The early years

In 1909, aged nine Jimmie Barker found himself at ‘Milroy,’ a sheep station with a rich history of Aboriginal cultural contact. Jimmie and his younger brother Billy had moved across from Mundiwa, an Aboriginal reservation on the Culgoa River, after their mother Maggie found employment here.

The move was part of a broader movement of Aboriginal people in northwest NSW which lasted from 1907 to the 1930s. In Jimmie’s unpublished autobiography Days Night and Day, he recalls this whirlpool of displacement, describing how people moved from “town to town” like never before.

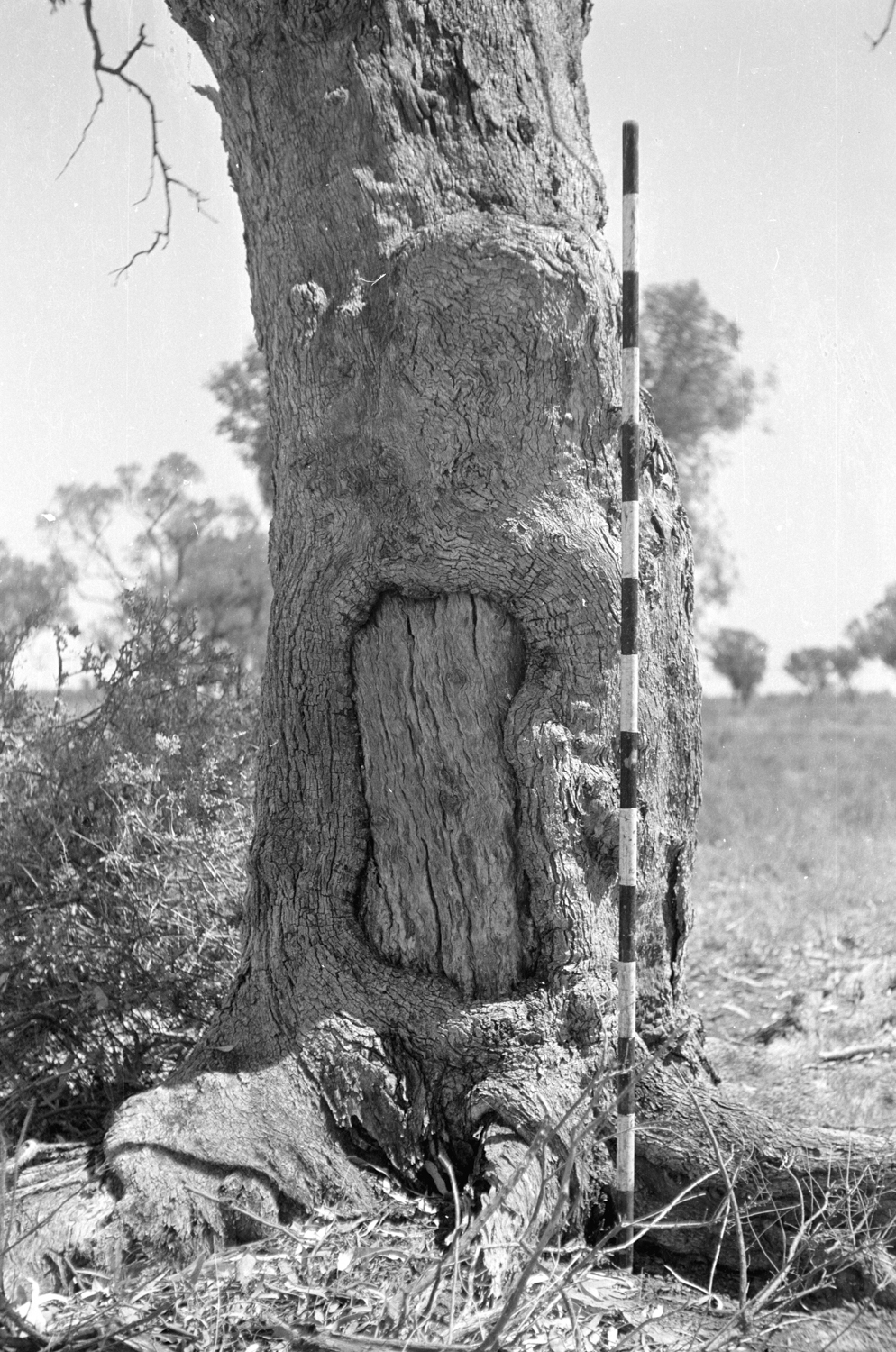

As their time at Mundiwa drew to a close, Jimmie and Billy marked trees with a Dhowin (tomahawk) and buried personal artefacts beneath them in “old style pickle bottles”.

Jimmie describes his dread at the prospect of moving away from Mundiwa – a dread born of the deep sense of family and community he’d experienced at the reservation and his fear of separation from the “old people”.

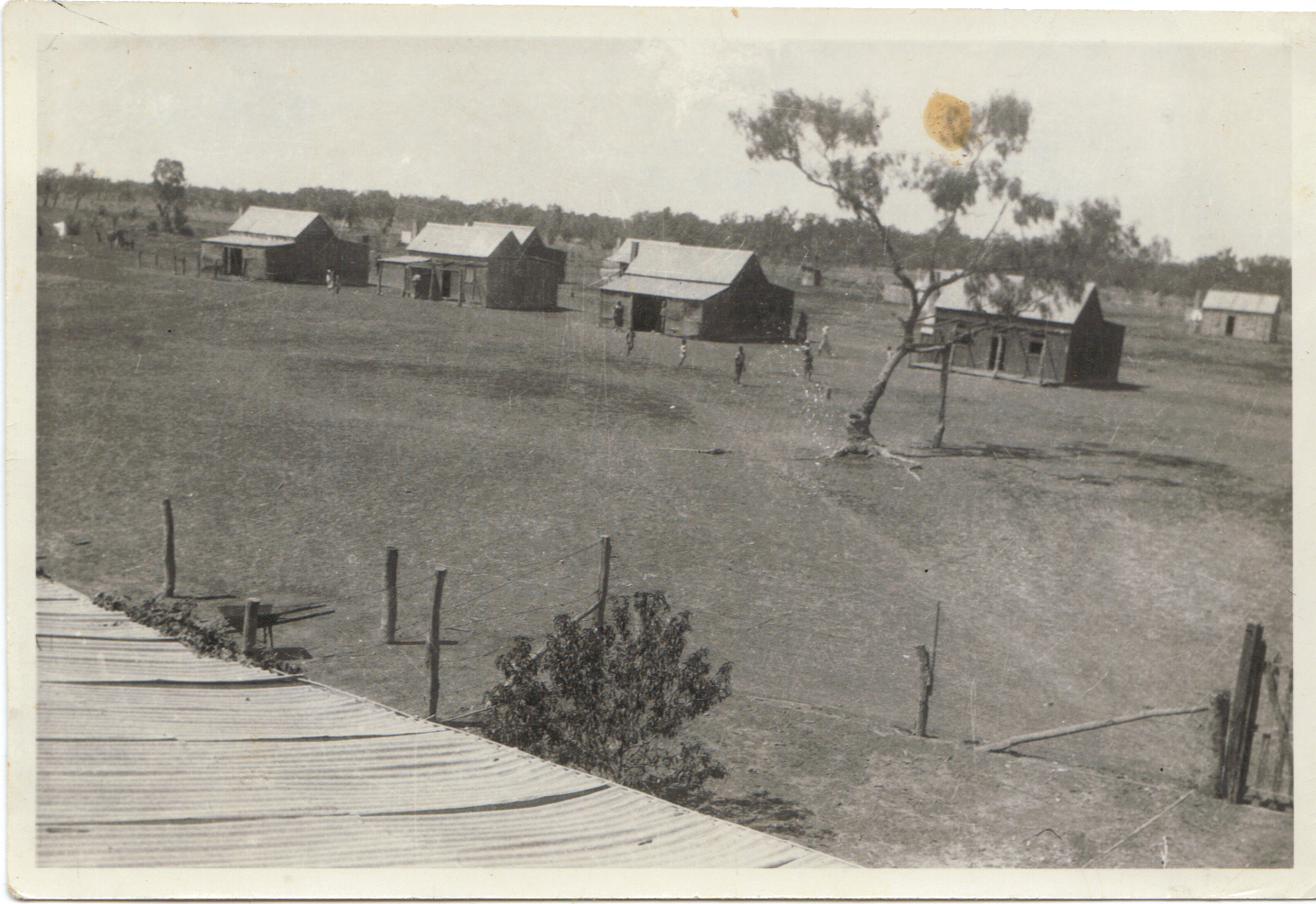

Outstation building at Denewan, 1977

Photograph by Harry Creamer, AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_09A.

Outstation building at Denewan, 1977

Photograph by Harry Creamer, AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_09A.

Culgoa River Denewan, 1977

Photograph by Harry Creamer

AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_05A.

Culgoa River Denewan, 1977

Photograph by Harry Creamer

AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_05A.

Scar tree at Weilmoringle, 1977.

Photograph by Harry Creamer. AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_04A.

Scar tree at Weilmoringle, 1977.

Photograph by Harry Creamer. AIATSIS Collection, CREAMER.H05.BW-N10433_04A.

Jimmie speaks of seeking out, from a very young age, the company and mentorship of the “old people” – a pre-contact Muruwari generation born decades prior to settlement of the area. Through these elders, Jimmie immersed himself in Muruwari cultural practices he refers to as the “old ways” – first at Mundiwa, then at Milroy Station and later at Brewarrina Mission Station.

Mundiwa eventually dissolved. This was due to cultural factors rather than colonial or settler pressures; the death of community leader Jimmy Kerrigan meant those remaining at the reservation must leave.

Despite his misgivings about the move to Milroy, Jimmie was resilient and eventually came to enjoy life at the station. In fact, he described 1909 as “a wonderful year”.

Official records paint the experience of Aboriginal staff at Milroy as one of typical servitude. But Indigenous history reveals Milroy as a cultural hub.

The station is also the purported birthplace of Muruwari woman Emily Horneville, another great source of Muruwari language and cultural knowledge.

Jimmie took pleasure in some domestic duties at Milroy, particularly maintaining the garden of Mrs Armstrong, the mistress of the station. But by his account he and Billy enjoyed a level of freedom, which gave rise to an intense period of technological experimentation.

Jimmie’s first recorded experiment took place at Mundiwa; it involved half-filling a Holbrook sauce bottle with water and placing it on a fire. In Days Night and Day he describes the explosion and the beating that he received from his mother.

Undeterred, Jimmie established what he called his “laboratory,” a workshop of sorts. Key to this was his friendship with the station’s resident blacksmith Tommy, and perhaps more importantly a rubbish dump from which he drew components for his mechanical experiments.

Jimmie Barker’s early life coincided with some of the most rapid technological development in human history. The world was being transformed by the internal combustion engine, electricity and telecommunications.

Simultaneously, Jimmie began devising some of the same technologies being developed elsewhere, including sound recording and steam power. His inventions and discoveries were derived independently – as Jimmie states, “these were my ideas”.

Goorungu - of (or by) string

Jimmie Barker’s genius lies not just in his experiments and inventions, but in his ability to integrate traditional Indigenous knowledge when engaging with new technologies.

For example, Jimmie details the roll-out of telephone and telegraph infrastructure to Northwest NSW. He meticulously describes mile upon mile of wiring extending from post offices to station homesteads, shearing sheds and other station buildings. These incisive descriptions sit alongside expositions of traditional Muruwari modes of telepathic communication such as Goorungu, a Muruwari word meaning “like (or by) string”.

Jimmie recalls camping trips with the “old people” where a member of the party, would know a visitor was about to arrive, without having been forewarned. In another instance, he tells how one of the “old people” had a premonition of trouble at home. The camping trip was cut short and the group returned to find that an old woman at Brewarrina Mission, known to everyone as “Granny”, had died. “Granny” is also mentioned by Jimmie, in relation to his first experience of tobacco smoking at Mundiwa.

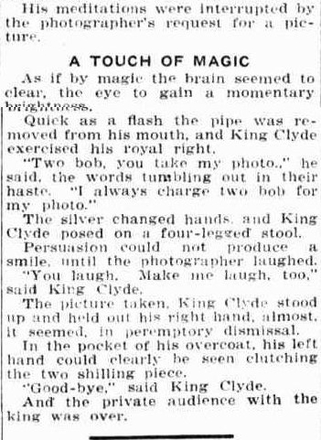

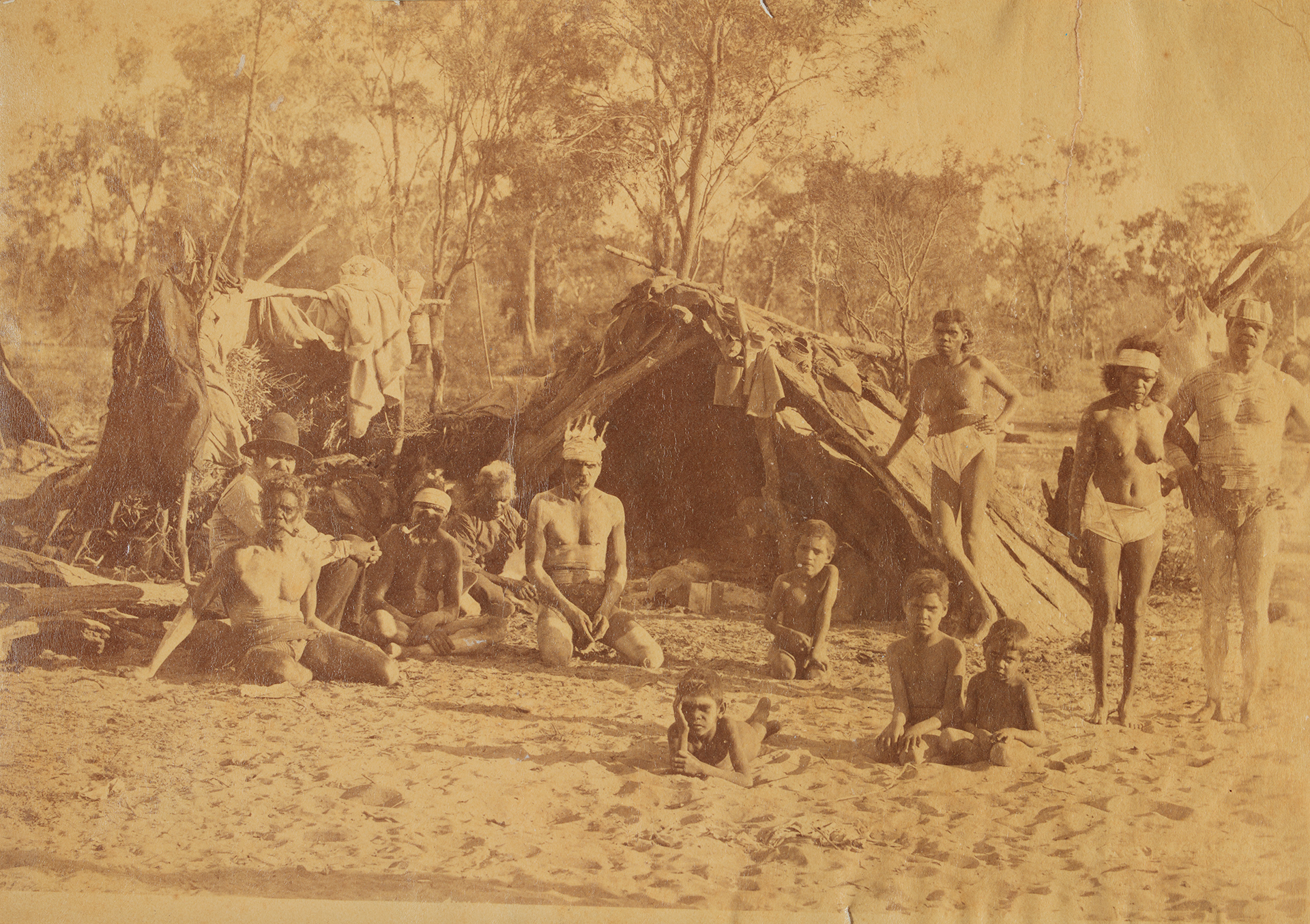

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (3 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (3 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (2 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (2 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (1 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Photographs of Muruwari people, Culgoa River 1896.

Photographed by Gilsoe Kanter (1 of 3).

Mitchell Library PXB 1777, State Library of NSW

Early Experiments - Steam Power and Electricity

Jimmie’s investigation of steam power begins with the aforementioned sauce bottle experiment at Mundiwa. He built on this by adding lumps of carbide to bottled water and building his first generator that exploded not long after completion. These two experiments are linked and revolve around the principle of harnessing energy – in this case, steam.

The same principle underpins his early experiments in electricity generation. Jimmie describes rolling stones and boulders from a mountaintop near Tottenham at night “just to see the sparks fly.” Equally vivid are his descriptions of the electrical sparks “accidentally” produced by the belt of the chaff-cutting apparatus at Milroy.

This encounter led Jimmie to develop his first machine to generate electricity. As with the foray into steam power, these electrical experiments were not without personal risk. He and Billy rigged up a small pulley with a bicycle frame and wheels, and a belt made from horse reins, to generate electrical sparks. Jimmie recalls how he and Billy often got “a bit of a shock”. In an image that invokes the travelling shows of the period, Jimmie recalls inviting residents and visitors to Milroy to “come and see my electricity”.

It’s easy to forget Jimmie was a young boy, not yet ten years old, when he conducted most experiments recounted in Days Night and Day. In a further iteration of the experiment described above, Jimmie used two leather-edged discs to generate even more sparks. Jimmie recalls “we (he and Billy) had great games with this at night time” – reflecting how these experiments were, to some extent, a form of high-level play. But Jimmie also always looked for signs of experimental success – sparks, explosions or the “pretty little marks” of his sound recording devices.

Jimmie’s mother was unimpressed at her son consistently putting himself in harm’s way, and he received regular beatings – a fairly orthodox parental response to such behaviour at that time.

Maggie herself was under pressure, tied both to domestic servitude and the responsibility of raising two young boys. Jimmie’s grandson, Roy Barker, says Maggie “would’ve been trying to teach the lessons of what’s right and what’s wrong and trying to survive out there with the boys.”

Pretty Little Lines

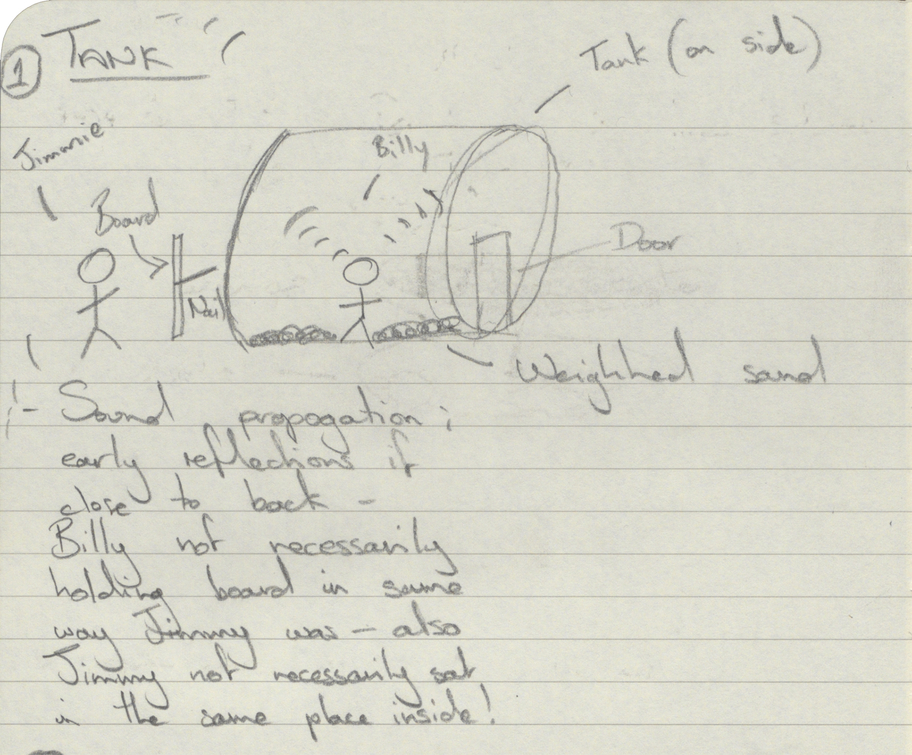

An old disused water tank lying on its side was a playhouse for Jimmie and Billy in their early days at Milroy station. Jimmie explains how an experience with song and vibration in this tank with his brother Billy set off a line of experiments that would culminate in Jimmie inventing, independent of any exterior knowledge, a form of sound recording using the same principle as wax cylinder technology.

This was arguably the most significant of Jimmie Barker’s innovations, and a sense of play is clearly at work in the epiphany that gives rise to it.

Jimmie notices that his brother’s singing excites the iron base of the tank (now positioned vertically) into vibration. He also notices the displacement of particles in reaction to this excitation. In the experiments that follow, Jimmie explores the link between vibration, displacement and inscription and sets about, in the words of Professor Samantha Bennett, “writing sound.”

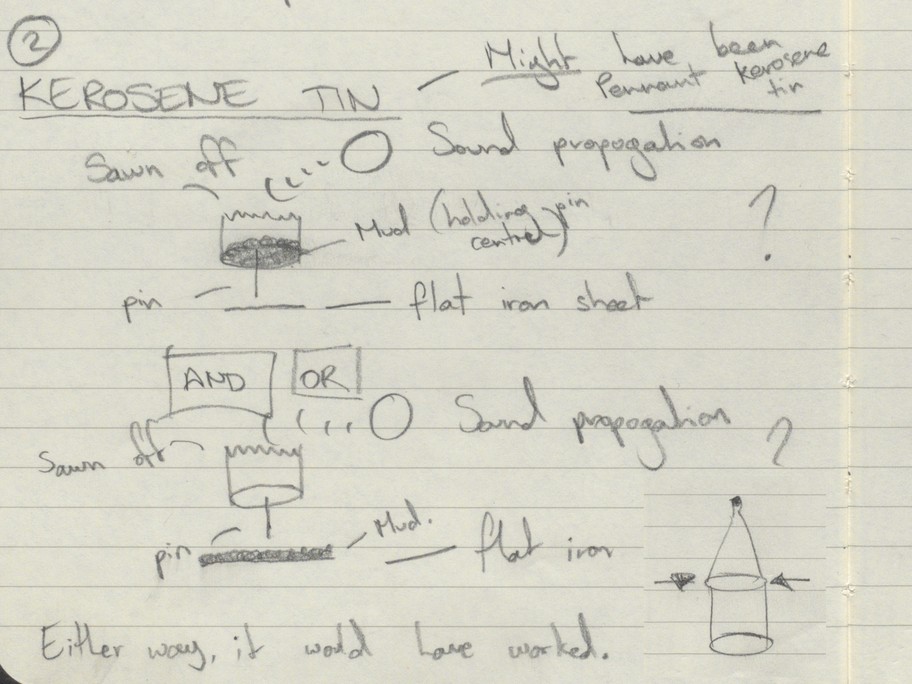

A second experiment involves a scaled-down version of the water tank: a kerosene tin. In this smaller resonating chamber, mud is introduced as the medium for inscription, fulfilling a similar function to the wax paper used in in Edison and Victor recorders of that era.

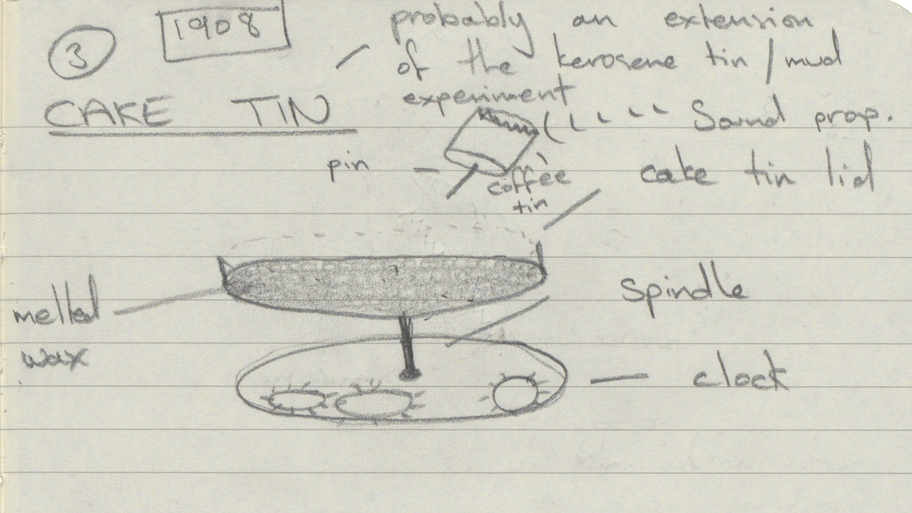

In the next phase of experimentation, Jimmie adds a spindle from an old clock and thus begins to mechanise his design. A cake tin lid is then added to the spindle and filled with wax by melting down his mother’s candles. In this third iteration, a coffee tin replaces the kerosene tin and the “pretty marks” are registered in wax rather than mud. As Samantha Bennett describes it, Jimmie Barker “wants to see if he can see sound and he wants to see if he can record it somehow … and capture it”.

In the fourth experiment, Jimmie introduces weights and string to the cake tin lid to stabilise it and successfully record sound.

Jimmie’s machine differs from the Edison and Victor recorders in that the recording medium is a disc or diaphragm rather than a cylinder. But both designs operate on the same principle. Samantha Bennett identifies this divergence as confirmation that Jimmie hadn’t seen these recorders and was operating independently. Why produce a design like this when it would have been far easier to try replicating a cylindrical design using a branch or a post?

All other available evidence confirms Jimmie’s claim to have been operating independently. Roy Barker noted recently “you can’t make this stuff up? You had to have done it.” These experiments to produce a means of recording sound fit the pattern of his other experiments (steam, electricity, munitions etc.), which nearly all seek to harness energy in some way. Jimmie explores an idea from first principles, often in response to an observation or encounter with natural phenomena.

Excerpt from Pretty Little Lines podcast

Transcript

Jimmie Barker: But it was in 1909. Billy and I used to play in an old tank, abandoned, it was lying on it’s side … and ah … it had quite a lot of sand in it and sand had blown all around it and it … the sand held it there. So ah … being an old tank and everything else, bottom wasn’t badly done but I cut one end out of it out and made a door with a tomahawk and put a bit of a fire in there to get rid of all the spiders and Bill and I used to play in it. In there singing little choruses we knew - we didn’t know many. And ah …. It was one afternoon I left Billy inside and I walked to the back of it … , sat there and I happened to put my hand up and um my finger nails must’ve been fairly long and the fingernails touched the tin … or the bottom of the tank really … and uh … while Billy was in there singin’ out and the vibrations came right through and I tried it again. So I didn’t say anything to Billy, I went and got a piece of board, drove a nail in it. I came back … And I told Billy “You sing out in there. Sing what you like.” He said “What for?” I said “Never mind keep on … singing.”

So while he was singing and making a noise inside I went to the back of the tank again and I held the nail up against the iron. And it was pretty um … well um … sort of corroded to do with the ah … weather. And while he was singing out, I held a nail up to the tin and the nail fairly jumped about! And it made pretty little marks I thought …. and ah …. then I got Billy I said “You hold this here and I’ll go inside and sing out.”

“Aw” he said “what for … you’re mad!” or something like that.

Anyway he held the thing up. I came out … and “what did you think of it?” or something like that. He said “aw …. nothin’ …. nothin’. I can’t hear anything in it.” Anyway that night I got to worrying about this.

Excerpt from Pretty Little Lines podcast

Transcript

Samantha Bennett: “…. make a smaller version of that.”

Jimmie Barker: So it was the next day. I couldn’t use the tank. It was too big. So, I got a kerosene tin … and ah … I could solder. I got a pin and I put it into the centre of the kerosene tin, in the bottom … and ah … put a sheet of iron, flat iron. Mixed up some mud. Made it pretty thick, not very thick, pretty watery. And spread it out over the tin and it dried quickly. Anyway, I got singing out inside the tin with a pin resting on the flat iron and sort of drag it along a little and it gave out these um … vibrations and left little pretty marks and I call them pretty marks. But then it was too awkward to hold in the tin and everything else. I didn’t know how to get about it.

So one day, up at the wash house, at the big house as they all called it. … And I knew this old clock, it was a very big clock … and ah … been left in the old wash house there and it was all smoky and everything else. I saw it quite often before and I asked the lady could I have it. She came across and had a look and she said “What are you going to do with it?” and I said “get it going.” “Aw” she said “grubby old thing” she said “take it away.”

Well, my heart nearly jumped up out of me. I was that happy about it. I had an idea. I had a key and I wound it up. Just putting the hand around – the great big hand … And ah … it made uh … it chimed. Of course, I couldn’t tell the time. And this went on for a day or so and one day I thought of this business about the tank … and ah … Billy and I were at our place and Mother was away …

Roy Barker: “Mmm ok”

Jimmie Barker: I pulled it to pieces. Well I didn’t pull it to pieces but I pulled some of the works out of it, to make it go faster. When Mother came back of course Billy told on me. That I broke the clock. Anyway, Mother got on the nasty side to me, gave me a few hits and “What did you do that for? Ruin the clock. Pull it to pieces.” But I said, “I wanted to make something else out of it.” But she didn’t believe me.”

Excerpt from Pretty Little Lines podcast

Transcript

Jimmie Barker: I kept dreaming about these pretty marks. So, one day I took the old clock, and I took parts of it out to make it go faster … and I …. rigged up a turn out on it ….

Roy Barker: “… rigged a turn out on it.”

Jimmie Barker: … with some parts that I had layin’ about there, some long string weights. And I um … got a cake tin lid … and uh … I fitted that on the top of a spindle, centre of the clock. And ah … I got a coffee tin and soldered a pin in the centre … and uh … I couldn’t get anything to … put in the um …cake tin lid … so that I could run the needle over. Yes I couldn’t get anything soft so that I could run over it with my needle. Sat about there thinking for a while and I thought of mother’s candles. So, I went and got them and I melted them up and I took the cake tin lid off the old clock and I filled it up with melted candles. Lift it out and got the smooth side … shoved it onto the old clock … and uh … I held the coffee tin and the needle on the uh … wax … And I was singin’ out there. I was makin’ pretty marks all right but hey was all over the place. Couldn’t hold it steady or anything like that. This was all right … I didn’t do any more really but just made all these pretty marks on the candle …..

Excerpt from Pretty Little Lines podcast

Transcript

Jimmie Barker: So then I worked on a better idea. I had these weights on both sides of the cake tin lid and …. and fitted the uh …. coffee tin and needle over the flat disc … and ah ….diaphragm really. It was attached to the string and I pulled it across as I sang out in it. Oh this was much better it got it’s own sideways … or side wise movement. We made quite a lot of pretty marks that way and uh …. We had this for quite a while. I was trying everything in place of the candles …. but they all came out as just pretty little things. Here and there you know in a straight line … round and round. But uh … I never realised then, although we actually recorded sound but we never reproduced the sound ….

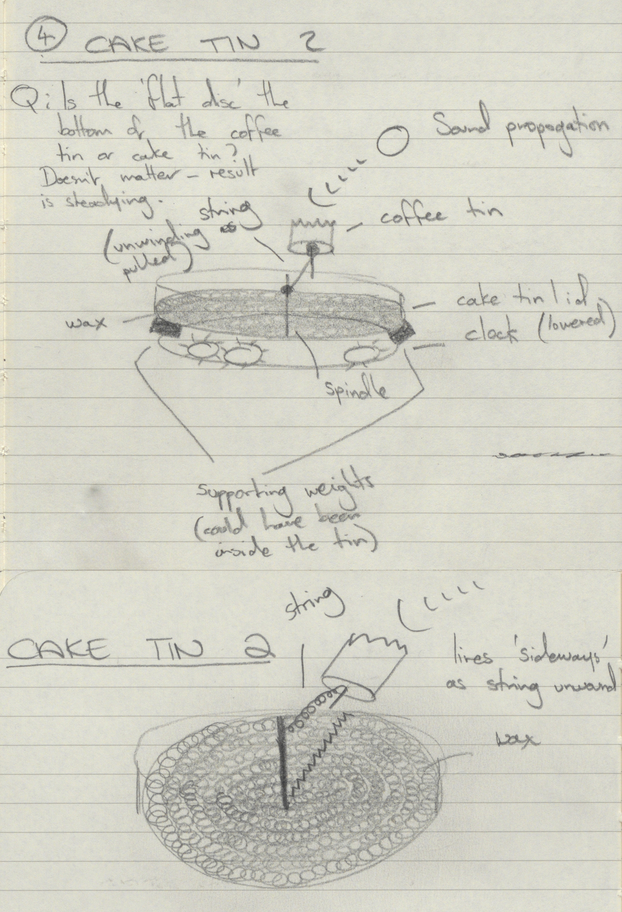

The machine that talks

Phonograph - Brewarrina Aboriginal Mission,1928

Pictured - Lily Hill, Jessie Kennedy and Leslie Smith Photo courtesy of New South Wales State Archives

The photo originates from the Aborigines Welfare Board and the photographer is unknown.

Phonograph - Brewarrina Aboriginal Mission,1928

Pictured - Lily Hill, Jessie Kennedy and Leslie Smith Photo courtesy of New South Wales State Archives

The photo originates from the Aborigines Welfare Board and the photographer is unknown.

Further proof can be found in Jimmie Barker’s descriptions of his first encounters with “the machine that talks” – commercial players/recorders.

In 1910 at Brigalow Bore, Jimmie is taken to see an “old cylinder type phonograph”. The second encounter takes place in the dining room of the homestead at Milroy where Jimmie viewed the newly arrived gramophone complete with the iconic His Master’s Voice porcelain dog. On this occasion Jimmie is able to inspect the machine closely, and sees in it the realisation of his own work.

Jimmie recalls inspecting the record: “I could see all these pretty marks … then I realised Billy and I, without ever seeing a machine like that … we actually made one of those recordings. But of course I didn’t know then that this was a machine patented 30 years earlier.”

Jimmie’s machine had, by this time, been broken down and repurposed to make mechanical toys. To come face-to-face with “the machine that talks” at this point must have felt like the fulfilment of a prophecy.

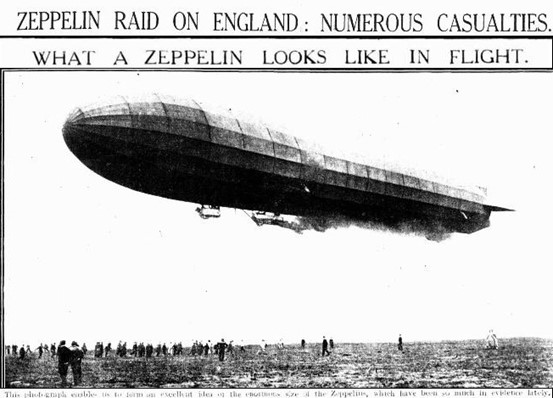

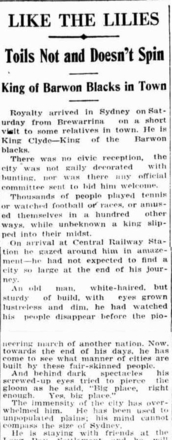

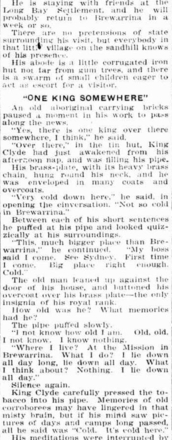

Zeppelin Raid on England: Numerous Casualties

In the next discussion on the same recording, Jimmie Barker tells another story of technological prophecy. On a hot day late in 1909, Jimmie was gathering pine gum (rosin) from beneath the trees. He describes resting in the heat under a beautiful tree and drifting off to sleep.

He recalls dreaming of being in a green field in a “different land.” The field was strewn with the smouldering ruins of unfamiliar machinery and a “cigar shaped” flying machine with two propellers approached from a great distance. The description, right down to the undercarriage in which two men were standing, is unmistakably a zeppelin-like aircraft.

Jimmie recalls discussing the dream with his mother Maggie who, as always, was concerned for his safety. She warned him about being abducted by spirits in remote places.

Jimmie set about building a miniature model of the aircraft from his dream, complete with propellers, and getting it to fly in a circle “on its own.” He and Billy rigged up an apparatus to propel the craft along an aerial wire attached to a fence. It was an enduring source of fun, particularly for Billy. They buried it there at Milroy just prior to leaving for Brewarrina Mission in 1912.

Jimmie encounters the image from his “queer dream” seven years later, in an edition of the Sydney Mail. Under the headline “Zeppelin Raid on England: Numerous Casualties” a photograph of a zeppelin over an airfield accompanies a report of a German air raid on the north of England.

Maybe all Jimmie Barker’s childhood inventions and innovations were technological prophecies of a sort – either after or before the fact. As Jimmie states, “In my early days when I was very small I could see things that were coming. I had different views to the others.”

He carried this prophetic ability into adulthood. In a 1972 recording, Jimmie reflects on the technological developments in power generation in the 50 years prior. Jimmie clearly envisages a big transition in the way that we generate and deliver power. Whilst he isn’t specific about the technology, his prediction of what he calls “perpetual power” could be taken to describe the global renewable energy transition currently underway.

Martin Thomas’s ABC Radio feature This is Jimmie Barker draws attention to Jimmie’s foretelling (in 1972) of a role for computers in relation to his language work.

“I have often thought of writing up a dictionary of the dialect but haven’t done. So today we’ll just have to take the words at random and perhaps leave the rest for the computers.”

Guwiyn Guwi Mysterious Lights

How do we attempt to track the evolution in Jimmie Barker’s fascination with light and electricity? Maybe it begins with the Guwiyn guwi or “mysterious lights”. Jimmie describes in detail his encounters with these “spirit lights,” a phenomenon common to many traditional Aboriginal cultures. These luminescent, otherworldly lights appeared to Jimmie variously in a dry lagoon, rising up out of rabbit burrows and on a lonely track during a puncture repair on a postal run from Goodooga to Weilmoringle. On one occasion, armed with a shotgun and a 32-calibre rifle, Jimmie considered opening fire on the light. In all cases the lights maintained a more-or-less constant distance from him, eluding his approaches. Jimmie describes them as orb-like, about as big as a football and notes they didn’t cast shadows.

Jimmie Barker’s account of the Guwiyn guwi, like that of the Guranggu is phenomenological. In these and other discussions of the spirit realm, as it was manifest in Muruwari traditional culture, Jimmie is measured, forensic and analytical. Jimmie’s grandson Roy Barker explains that such phenomena would have existed in the surface of everyday life for the Muruwari people. Perhaps it’s for this reason that Jimmie’s childhood accounts for such a large proportion of his life story, as reflected in Days Night and Day and The Two Worlds of Jimmie Barker. The direct line with the generation of “pre-contact” Muruwari provided a window into this lived reality.

The Guwiyn guwi were well known in Muruwari culture. Jimmie likely learnt of them from the “old people,” years before his first sighting in 1910 from the floor of a horse-drawn buggy where he was stretched out at the feet of the “three men” he was travelling with by night.

Halley's Comet

Perhaps Jimmie’s observation of Halley’s comet, also in 1910, fired his scientific imagination. As we know, this event stopped the world in a similar way to the moon landing of 1969. Jimmie was at Milroy and viewed it from an open-air camp. He recalls being woken by the “old lady” – his mother Maggie. We know the experience overwhelmed Jimmie. At one point he recalls feeling the world was coming to an end. It triggered a lifelong interest in stargazing, typically from the dual perspectives of Aboriginal astronomy and the western empirical viewpoint. Jimmie and Billy tried to replicate the comet tail using sticks of phosphorous pilfered from the “poison shed” at Milroy.

"I though the world was coming to an end"

Transcript

It was one night, a warm night and I don’t know what month it was. Anyway I was laying out in the open, beds out … fast asleep. The old lady she umm … woke me and … woke me up and she said umm … in the dialect, she said “look at this big storm.” Awe and the sky turned red and it was like there was big … ah … streamers coming up, stars in between them you know like they were moving between the streamers. And they’d die out … big flashes of light … go right across the sky … turn green … pretty well right overhead … and very low in the south. When we watched that thing you know and I’m shivering … oh I thought the world was coming to an end.

Brewarrina Mission Station

The year 1912 marked a significant turning point in Jimmie Barker’s young life. A new Aborigines Protection Board Act had made school attendance mandatory for Aboriginal children. Jimmie records that it might have been possible for him and Billy to be schooled at Milroy Station as a governess was employed there. But he recalls his mother Maggie was “advised,” or perhaps pressured, not to take up this option. As a result, she moved with Jimmie and Billy the 40 miles across to Brewarrina Mission Station. They arrived on New Year’s Day in 1912.

Brewarrina Mission Station had come to be both a selection yard for indentured Aboriginal labour and a halfway house for people syphoned through the domestic and farming training homes, such as Cootamundra home for girls and Kinchela home for boys. The mission was a key link in the chain of Aboriginal labour that fired the rural economy of Northwest NSW. Jimmie experienced this firsthand when, aged 15, he was ‘apprenticed’ to a station in Tottenham with the promise of an education in mechanical engineering. But this turned out to be purely a labouring assignment. The sense of betrayal Jimmie felt is heartbreakingly told in The Two Worlds of Jimmie Barker.

Soon after this Tottenham assignment concluded Jimmie accepted a job as handyman at Brewarrina Mission Station in 1920. A large part of his job involved transporting young people from the mission to their work assignments. Between this, other transport work and his responsibilities developing and maintaining the Mission infrastructure, Jimmie somehow found time to pursue his interest in sound technologies.

A remaining hut at the Old Mission, Brewarrina, NSW, 1985.

Photograph by Sandy Edwards

AIATSIS Collection BREWARRINA.001.BW-B00025_34A.

A remaining hut at the Old Mission, Brewarrina, NSW, 1985.

Photograph by Sandy Edwards

AIATSIS Collection BREWARRINA.001.BW-B00025_34A.

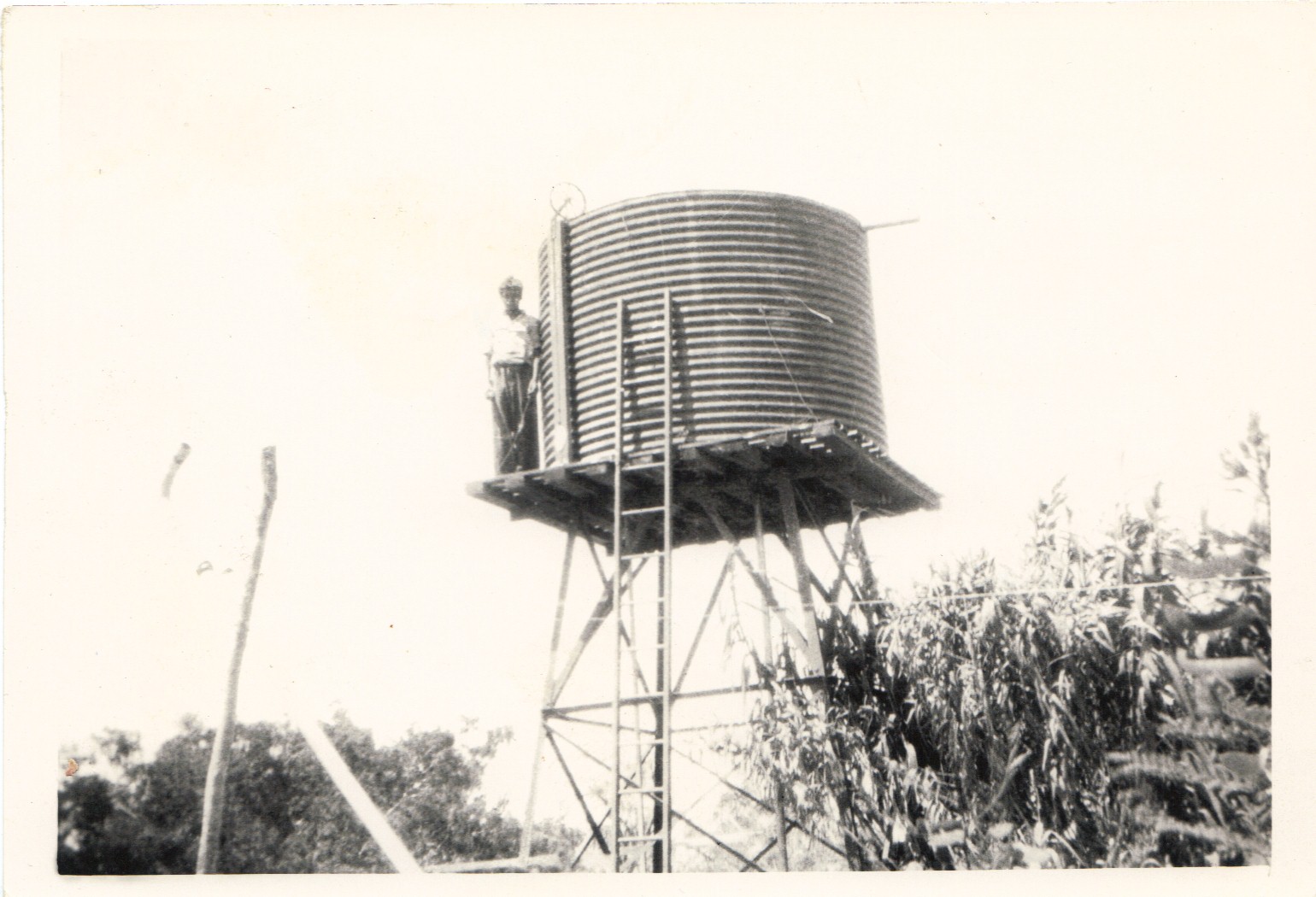

The Water Tank

Jimmie Barker built this water tank and stand from raw materials and the pumping station in the background. Prior to this water had to be hauled directly from the river for use by Brewarrina Mission Station residents for drinking, ablutions and the Mission gardens. Initially there was one central tap as a point of access. Jimmie expanded the infrastructure to provide a water outlet to individual residences and the effect on people’s lives was truly transformative.

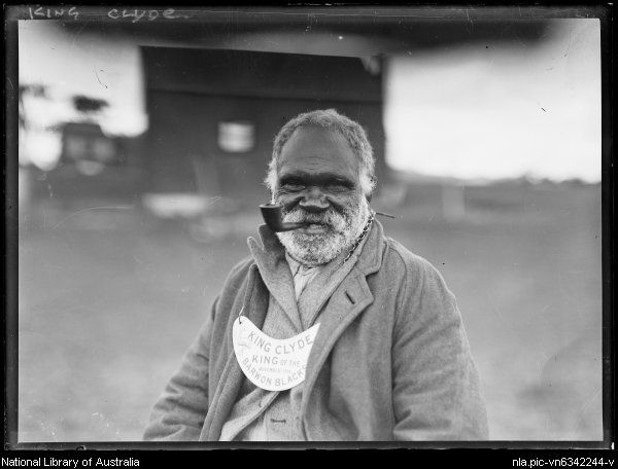

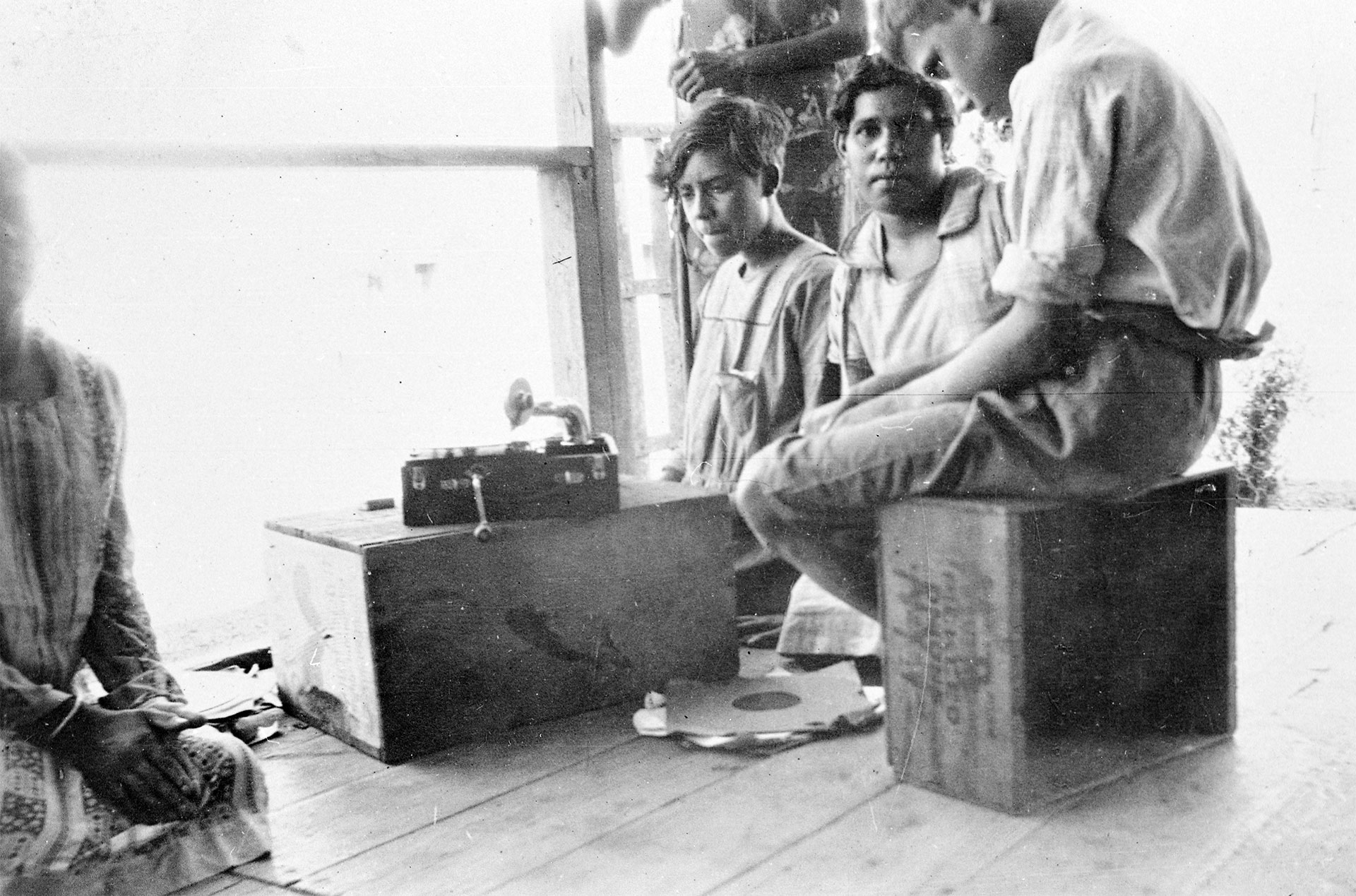

Jimmie describes how, in his little house on the mission, a room was given over to the entertainment and education of children. Jimmie had a projector for “a bit of a picture show,” a blackboard for literacy and numeracy and a large school clock for time-telling. Jimmie also had a phonograph which, in keeping with the Edison and Victor machines of the day, could record sound directly onto wax cylinders. In this room, Jimmie began recording residents of the Mission singing traditional songs and language. Among them were a generation of Muruwari and Ngemba people, then aged in their 80’s, who would have known pre-settlement life in the area. Clyde Marshall – King Clyde of the Barwon Blacks – was among them. He was a Muruwari man who had been given King Plate status.

Thus, Jimmie Barker was the first Indigenous Australian to independently use sound recording to preserve and document Aboriginal culture. It wasn’t until almost 20 years later, in 1938, that Norman Tindale arrived at Brewarrina Mission Station and recorded Wanjiwalku man George Dutton, as part of his ethnographic mission.

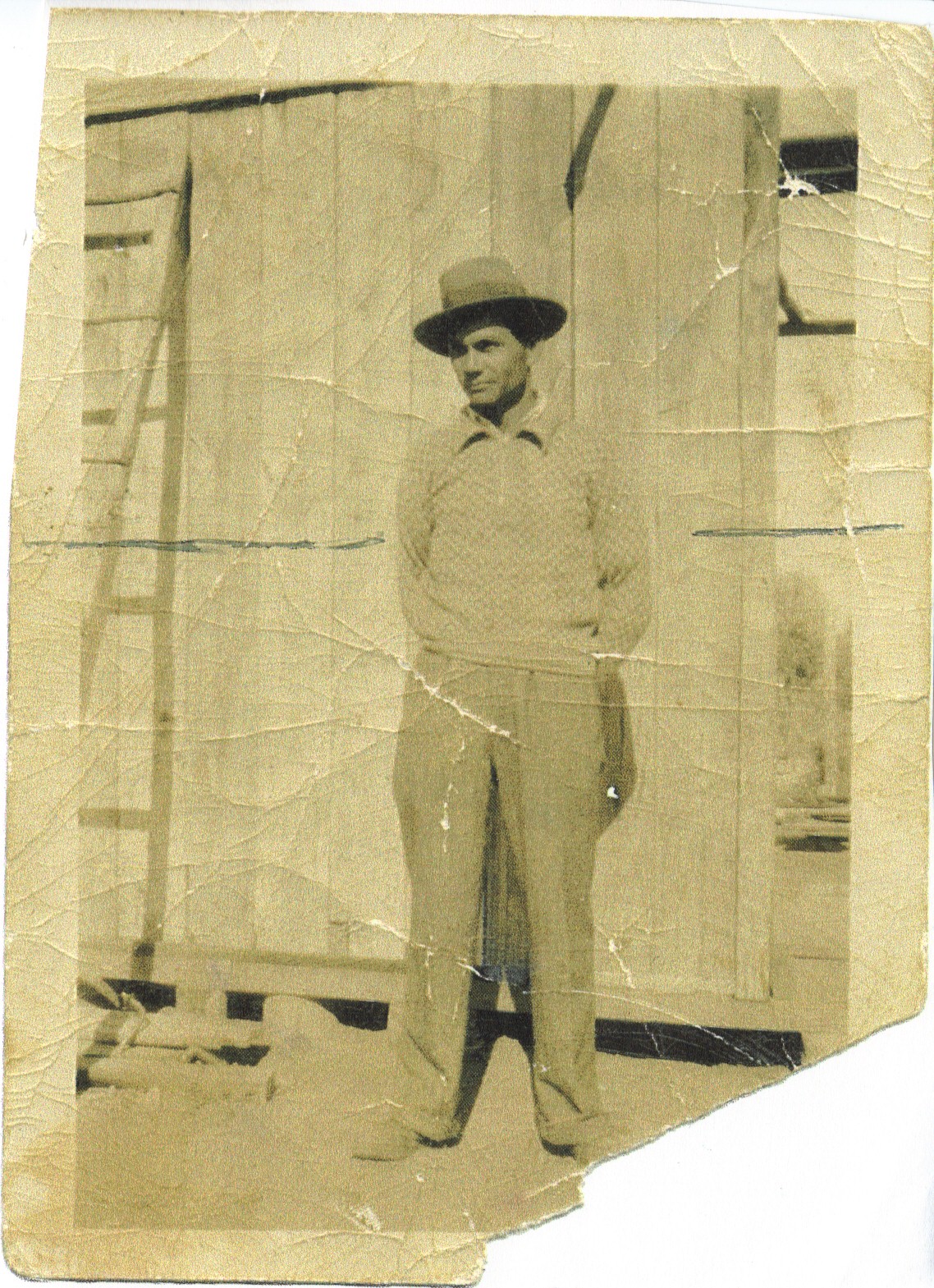

Jimmie Barker

In the 50 years he was attached to the mission, Jimmie Barker had many chances to “get away.” He had a prodigious engineering talent and he was drawn to a life at sea or on the railways. But in every instance, Jimmie chose family and community over personal fulfillment. Had Jimmie’s life followed a different path he may not have left us this treasure of Indigenous history – an extraordinary legacy of over 100 hours of recorded sound, encompassing Muruwari language and cultural heritage.