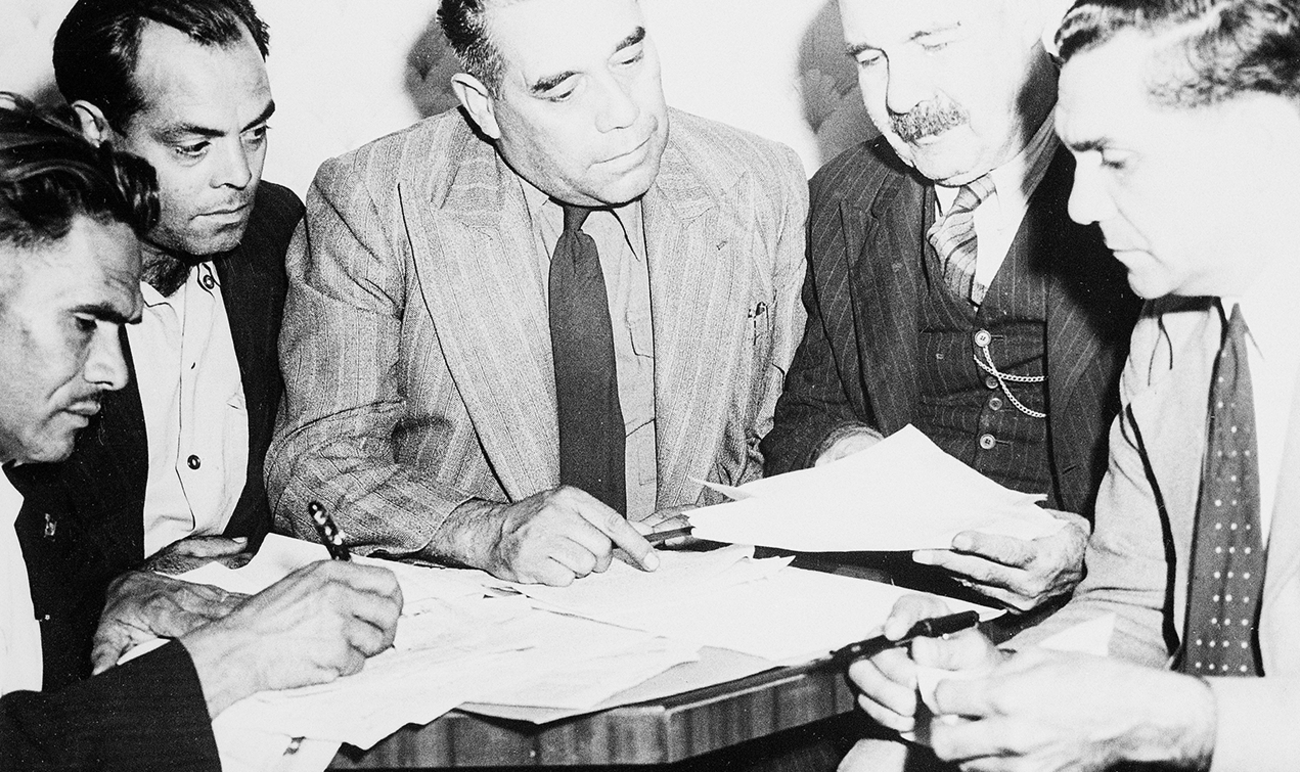

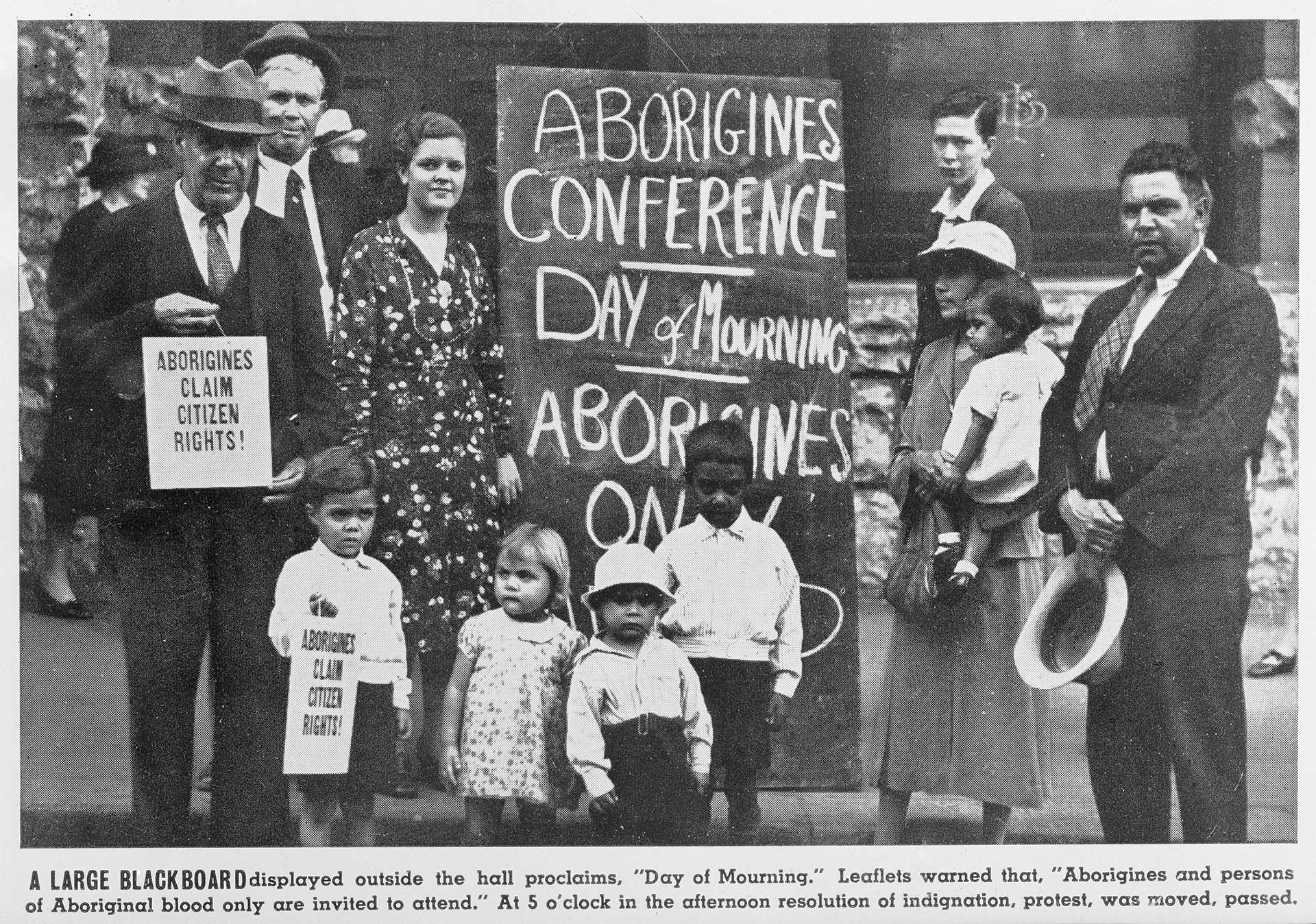

The first Day of Mourning. From the left is William Ferguson, Jack Kinchela, Isaac Ingram, Doris Williams, Esther Ingram, Arthur Williams, Phillip Ingram, Louisa Agnes Ingram OAM holding daughter Olive Ingram, and Jack Patton. The name of the person in the background to the right is not known at this stage. AIATSIS Collection HORNER2.J03.BW.

The first Day of Mourning. From the left is William Ferguson, Jack Kinchela, Isaac Ingram, Doris Williams, Esther Ingram, Arthur Williams, Phillip Ingram, Louisa Agnes Ingram OAM holding daughter Olive Ingram, and Jack Patton. The name of the person in the background to the right is not known at this stage. AIATSIS Collection HORNER2.J03.BW.

The first Day of Mourning was a culmination of years of work by the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) and the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA). It would became the inspiration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activism throughout the remainder of the twentieth century. In the early 1960s, both organisations would reform and reshape and become the driving force calling for a constitutional referendum that would take place in 1967.

The AAL was able to persuade many religious denominations to declare the Sunday before Australia Day as ‘Aboriginal Sunday’. This was to serve as a reminder of the unjust treatment of Indigenous people. The first of these took place in 1940 and continued until 1955, when it moved to the first Sunday in July.

In 1957, with support and cooperation from federal and state governments, the churches and major Indigenous organisations, a National Aborigines Day Observance Committee (NADOC) was formed, which continues to this day as NAIDOC.

The Australian Aborigines League

The Australian Aborigines League was established in 1932 by William Cooper, a Yorta Yorta man and leader, who at age 71 took on the role of Honorary Secretary. The AAL membership included other prominent Aboriginal activists such as Margaret Tucker, Eric Onus and Shadrach James

After seeking permission from the Board of Protectors, and with limited means available that would enable broad reach, William Cooper circulated a petition across Australia throughout 1933 and 1934. The petition called upon the government to improve living conditions for Aboriginal people and to enact legislation that would guarantee Aboriginal representation in Parliament.

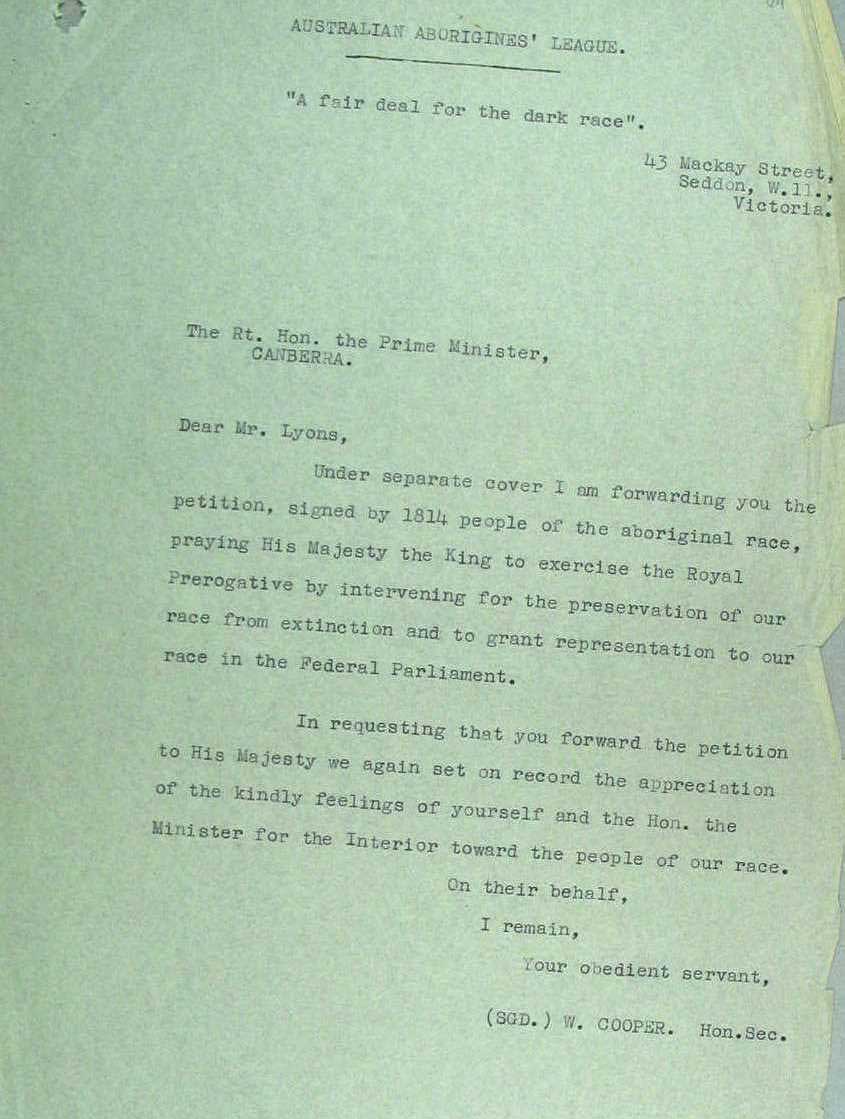

Cooper sent the petition to Prime Minister Joseph Lyons in an undated letter in August of 1937 in the hope that he would forward it to King George VI.

He wrote:

‘Dear Mr. Lyons, … I am forwarding you the petition, signed by 1814 people of the Aboriginal race, praying His Majesty the King to exercise the Royal Prerogative by intervening for the preservation of our race from extinction and to grant representation to our race in the Federal Parliament.’

While the government acknowledged receipt of the petition, they gave no indication that it would be forwarded to the King.

William Cooper’s correspondence to Prime Minister Joseph Lyons regarding the Petition to the King, ‘Representation of Aborigines in Commonwealth Parliament’. National Archives of Australia A431, 1949/1591, p.125.

William Cooper’s correspondence to Prime Minister Joseph Lyons regarding the Petition to the King, ‘Representation of Aborigines in Commonwealth Parliament’. National Archives of Australia A431, 1949/1591, p.125.

William Cooper’s correspondence to Prime Minister Joseph Lyons regarding the Petition to the King, ‘Representation of Aborigines in Commonwealth Parliament’. National Archives of Australia A431, 1949/1591, p.125.

The Aborigines Progressive Association

The Aborigines Progressive Association was launched in 1937 by William Ferguson and Jack Patten. The principal objectives of the APA were:

- To conduct propaganda for the emancipation and betterment of Aboriginal people.

- To take all steps which may be necessary to secure full citizen rights for Aboriginal people and repeal of restrictive legislation concerning Aboriginal people.

- To examine all proposals concerning Aboriginal people from the point of Aboriginal people themselves and to formulate policies to place before the governments of Australia for Aboriginal betterment.

In early 1937, Ferguson made a public call for a Parliamentary Select Committee enquiry into the administration of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board. The inquiry began in November of that year with Ferguson appearing before it as ‘a representative of the Aborigines of New South Wales’.

During the proceedings, Ferguson read out correspondence sent to the APA from Aboriginal people throughout New South Wales. These letters were scathing in their condemnation of the poor treatment of Aboriginal people by the Aborigines Protection Board.

Pastor Frank Roberts, a Bundjalung man from Tuncester, wrote:

‘It is terrible. Words cannot express what is scandalous treatment by the Destruction Board…The Aborigines Protection Board made conditions so hard that I was forced to leave the settlement , and through persecution of the board…I am without a home’.[i]

We are eagles

On November 12 1937, William Cooper called a meeting of leading Aboriginal activists. Among the attendees were Doug Nicholls and William Ferguson.

The following day, details of the event were published on the front page of the Melbourne newspaper The Argus. At the meeting Cooper called for a Day of Mourning and protest in Sydney to be held on the following 26 of January.

‘Plans for the observance of aborigine's throughout Australia of a 'Day of mourning' simultaneously with the 150th anniversary celebrations in Sydney, were announced by the Australian Aborigines League.

‘“While white men are throwing their hats in the air with joy”, said the chairman (Mr A.P.A. Burdeu), “aborigines will be in mourning for all that they have lost.” It was hoped, Mr Burdeu added, that the Day of mourning would direct the attention of the people of Australia to the desire of the aborigines for full rights of citizenship.

‘Stating that he was proud of his aboriginal blood, Mr William Ferguson said that the aborigines did not want protection.

"We have been 'protected' for 150 years, and look what has become of us."

‘Mr Ferguson complained bitterly of the treatment of aborigines at aboriginal settlements in NSW. “It would be better for the authorities to turn a machine-gun on us,” he said.

‘Mr Douglas Nicholls,... said that aborigines were not satisfied merely to be kept alive by a weekly issue of rations. “We do not want chicken food,” he said. “We are not chickens; we are eagles."’

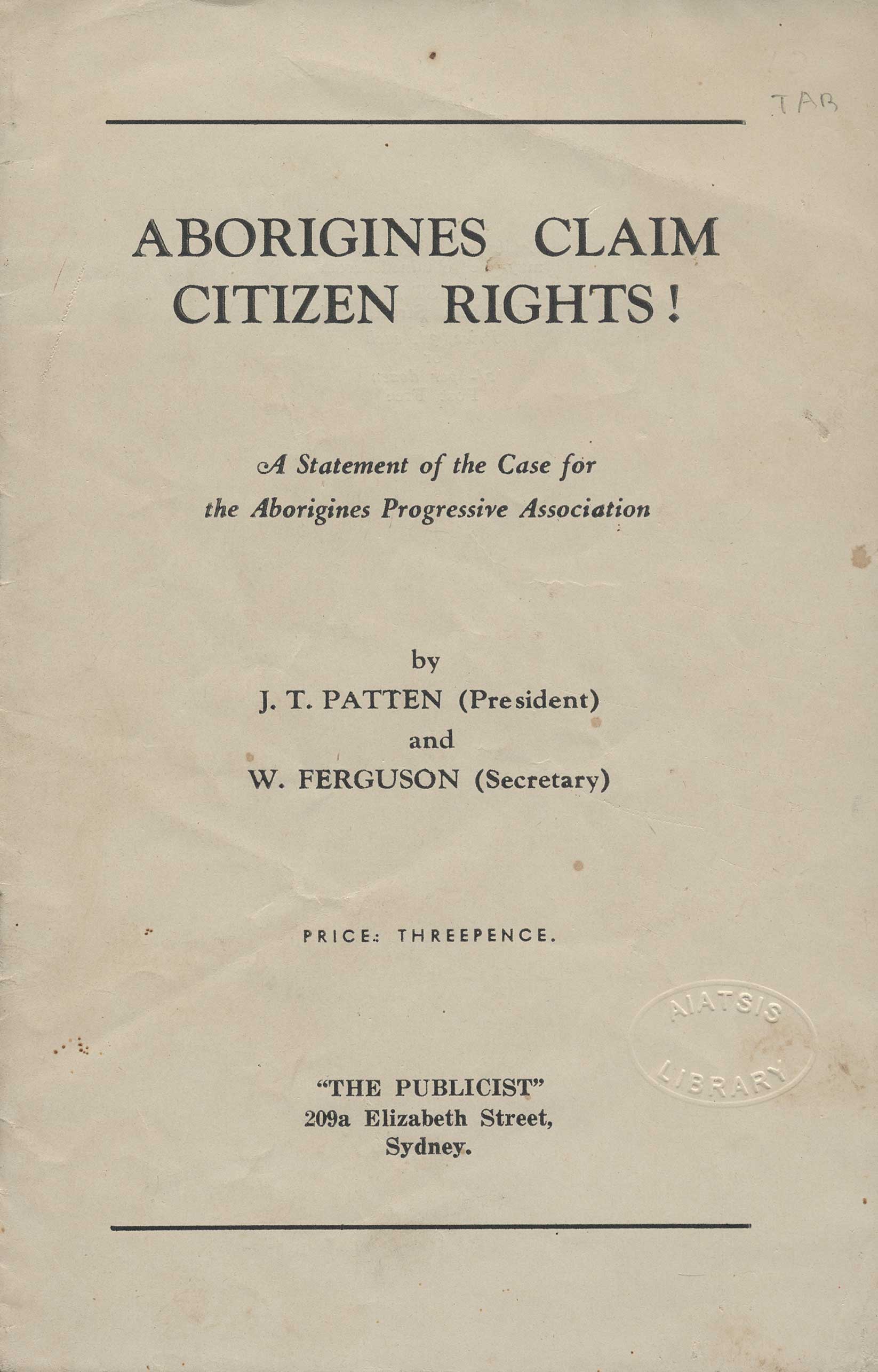

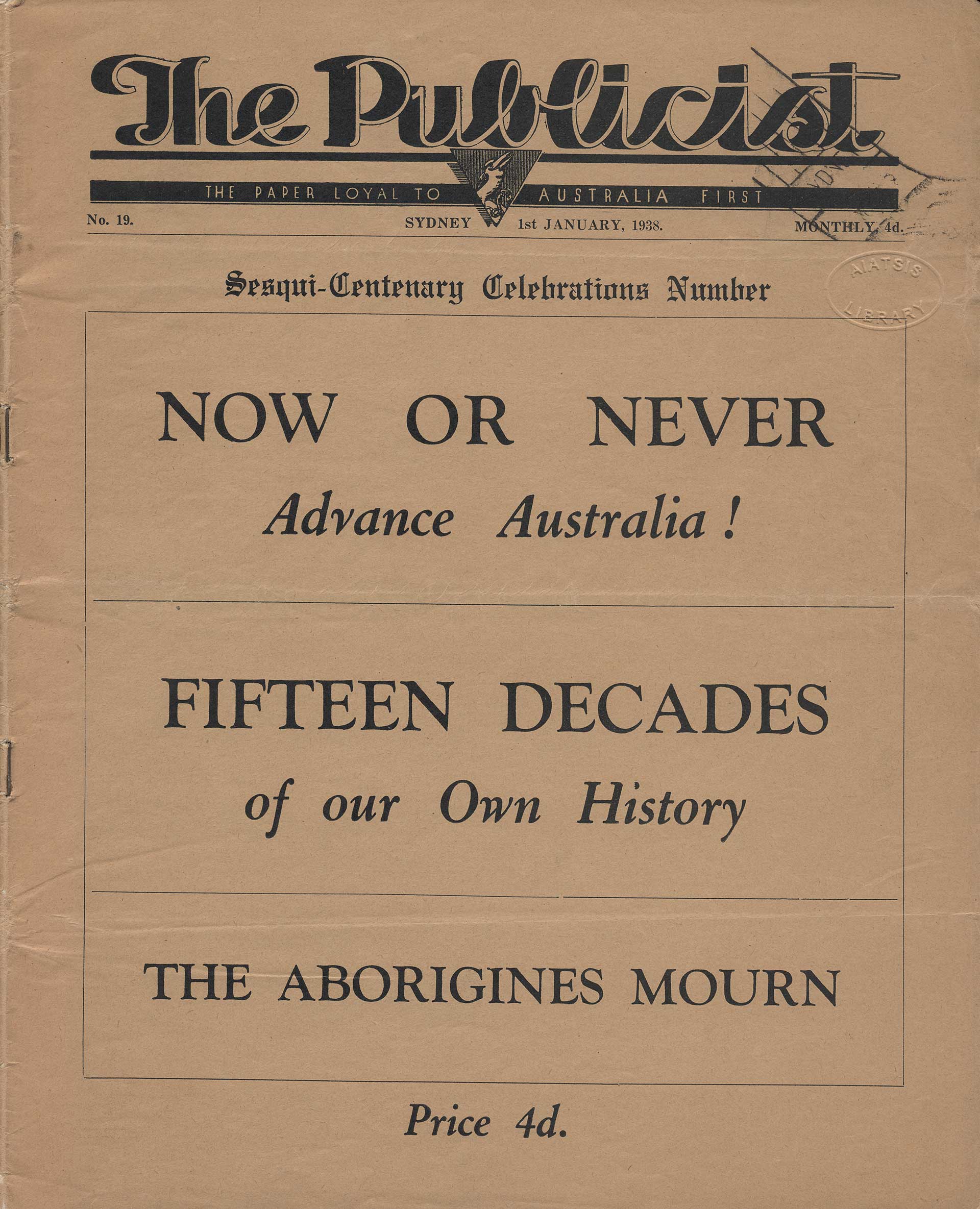

In early January of 1938, Jack Patten and William Ferguson published the pamphlet titled Aborigines Claim Citizens Rights. The pamphlet described the conditions for Aboriginal people in Australia from their own perspective. It was published with the assistance of PR Stephensen, who also published the material in his own magazine The Publicists, and would later facilitate the publication of The Australian Abo Call.

One hundred and fifty years of so called ‘progress’

‘The 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.

‘We, representing the Aborigines, now ask you, the reader of this appeal, to pause in the midst of your sesqui-centenary rejoicings and ask yourself honestly whether your “conscience” is clear in regard to the treatment of the Australian blacks by the Australian whites during the period of 150 years’ history which you celebrate?’[ii]

‘We are the old Australians’

‘You are the New Australians, but we are the Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the Original Australians, who have lived in this land for many thousands of years.'

‘You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation’.[iii]

In a prime time interview on radio station 2SM in Sydney, Jack Patten informed listeners that:

‘…the time has come now, after one hundred and fifty years of so-called progress, for the white people of Australia to face up to their responsibilities…we now ask for freedom and equal citizenship. Our only hope of obtaining justice is to arouse the conscience of the white people of Australia, and to make them realise how lacking they have been in regard to accepting their responsibilities towards us, the original owners of the land.’[iv]

The stage was set for Aboriginal people from across Australia to gather in Sydney to highlight the plight of their people and to call for a better deal.

Surely the time has come

On January 26 1938, Sydney awoke to a warm, sunny day. A series of events and activities had been organised to mark the sesquicentenary anniversary.

For those who celebrated, there was a parade, a sailing regatta and a lawn bowls tournament. One of the feature events of the day was a re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet. A group of Aboriginal men from Menindee, in far-west New South Wales, were brought to Sydney to act in the role of the original Eora peoples of Port Jackson.

Those who mourned and had little reason to celebrate were kept waiting until the parade passed by. Only then could they march in silent protest from Town Hall to Australian Hall in Elizabeth Street. Once they arrived, the protestors were required to use the back entrance to access the building. On that hot January day, members of the APA wore formal black dress as a symbolic sign of mourning.

First national meeting of Aboriginal people for citizenship rights

With the sesquicentenary parade delaying the marchers, the meeting did not start until 1.30 that afternoon. Jack Patten chaired the meeting and was joined on stage by Bill Ferguson, Doug Nicholls, William Cooper and Jack Kinchela.

About a hundred people attended including Margaret Tucker, Selina Patten (Jack’s wife), Pearl Gibbs, Jack Johnson, Mrs F. Ardler, Bert Marr, Frank Roberts, Tom Peckham, Henry Noble, Jack Kinchella, Bert Groves, Ted Duncan, Robert McKenzie, Louisa Agnes Ingram, Doris Williams and Tom Foster. Helen Grosvenor served as minute taker.

Only four non-aboriginal people were allowed to attend; two policemen as well as Russell Clark from Man magazine and PR Stephensen.

Jack Patten was the first speaker:

‘On this day the white people are rejoicing, but we, as Aborigines, have no reason to rejoice on Australia's 150th birthday. Our purpose in meeting today is to bring home to the white people of Australia the frightful conditions in which the native Aborigines of this continent live.

‘This land belonged to our forefathers 150 years ago, but today we are pushed further and further into the background. The Aborigines Progressive Association has been formed to put before the white people the fact that Aborigines throughout Australia are literally being starved to death.

‘We refuse to be pushed into the background. We have decided to make ourselves heard. White men pretend that the Australian Aboriginal is a low type, who cannot be bettered. Our reply to that is, "Give us the chance!" We do not wish to be left behind in Australia's march to progress. We ask for full citizen rights..."[v]

William Ferguson was the next speaker to rise:

‘We have been waiting and waiting all our lives for the white people of Australia to better our conditions, but we have waited in vain. We have been living in a fool's paradise.

‘I have travelled outback and I have seen for myself the dreadful sufferings of our people on the Aborigines Reserves…Surely the time has come at last for us to do something for ourselves, and make ourselves heard. This is why the Aborigines Progressive Association has been formed.’[vi]

Dough Nichols spoke on behalf of the Aboriginal people of Victoria:

‘...I want say that we support this resolution in every way. The public does not realise what our people have suffered for 150 years.

‘Aboriginal girls have been sent to Government Reserves and have not been given any opportunity to improve themselves. Their treatment has been disgusting. The white people have nothing for us whatever… Now is our chance to have things altered. We must fight our very hardest in this cause.’[vii]

Mr Connelly, from the south coast of New South Wales highlighted the dispossession suffered by his people:

‘In 150 years the white men have taken away the hunting grounds and camping grounds of our people, and left us with nothing. We must have unity among ourselves or we will not succeed in the uplifting of our race. …

‘On behalf of the Aborigines of the South Coast, I want to thank the men who have started this great movement of Aborigines Progress. If we are to succeed we must be united. Let us fight on to a successful end.’[viii]

Pearl Gibbs was the last speaker of the day and recalled with passion her meeting with some of the Aboriginal elders:

‘Conditions on all the Aboriginal stations are a disgrace. They are all very much alike. At Brewarrina the children are taught by a man who is not a qualified teacher. Two old men on that station, one blind, the other a cripple, are left by themselves in a half-starved state. I spoke to these old men, and when they told me how badly they were treated it made me cry, and pray that this movement will be a success.’

The last item on the agenda for the day was the election of office bearers. Jack Patten was returned as president, Helen Grosvenor was elected secretary, William Ferguson was re-elected organising secretary and Jack Kinchela became treasurer.

This ended the first national meeting of Aboriginal people for citizenship rights. The protest and conference received some coverage in the national press with many newspapers giving grudging acknowledgement to the grievances and concerns aired at the meeting.

Although the gathering held on 26 January in 1938 brought about little actual change at the time, it was a turning point in the evolution of a national struggle by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to gain the same rights as those held by all other Australians.

Beyond the Day of Mourning

The following week, on 31 January 1938, a deputation of about 20 people met with the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, his wife Enid as well as the Minister for the Interior, John McEwen (whose Department held responsibility for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory), to present a proposed national policy for Aboriginal people. Among the deputation were John Patten, William Ferguson, Mrs D Anderson, Helen Grosvenor, Pearl Gibbs and her mother, and Tom Foster.

They called for Commonwealth control of all Aboriginal matters, with a separate Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs; an administration advised by a board of six, at least three of whom were to be Aboriginal people nominated by the Aborigines Progressive Association; and full citizen status for all Aboriginal people and civil equality with white Australians, including equality in education, labour laws, workers compensation, pensions, land ownership and wages. Lyons replied that, under the Constitution, Commonwealth control was not possible.

In early February, Pearl Gibbs addressed a meeting of the Housewives’ Progressive Association:

‘You white people awoke on Anniversary Day with a feeling of pride at what you had done…but did you not think of the Aborigine’s broken hearts, and that for them it was a day of mourning?

‘What has any white man or woman done in this country to help my people, the Aborigines? The Aborigines are now taking up the matter for themselves and asking for citizenship. It is not ridiculous or silly for them to ask for citizenship in a country that is their own.’[ix]

Three months after the Day of Mourning the first issue of The Australian Abo Call appeared on newsstands. Edited by Jack Patten, the publication proclaimed itself the ‘the voice of the Aborigines’ and continued to demand for rights and equality for Aboriginal people. The first issue noted that:

‘The Abo Call is our own paper. It has been established to present the case for [A]borigines, from the point of view of the Aborigines themselves.’

The Australian Abo Call reported on the poor living conditions faced by many Aboriginal people and attempted to dispel the notion of peaceful European colonisation. Unfortunately, the publication was short-lived and only lasted for six issues from April to September 1938.

The Day of Mourning protest did succeed in raising some awareness about the conditions faced by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

As one correspondent to The Katoomba Daily noted:

‘Excessive self-glorification, unaccompanied by any self-examination of our many past follies and injustices, does not evince a high degree of moral development... The past cannot be undone, but let us not continue to withhold justice.’[x]

In November 1940 William Cooper retired as Honorary Secretary of the Australian Aborigines League. Sadly he passed away in 1941. The AAL continued under the guiding hand of Doug Nicholl and Bill Onus. In the 1960s the organisation changed its name to the Aborigines Advancement League.

The Aborigines Progressive Association remained active until 1944. However, political differences between William Ferguson and Jack Patten led to an internal split in the organisation shortly after the events of January 26.

Despite the split both factions continued the struggle for equal rights for Aboriginal people. The APA was revived in the early 1960s by Bert Groves and Pearl Gibbs. Many of its members would be instrumental in advocating for the 1967 Referendum.

Further reading

Books

Aborigines Advancement League (Victoria), Victims or Victors: The Story of the Aborigines Advancement League , South Yarra, Vic, Hyland House, 1985.

Attwood, Bain, Rights for Aborigines, Crows Nest, N.S.W. : Allen & Unwin, 2003.

Attwood, Bain, and Markus, Andrew, The struggle for Aboriginal rights: a documentary history, NSW, Allen and Unwin, 1999.

Attwood, Bain and Marcus, Andrew, Thinking Black: William Cooper and Australian Aborigines' League, Canberra, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2004.

Broome, Richard, Aboriginal Victorians: a history since 1800, Crows Nest, N.S.W. : Allen & Unwin, 2005.

Clark, Mavis Thopre, The boy from Cumeroogunga, Sydney : Hodder & Stoughton, 1979.

Cooper, William, Blood from a stone : William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines League / edited, with an introduction by Andrew Markus, Clayton, Vic.:Monash Publications in History, 1986.

Gammage, Bill and Spearitt,Peter, eds, Australians 1938, Sydney, Farfax, Syme and Weldon Associates, 1987.

Goodall, Heather, Invasion to Embassy : Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770-1972, Sydney University Press, 2008.

Horner, Jack, Bill Ferguson : fighter for Aboriginal freedom / a biography by Jack Horner, Dickson, A.C.T.:Jack Horner, 1994.

Horner, Jack, Vote Ferguson for Aboriginal freedom, Australian and New Zealand Book Co. 1974.

Heiss, Anita, ed., Life in Gadigal country, Marrickville, N.S.W. : Gadigal Information Service Aboriginal Corporation, 2002.

Maynard, John. Fight for Liberty and Freedom : The Origins of Australian Aboriginal Activism. Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007.

Manuscripts

MS 1515 (finding aid) Gribble, E.R.B. (Ernest Richard Bulmer), 1869-1957, Collected papers, 1892-1970.

MS 2022 Horner, Jack, Aboriginal social and political affairs of 1938, especially the Day of Mourning meeting, January 1938 and the Prime Ministers deputation.

MS 4112 (finding aid) Horner, Jack, Jack Horner's research notebooks on the life and times of Bill Ferguson.

MS 2368 (finding aid) Pink, Olive, Papers of Olive Muriel Pink.

Select Committee on Administration of Aborigines Protection Board: Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence and Exhibits. Sydney: Legislative Assembly of New South Wales, 1938

Rare pamphlets and serials

Aborigines Progressive Association, Australian Aborigines Conference sesqui-centenary day of mourning and protest to be held in the Australian Hall, Sydney, 1938.

Patten, J.T. and Ferguson, W., Aborigines claim citizen rights! : a statement of the case for the Aborigines Progressive Association, Sydney: The Publicist, 1938.

The Australian Abo call: the voice of the Aborigines.

Articles and book chapters

Aborigines meet, mourn while white-man nation celebrates, Man Magazine, March 1938, pp. 84-85.

Aborigines petition the King – 1937, Churinga, Vol. 1, no. 12 May 1970, pp. 27- 35.

Horner, Jack and Langton, Marcia, The Day of Mourning, p. 28-35, in Bill Gammage and Peter Spearitt (eds), Australians 1938, Fairfax, Syme and Weldon, Broadway, 1987.

Markus, Andrew, William Cooper and the 1937 petition to the King, in ‘Aboriginal History’ Vol. 7 no. 1. 1983 pp. 46-60.

McGregor, Russell, Protest and Progress: Aboriginal Activism in the 1930s, in ‘Australian Historical Studies’ 25, no. 101 (October 1, 1993), pp. 555–68.

Maynard, John, Vision, Voice and Influence: The Rise of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association, in ‘Australian Historical Studies’ 34, no. 121 (April 1, 2003), pp. 91–105.

Microforms

MF 311, Papers, 1936-1942 [microform]: re Aborigines Citizenship Committee and Aborigines Progressive Association, together with records of The Publicist Publishing Co. / Percy Reginald Stephensen.

References

[i] Select Committee on Administration of Aborigines Protection Board ‘Proceedings of the Committee Minutes of Evidence and Exhibits’. Sydney: Legislative Assembly of New South Wales, 1938, p. 55.

[ii] ‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights!: A Statement of the Case for the Aborigines Progressive Association’, the Publicist, 1938, p. 3.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Stephensen, PR (Percy Reginald). Papers, 1936-1942 Re Aborigines Citizenship Committee and Aborigines Progressive Association together with records of the Publicist Publishing Co. W & F Pascoe, 1936.

[v] ‘Our historic Day of Mourning and protest’, the Australian Abo Call, No. 1, April 1938, p. 2.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.