Dare I speak to oppressed and oppressor in the same voice? Dare I speak to you in a language that will move beyond the boundaries of domination - a language, that will not bind you, fence you in, or hold you? Language is also a place of struggle. The oppressed struggle in language to recover ourselves, to reconcile, to reunite, to renew.

Our words are not without meaning, they are an action, a resistance. Language is also a place of struggle.

bell hooks

Standard Australian English (AusE) is the language used in law, media, politics, and education in Australia, holding vast power. Over the years, many Indigenous people have been forced to speak AusE at the expense of ancestral language, Kriol, or Aboriginal English (AbE). Language bias, although largely implicit, is just as powerful and forces Aboriginal people to navigate linguistic imperialism daily.

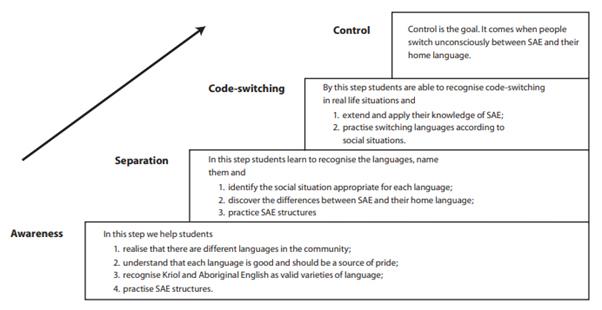

While we can choose to speak AbE to power, there may also be times when Indigenous people need to codeswitch into AusE. Control over codeswitching helps us to walk in the gudiya’s (non-Indigenous) world while maintaining home language and all the richness and connections that come with it (Berry & Hudson, 1997).

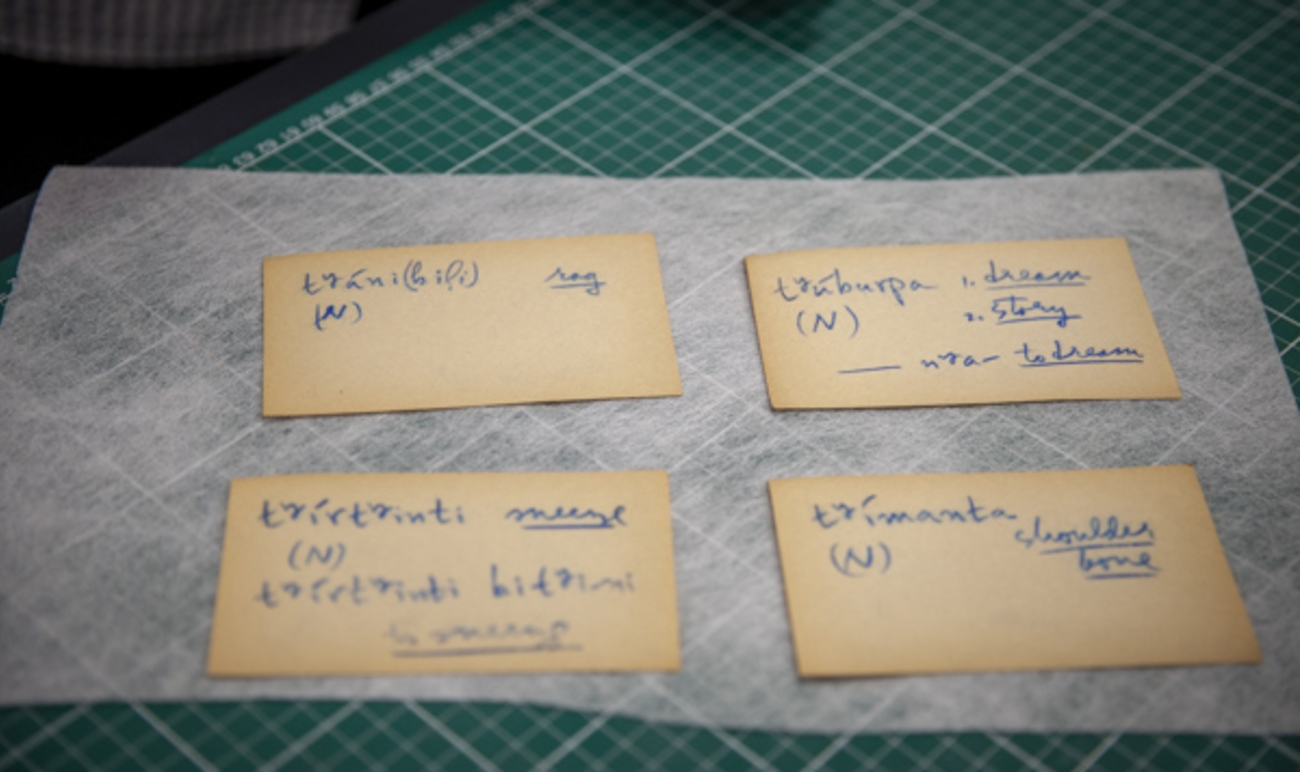

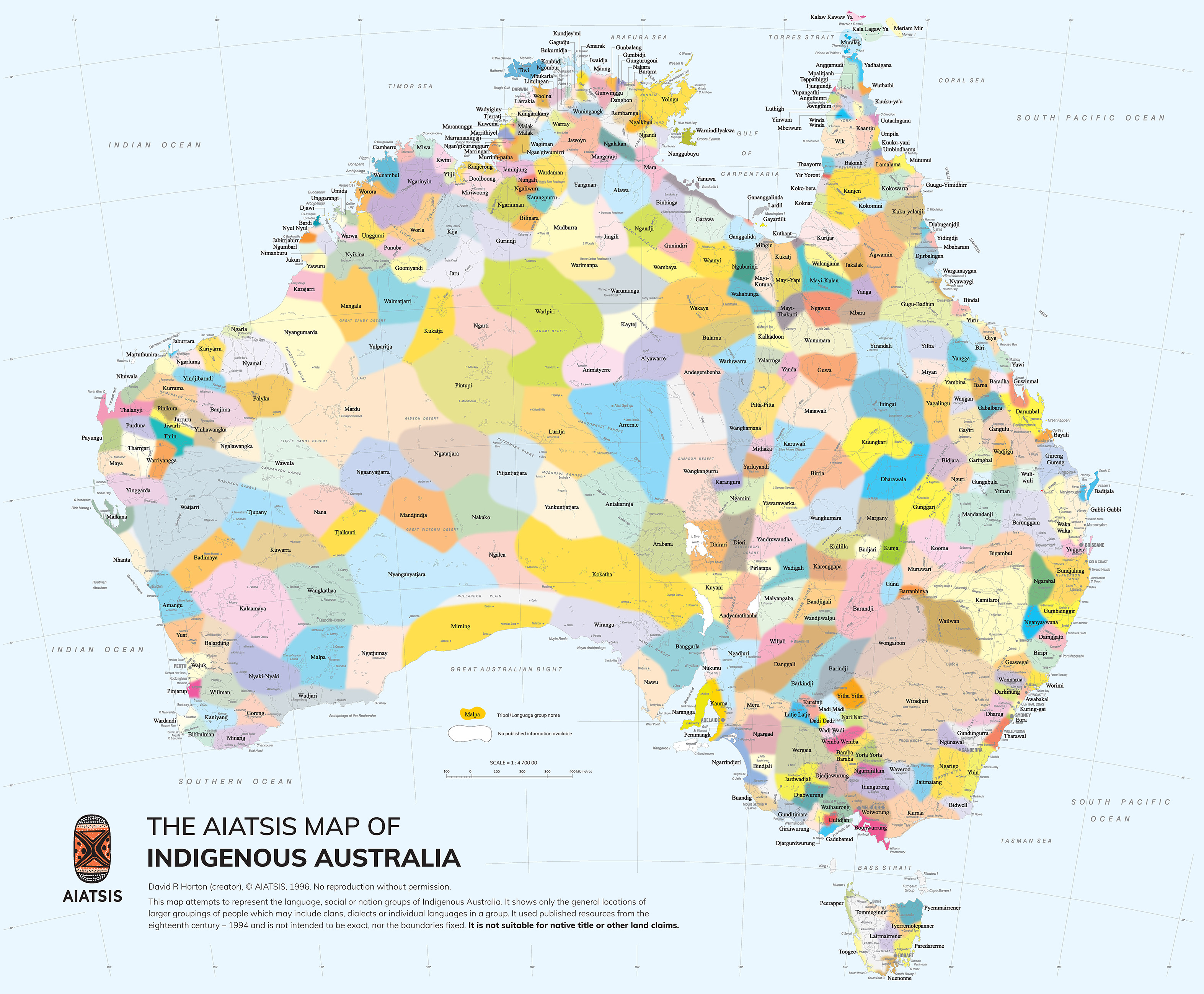

When colonisation began, it’s estimated that there were over 250 distinct languages plus around 600-800 overlapping, connecting Aboriginal language varieties (Blake, 1981, pp. 5‐6; The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 1994). Given that most settlers weren’t that keen to learn our languages, Aboriginal people adapted English to enable communication. With our ancestral Aboriginal languages stolen, along with our land, and being the adaptive and highly intelligent people that we are, we took the way they talked (and forced us to talk) and decolonised it to suit our needs.

This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. It shows only the general locations of larger groupings of people which may include clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. It used published resources from the eighteenth century-1994 and is not intended to be exact, nor the boundaries fixed. It is not suitable for native title or other land claims. David R Horton (creator), © AIATSIS, 1996. No reproduction without permission. Learn more.

This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. It shows only the general locations of larger groupings of people which may include clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. It used published resources from the eighteenth century-1994 and is not intended to be exact, nor the boundaries fixed. It is not suitable for native title or other land claims. David R Horton (creator), © AIATSIS, 1996. No reproduction without permission. Learn more.

Ongoing colonisation continues to have a detrimental effect on the survival of many ancestral Aboriginal languages and has influenced the development of new Aboriginal languages, creoles and AbE dialects (Berry & Hudson, 1997). Education policies have repressed Indigenous language and culture, ranging from denial, to segregation, then assimilation and onwards to integration (Beresford, Partington & Gower, 2012). Edwards (2004, p.6) stated that the 'social, political and economic pressures to abandon traditional languages was enormous, and the fact that languages survived at all is a remarkable testimony to the cultural integrity of these peoples.' Indigenous language and cultural practices were discouraged and often forbidden in classrooms until the 1970s with policies designed to assimilate Aboriginal culture and language into conventional society.

As such, many Indigenous people today speak AbE as a first, and in many cases only, language (Butcher, 2008). Although Indigenised varieties of English have been recognised by linguistics and some educators since the 1960s, unfortunately AbE is still considered ‘broken’ or ‘bad English’, or ‘slang’ talk today (Eades, 2013, p.88; Sharifian, 2011, p.52).

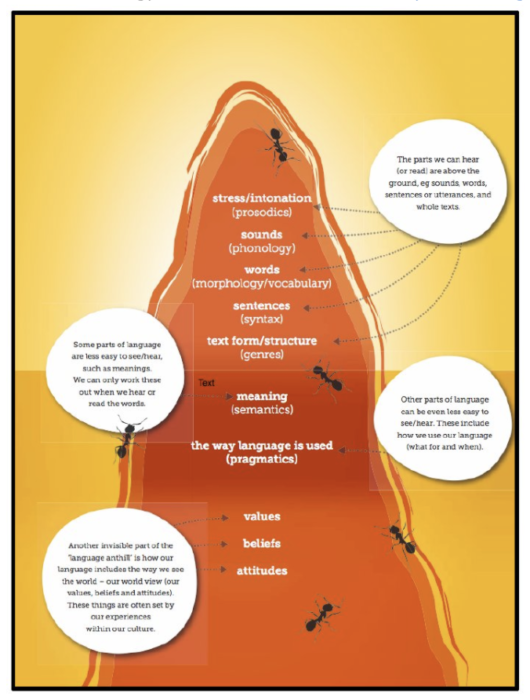

AbE is the name given to complex, rule-governed varieties of English that are spoken by over 80 per cent of Indigenous peoples across Australia (Partington and Galloway, 2007). AbE is not a form of AusE, but rather both are varieties of English. AbE differs from standard AusE in systematic ways and at all levels of linguistic structure, like sentence formation and meanings of words. AbE is mutually intelligible between varieties and can also be known by its local names, such as Koori or Murri English, Broome lingo and Noongar English. AusE speakers may also think they understand AbE, however there are many different layers and some of these cannot be seen or heard, such as pragmatics, semantics and worldview that includes values, beliefs and attitudes (Department of Education, Western Australia & Department of Training and Workforce Development, 2012).

Kriol is sometimes confused with AbE. It is a specific creole and a new Aboriginal language that is spoken across northern Australia that developed largely because of colonisation and the expansion of the pastoral industry (Dickson, 2016). So, while non-AbE speakers may be able to pick up what’s being said in conversations with AbE speakers, it is less likely with in Kriol due to the inclusion of more ancestral language words.

What makes AbE really cool and different from many ancestral languages and Kriol is that is it not officially taught (in a Western sense). It is a community-developed language that belongs to community. Being a marker of Aboriginal identity, it is confusing and offensive for non-Indigenous people to randomly pick up AbE and start talking. Imagine you are in the US, and you walk up to a group of African American people and started speaking Black American English (African American Vernacular English). You would soon be put in your place; same goes here. A rule of thumb… Just don’t. It’s shame.

Negative attitudes towards AbE risk the lives and livelihoods of Aboriginal people every day. Many Aboriginal people have been left without interpreters when dealing with police, health providers and in educational settings. The misinterpretation of AbE can lead to incarceration, misdiagnosis, and lead to low (standardised) education outcomes (Eades, 2004). What’s most frustrating is that systems continue to ignore the important role that understanding AbE has in all these areas that impact social determinants of health. By excluding AbE from reports, strategies and policies, the powers that be are denying the legitimacy of our connection to community, culture, and our identity and are contributing to our ongoing oppression.

AbE has been officially recognised as a legitimate language since the 1960s, so why is it still treated as slang or something less than?

The land gave birth to our ancestral languages; language and culture are inseparable. And yet, languages have been and continue to be stolen, with all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages currently under threat. So, it is essential we retain and revitalise our languages everywhere we can. And this also means we need to do some myth-busting and stop positioning AbE or Kriol as bad English.

Sharon Davis is from both Bardi and Kija peoples, is teacher trained and has a Master of Applied Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition from the University of Oxford. Sharon is the Director of Education and Ethics at AIATSIS.

Take our Aboriginal English quiz!

References

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (1994). Map of Indigenous Australia.

- Blake, B. (1981). Australian Aboriginal languages. Sydney, NSW., Australia: Angus & Robertson.

- Beresford, Q., Partington, G., & Gower, G. (2012). Reform and Resistance in Aboriginal Education: Fully revised edition. Crawley, WA., Australia: UWA Publishing.

- Berry, R. & Hudson, J. (1997), Making the jump: A resource book for teachers of Aboriginal students, W.A: Kimberley Region Catholic Education Office

- Butcher, A. (2008). Linguistic aspects of Australian Aboriginal English. Clinical linguistics & phonetics, 22(8), 625-‐642.doi:10.1080/02699200802223535

- Department of Education, Western Australia & Department of Training and Workforce Development). (2012). Tracks to Two‐Way Learning: Understanding language and dialect.

- Dickson, G. (2016). Explainer: the largest language spoken exclusively in Australia – Kriol.

- Eades, D. (2004). Understanding Aboriginal English in the legal system: A critical sociolinguistics approach. Applied linguistics, 25(4), 491‐512. DOI: 10.1093/applin/25.4.491

- Eades, D. (2013). Aboriginal Ways of Using English. Canberra, ACT, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Edwards, V. (2004). Multilingualism in the English‐speaking world: Pedigree of nations. Malden, MA: Wiley-‐Blackwell Publishing.

- Partington, G. and Galloway. A. (2007). Issues and policies in school education. In Gerhard Leitner and Ian G. Malcolm (eds.), The Habitat of Australia’s Aboriginal Languages: Past, Present and Future (237–66). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Sharifian, F. (2011). Cultural conceptualisations and language: Theoretical framework and applications. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Co.