‘We’ve been doing it [fishing] in this country thousands of years more than white men put together have been doing it; we know how fish react, we know how they travel, we know where they travel, we know what time of year they travel. Our parents taught us, we were brought up living off the sea.’ — Tom Butler, Murramarang Elder and retired commercial fisherman, 2016

Fishing forms part of the deep cultural and spiritual connection many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have with their oceans or inland waterways that form part of their Country.

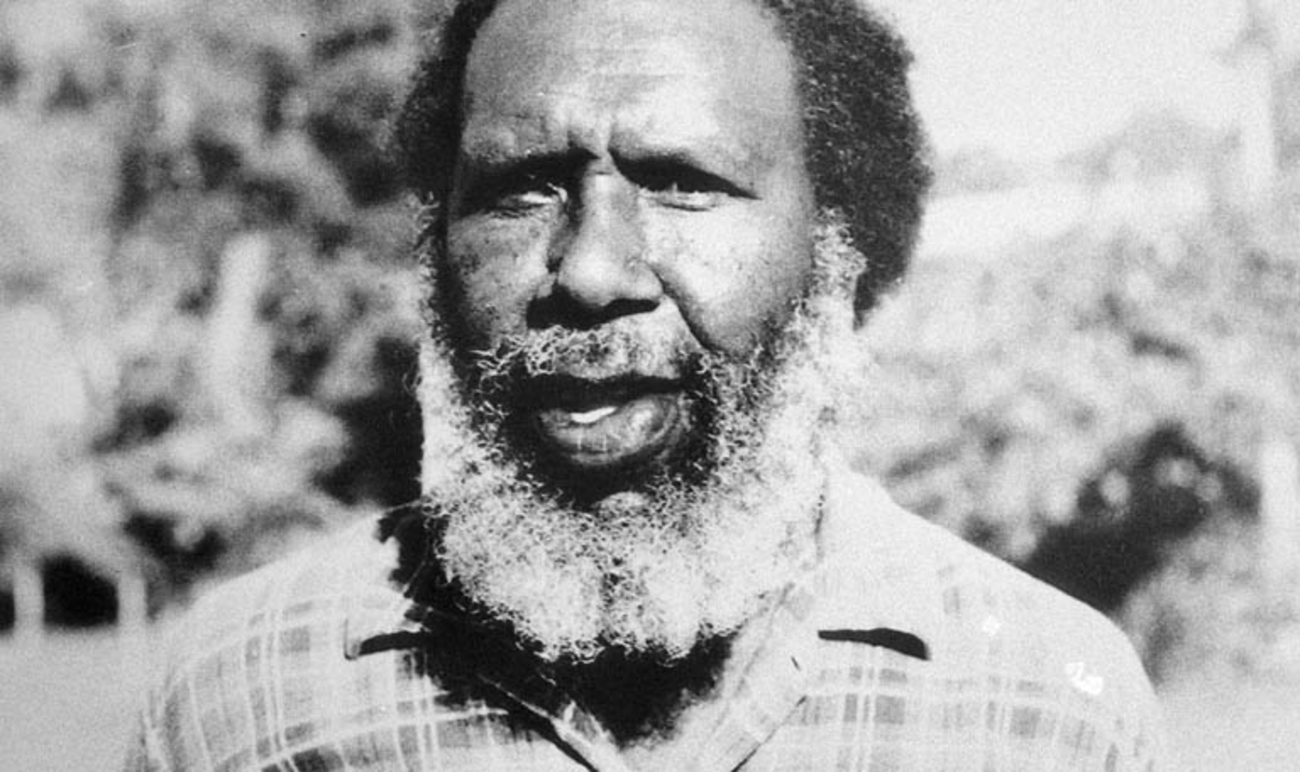

Fishing activities of Aboriginal people and settlers near Ulladulla, New South Wales, approximately 1885, Mickey of Ulladulla. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, nla.obj-135516869.

Fishing activities of Aboriginal people and settlers near Ulladulla, New South Wales, approximately 1885, Mickey of Ulladulla. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia, nla.obj-135516869.

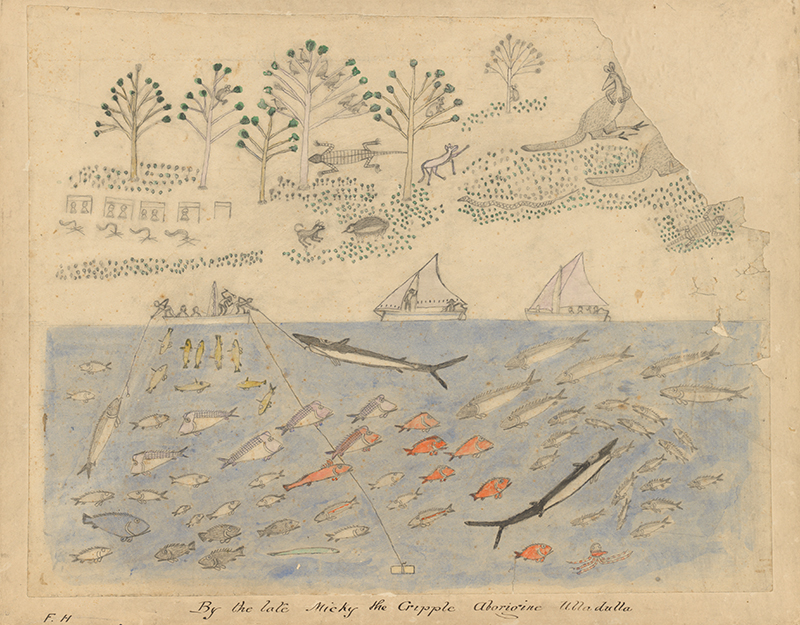

Sawfish dance, 410, Thursday Island (Waiben), Torres Strait, c. 1893. Artist Trevor Haddon. Courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, P.1124.ACH1. Drawings based on photographs taken by Trevor’s brother AC (Alfred Cort) Haddon during his Torres Strait Island Expedition.

Top image shows two Muralug men dressed for the Waiitutukap (Dance of the Sawfish), facing each other.

Bottom image shows two masks collected by AC Haddon after the ceremony, now held in the British Museum. AIATSIS Collection HADDON.001.BW-N02129_36.

Sawfish dance, 410, Thursday Island (Waiben), Torres Strait, c. 1893. Artist Trevor Haddon. Courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, P.1124.ACH1. Drawings based on photographs taken by Trevor’s brother AC (Alfred Cort) Haddon during his Torres Strait Island Expedition.

Top image shows two Muralug men dressed for the Waiitutukap (Dance of the Sawfish), facing each other.

Bottom image shows two masks collected by AC Haddon after the ceremony, now held in the British Museum. AIATSIS Collection HADDON.001.BW-N02129_36.

Sawfish dance, 440, Thursday Island (Waiben), Torres Strait, November 1888. Photograph by AC (Alfred Cort) Haddon. Courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, P.1154.ACH1. Taken by A.C. Haddon on his Torres Strait Island Expedition.

Group of four Muralug men dressed for the Waiitutukap (Dance of the Sawfish), wearing large tin masks and zazi (grass skirts). The front of the mask takes the form of a crocodile’s head with an open mouth; the back has a wig of hair. On top of the mask are two long poles, the horizontal one shaped like a sawfish, with lines of feathers joining the two.

To the right two other men sit playing warup (hour-glass shaped drums).

Sawfish dance, 440, Thursday Island (Waiben), Torres Strait, November 1888. Photograph by AC (Alfred Cort) Haddon. Courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, P.1154.ACH1. Taken by A.C. Haddon on his Torres Strait Island Expedition.

Group of four Muralug men dressed for the Waiitutukap (Dance of the Sawfish), wearing large tin masks and zazi (grass skirts). The front of the mask takes the form of a crocodile’s head with an open mouth; the back has a wig of hair. On top of the mask are two long poles, the horizontal one shaped like a sawfish, with lines of feathers joining the two.

To the right two other men sit playing warup (hour-glass shaped drums).

Connected to country and community

‘This is who our family is. We are bound to the sea and we have fished together traditionally forever.’ — John Brierley, Yuin Walbunga self-employed fisherman, 2011

For saltwater communities, the sea is integral to many people’s concepts of country and identity.

In northeast Arnhem Land, the Yolŋu peoples consider the land and the sea to be inseparably linked, both physically and culturally. Under Yolŋu law, traditional owners have an equal responsibility to look after the resources and environment of both their land and sea estates.

For thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have used fishing to build a livelihood for themselves, their families and their communities. A catch of fresh fish provides a community with immediate subsistence and future trade and sale options, as well as employment. In this way, fishing is crucial for the continued success of coastal Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community economies.

Frozen crabs in the freezer ready for export as part of the crabbing industry at Milingimbi, Milingimbi Island, NT, c. 1965. Courtesy of the Fidock Collection, 118.

Frozen crabs in the freezer ready for export as part of the crabbing industry at Milingimbi, Milingimbi Island, NT, c. 1965. Courtesy of the Fidock Collection, 118.

Jeffery Dhupuditj Garrawitja (Birrkili) packing frozen mud crabs at Ŋamuyani for transport by air to markets in the south, Milingimbi Island, NT, c. 1965. Courtesy of the Fidock Collection, 1062.

Jeffery Dhupuditj Garrawitja (Birrkili) packing frozen mud crabs at Ŋamuyani for transport by air to markets in the south, Milingimbi Island, NT, c. 1965. Courtesy of the Fidock Collection, 1062.

In the Torres Strait, marine management arrangements provide Torres Strait Islanders with priority access to subsistence marine resources. Since 1985, new commercial licenses for fisheries such as trochus, pearl shell and crayfish have only been issued to traditional inhabitants.

For Wayne Carberry, a Walbunga man, fishing on Country gives him his identity, sense of belonging to Country and connection with both ancestors and family today. These relationships are strengthened by cultural fishing rights and access to traditional waters.

The men on Mornington Island traded the fish for tobacco. The fish were also used for dormitory children's meals, Mornington Island, Qld.1946. AIATSIS Collection BELCHER.D01.DF-D00018770.

The men on Mornington Island traded the fish for tobacco. The fish were also used for dormitory children's meals, Mornington Island, Qld.1946. AIATSIS Collection BELCHER.D01.DF-D00018770.

Fishing technologies and knowledge

‘I think Aboriginal people have the common knowledge to know where they can fish and can't fish, it's in their blood, it's in their culture, it's been passed down from generations.’ — Sue Stewart, Yuin woman, 2016

A lot of coastal Indigenous fishing is done on the beach or in shallow pools. Shellfish such as cockles and crabs can be dug up from under the sand. Rock pools work as natural tidal fish traps to ensure that when the tide goes out, fish are caught in the pools, ready to be speared.

On a larger scale, built stone weirs designed to trap fish in shallow lagoons with the falling tide can be found in most coastal areas of Australia. The construction of these traps over hundreds of years demonstrates the technological capability of Aboriginal people in these areas.

In areas along river and creek systems, such as Maningrida in the Northern Territory, people developed basket fish traps and hand-held nets made of woven fibres. Basket traps could be placed into creeks for use during king tides, while hand-held nets could be used at any time.

‘Aboriginal fisheries’, fish trap on the Barwon River, Brewarrina, NSW, ca. 1890. Photograph by Henry King. AIATSIS Collection KERRY_KING.001.BW-N03159_01.

‘Aboriginal fisheries’, fish trap on the Barwon River, Brewarrina, NSW, ca. 1890. Photograph by Henry King. AIATSIS Collection KERRY_KING.001.BW-N03159_01.

Fish trap – the trap will be positioned in the gate when the tide turns and water begins to flow out, Bulgai Plains, between Liverpool River and Tomkinson River, Arnhem Land, NT, 1978. Courtesy of Peter Cooke. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074171.

Fish trap – the trap will be positioned in the gate when the tide turns and water begins to flow out, Bulgai Plains, between Liverpool River and Tomkinson River, Arnhem Land, NT, 1978. Courtesy of Peter Cooke. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074171.

On Murruŋga Island in the Crocodile Islands, fish traps made of twined pandanus palm leaf are still in use today. Though, for the most part, modern nylon nets have become the marine technology of choice for most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The same weaving techniques can be used for both natural fibres and synthetic polymers to make and mend nets.

Frank Malgurda weaving a sedge grass 'drag net', Maningrida, Arnhem Land, NT, 1980. Courtesy of Peter Cooke. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074162

Frank Malgurda weaving a sedge grass 'drag net', Maningrida, Arnhem Land, NT, 1980. Courtesy of Peter Cooke. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074162

Another significant marine technology development is the use of rafts, canoes and boats along river systems and on open waters. Historically, dugout and bark canoes were used as transportation devices and as flotation aids while spear fishing. Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples primarily take dinghies out to fish, and use nets, spears and fishing lines with metal hooks rather than kangaroo bones.

Diving is also a traditional practice for collecting sea snails such as abalone, particularly on the South Coast of New South Wales.

(Left to right) Brad and Newton Carriage diving for mutton fish (abalone), Batemans Bay, NSW, March 1989. Photograph by Ricky Maynard. AIATSIS Collection SOUTHCOASTNSW.001.BW-B01033_09.

(Left to right) Brad and Newton Carriage diving for mutton fish (abalone), Batemans Bay, NSW, March 1989. Photograph by Ricky Maynard. AIATSIS Collection SOUTHCOASTNSW.001.BW-B01033_09.

Over the generations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living near the sea have amassed a great deal of knowledge around the best times and places to fish:

‘Tides will tell us [when to go out fishing]… the weather will tell us. Those balanda [white people], they’ve got fish radar but we don’t use that one. We know the places to get what we want, it’s there. What we don’t want, we just leave it.’ — Jonathan Yalandhu, Yolŋu man of the Gupapuyŋu clan, 2017

Yolŋu people describe this as seasonal knowledge. They know which season it is from the natural signs around them: different flowers in bloom, changes to the colour of leaves, changes in tides and winds. The signs and seasons tell them which fish and maypal (shellfish) are big and fat, ready to be taken. Changes in the colour and smell of the sea brought by algal blooms tell them when there are yindi maypal (big shellfish).

Michael Gadjawala with a group of people working with a mud crab net in shallow salt flats on the east side of Cape Stewart, central Arnhem Land, NT, 1978-1979. Photographer unknown. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074182.

Michael Gadjawala with a group of people working with a mud crab net in shallow salt flats on the east side of Cape Stewart, central Arnhem Land, NT, 1978-1979. Photographer unknown. AIATSIS Collection COOKE.P01.CS-000074182.

Wayne Haseldine, a Kookatha/Mirning man, describes knowing which fish species to target on particular days as a ‘natural instinct’ made up of his ability to read the tide, winds and the moon. This is the knowledge he wishes to teach the next generation of his family.

With the advent of new technologies, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ means of engaging in fishing and marine resource management has changed a great deal. But the traditional knowledge of how, where and when to gather marine food resources such as fish and shellfish hasn’t changed.

Cultural continuity

As a continuous practice spanning thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fishing has been well documented in the archival record, particularly in material held in the AIATSIS Collection. People often think of archives as collections of sepia photographs, decaying films and dusty papers about a distant past. But archives are living things, constantly growing to reflect changes in society and the way people think.

- View a gallery of selected drawings and photographs from the collection which are significant for what they convey about how fishing has historically been practiced and perceived.

Take only what you need

In coastal Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, cultural rules about fishing are handed down orally through the generations:

‘Fishing is actually sacred to us; it’s really part of our culture. So if people want to go fishing and if they want to do it our way, then they’ll learn the sacredness. You never take more than you need, for a start.’ — Sue Haseldine, Kookatha/Mirning woman, 2017

This rule is widespread, and often accompanies two others: don’t take undersized or pregnant fish and don’t overfish. When fish are allowed to breed and grow, their populations both are sustainable and can sustain a community when taken at the right time.

In Aboriginal communities where cultural fishing practices have been handed down for thousands of years, people express frustration at not seeing commercial and recreational catch and release fishing boats following the same rules, showing respect to the marine environment and improving their efforts at fishing sustainability. When people in these communities see examples of bycatch and discarded dead fish, they see this as disrespectful of their culture and their Country.

Many Yolŋu peoples in the Crocodile Islands believe that there are fewer fish in their waters due to commercial fishing. In Ceduna, on the Far West Coast of South Australia, people worry about the impact on the local fish populations due to the thousands of recreational fishers who visit every year.

The Crocodile Islands Rangers (NT) manage and protect 80,000 hectares of land and 740,000 hectares of sea country, which includes 200 kilometres of coastline.

The Crocodile Islands Rangers (NT) manage and protect 80,000 hectares of land and 740,000 hectares of sea country, which includes 200 kilometres of coastline.

In Ceduna, the Aboriginal community would like to see the advent of a sea ranger program, where local Aboriginal people could enforce fisheries regulations in a culturally appropriate way. Sue Haseldine wants to start a cultural eco-tourism business which would teach people respect for the land and the sea. These programs would not only provide employment, they would provide new opportunities for Aboriginal people to explain to outsiders the sacredness of their connection to sea country and the importance of respecting the cultural rules of fishing.

Today, these long-held traditions have become increasingly challenged. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have been marginalised from both commercial and non-commercial fisheries, and are often denied access to their traditional waters. But across Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fishers are taking steps to ensure their voices – and values – are heard in fisheries management planning, negotiating catch allowances and controlled access to their waters and marine resources.

The right to fish

Laws on where and how people can fish differ across the country. When the states first began bringing in laws to manage fisheries in the early twentieth century, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were often exempted from having to get fishing licences because it was acknowledged that they needed to fish to feed their families.

As time went on and fisheries legislation was updated, many states removed special exemptions for Aboriginal people. In recent years most states have recognised Aboriginal rights to fish in some way. This recognition has come in a variety of different forms, including introducing customary fishing permits (Victoria), recognising Aboriginal customary fishing as its own sector with its own regulations (Western Australia), and mostly exempting Aboriginal people fishing on their traditional lands and waters from fisheries regulations (Northern Territory).

Native title has played an important role in securing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights to access and manage their traditional fisheries free from regulation.

Land rights and the sea

Alongside native title, many state and territory governments have statutory land rights systems where governments can hand back Crown Land to Aboriginal communities. These are different from native title in that communities are usually given the land as freehold – meaning that they legally own and control the land.

The Northern Territory’s land rights system is the oldest, established by the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth). About fifty per cent of land in the Northern Territory has been handed back to Aboriginal communities through the land rights process.

In addition to handing back land, the territory’s system lets traditional owners apply for what are called ‘sea closures’. Where a group owns coastal land, they can make an application to prevent outsiders from entering and fishing in seas within two kilometres of their land without their permission. Whether the closure is successful or not depends on the group proving that their traditional laws give them the right to exclude strangers from those waters.

So far there are only two sea closures: the Milingimbi, Crocodile Islands and Glyde River area, and the Howard Island and Castlereagh Bay area. These areas border each other, and both closures were prompted by concerns over non-Indigenous fishers taking too many fish and disturbing sacred sites.

Government policy concerning fisheries management often doesn’t take Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities into account. In non-Indigenous commercial and recreational fishing sectors, the value of a catch is quantifiable in both direct and indirect ways. It is easy to see the economic value of selling fish and seafood. Recreational fishing undertaken by the tourism industry also holds economic and cultural value.

The value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customary fishing is less clearly quantifiable. One example of this is the cultural value of spiritual relationships with, and access to, marine territories and sacred sites. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander values, particularly social and economic values, are often conspicuously absent in the development of fishing management strategies and policies.

Part of this is because many people incorrectly assume that customary fishing and commercial fishing can’t overlap, or that contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander commercial fishing somehow isn’t ‘traditional’. In fact, customary fishing has always had an economic element as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples fished to survive and to trade.

‘We were made out to be criminals, and we weren’t even criminals, it was who we were, it’s in us, it’s culture, our way of life; if we could make some money out of it we should’ve gotten that opportunity too. We had trade and barter before they came along, in traditional times they bartered. But they just expect that blackfellas, if you want to go fishing, go fishing in a canoe.’ Wally Stewart, Yuin native title claimant and cultural fishing advocate, 2016

Plenty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander commercial fishers use Indigenous cultural knowledge and practices they learnt from family and Elders in their work, and are proud of making a living on their country and using their culture and resources. For many communities the commercial fishing that happens today is a continuation of what their ancestors did prior to colonisation, with their fishing practices adapting over time to the changing cultural and economic environment.

For government and regulatory bodies to be able to take Indigenous customary fishing values into account when developing fisheries management policies, these values need to be clearly articulated and able to be interpreted.