In the 1980s, Pike’s innovative use of bold bright colours stood in contrast to the dominant forms of Aboriginal art of the time; the ochre toned bark and canvas paintings from Arnhem Land and Central Australia.

Pike was also a trailblazer in the promotion of his art internationally. His imagery licensed to Desert Designs, became a fashion sensation not only in Australia but also in Japan, America and Europe.

With his British born wife and collaborator, Pat Lowe, Pike co-authored and illustrated a number of publications including Yinti (1992), a fictionalised account of Pike’s life as child growing up in Great Sandy Desert. Pike’s family was one of the last groups to move out of the desert, settling at Cherrabun station in the Kimberley region in the mid-1950s. As a young man, Pike saw windmills, car tracks and other signs of European settlement for the very first time, on cattle station country. The collection includes drawings with recollections of this period.

Audio recording of Jimmy Pike

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this recording contains voices of deceased persons.

-

Transcript

Recording and transcription by Pat Lowe.

Because old people believe in Dreamtime story and law. How people can follow track. Follow track mean they can sing song without books — people got them in their mind. How them old people bin teach all the young people, long long time ago. From Grandpa and his father — the law. That’s what I’m talking about here now — all them story from every jila. Because every jila, from Dreamtime, jila, they still got water, today. Man can go up there and just clean the sand; water will come out, no problem. Only just cleanim out. Water will get up from ground. Cold water. That water from Dreamtime.

They called jila because he got rainbow snake under the water. Rainbow snake mean he was a man before [in the] Dreamtime. He bin moving round, same like a man. But he was a tall man, that water snake was a man, before. He was a tall man, and big, long hair, long whisker. That’s the way people used to clean the water, chuck all the mud in a line, right round. They used to talk to the spirit: We’ll just wait, next time, you will send rain, three days’ time, we wantim. Old people used to talk to the water snake. Because rainbow snake can listen to man, what they’re saying. People used to talk to spirit.

Mightbe three days time, cloud come out, and after, big rain. That the way they bin doing, long time ago. That’s the way we call Dreamtime, waterhole. Because they got song for rain, they can make big rain. They used to make big rain before. Not now. Because in some place very danger, very danger. Because water snake, he’s a powerful one, spirit. He can break the tree, washimout road, breakim houses. Sometime he’s danger, big strong wind, he can just spreadimout, trees and houses.

That’s the way we call strong wind karliwiji. Karliwiji mean, he’s like a cyclone, strong wind. Karliwiji from jila, powerful one, he can clean the houses, breakim all the trees, windmills, everything, clean the lot. That’s the jila country. Wind. People used to make big wind, or big lightning, rain, before. They go there, talk to spirit. Spirit mean rainbow snake. He listens to people, what they’re saying. They used to tell the snake — they give him time, what time, mightbe four days’ time, mightbe three days’ time, big rain. They used to tell the spirit which way, you want to go that place, they used to callim name, he go to that place.

That’s why people sometimes worrying about for dreamtime waterhole. Because he good. Man can go back and stay round there, the dreamtime waterhole. Because sometimes people thinking about Dreamtime waterhole, because he got snake, he’s friendly. To people. Friendly mean, because — for rain. Makim come rain. That’s how people bin believing, all them people before, long, long time ago. They used to sit down with the people, talk to them. When he get summertime, Ah, we’ll have to dig, dig the jila down, digim down, dig that jila down, so we can get plenty water. They used to tell the other people, everybody, Dig it down.

Sometimes, when they see big cloud coming up, they used to makim mangkaja. Mangkaja means bush house. They used to put four rails, sand, sand, spinifex, more spinifex top of it, double, make good house. Doesn’t matter how much big rain bin come, these people bin live there, under the mangkaja. Mangkaja mean house, bush house. That’s the way they bin doing, long time ago. My father used to makim mangkaja. He used to tell us, when you see cloud coming up, black and yellow, that’s a danger. And nother one, red cloud, that’s a danger. He can kill people. Danger mean plenty lightning, too much rain, and strong wind. That what they call yellow cloud, yellow and black cloud, and red cloud. That’s jila law. Where the jila bin put law. That’s the danger, he can kill people. That’s the way he make yellow cloud, and black and white cloud, and red and yellow. Red. You can see red, bottom part. Dark cloud and red. Maybe afternoon time. That’s a danger. That’s water snake. Angry. That’s when you see red cloud bottom and half, half up.

They used to tell us story: You gotta make strong houses. Or sometimes they used to go, get into cave, under rock. When people bin living all the time, in a cave. They used to tell us story: When you see big rain coming up, sometimes yellow and black clouds, that’s danger. You gotta go under the rock. He got a big cave in, big cave under the rock. People used to live in one of that kind of house before, big rain time. They used to show me that place. When rainy time, we used to live in a cave, when I was a little boy. My father used to live in a cave, and my mother, big rain time.

When rain finish we used to go out, outside, in the bush, go every waterhole, jiwari. Jiwari mean rockhole. Wirrkuja: wirrkuja mean rockhole, small rockhole. In a flat rock. They used to tell us, when everything bin dry, grass and food, they use to tell us, Ah, we better go back to jila. It’s getting dry, everything. That means barranga. Barranga means summertime. We used to get back, right back to jila, live round the jila, right through. Till rain, can’t seeim. And after rain, we used to go out again, round jiwari, wirrkuja. That mean, wirrkuja, jiwari, rockhole. Jumu — little waterhole. Not jila. We used to go out from jila now. In the bush. Long way round — hundred miles away.

We used to go right round, they used to take us round bush, getting plenty food, wild tomato, all different wild tomato, pura and kumpupaja. That’s the food for the hot weather, summer time. They used to get big mob, plenty. Pura and kumpupaja. Wild tomato. And lungkurn, that’s from wattle tree, for summertime food. And kuwarrr. And karlayin mean that same food: he got two name. That lungkurn, he got one name. And pingkarla, another food, from wattle tree. They used to get plenty. From lirrara — lirrara means, from ants, big ants eat and makim, plenty. And people come along and gettim from ants, pickim up. My mother used to pickim up, food from ants — they used to makim plenty.

That was summertime. And ngarlka. Ngarlka mean bush peanuts. My other used to get bush peanuts, plenty. And kurrungkampa. Kurrungkampa, that’s a food from after rain. They used to make big damper, like flour, and bush onion, they call salad, that bush onion. They used to get plenty food, bush onion, anything. That’s all the people bin living with that food. In the bush. Bush country, long time ago, long, long time ago. They used to get big mob. That’s what all the people bin living with, the food, all them wild food. That’s only the main thing is, they used to get plenty rain, because rain can make grow. Any grass. Rain is the main — they used to wish for rain. If plenty rain, plenty food. He makim come out from ground. That’s all the jila. They makim jila, they digim right down, and they talk to jila. They tellim, they used to tellim, we want plenty rain, so we can get plenty food, in the bush. Because water snake, spirit, he listen to people. They know what they’re talking about, what they want. He can listen to them. Because he’s a man. When he was a man, before, and he bin turn into snake, water snake. That’s the way we call jila, every jila, because he got law. He made the law, big law for jila. That’s why people worrying for jila: I want to go back to jila. Because he’s got story, from Dreamtime, Dreamtime means Jukurrarni and Ngarrangkarni. And jumangkarni. Jumangkarni, Ngarrangkarni and jukurrarni, that’s all the Dreamtime words.

They used to tell us that word, story. They used to tell us sometimes: When you see something, sundown, when the sun going down, maybe four o’clock or three o’clock, green, green, his colour, side of the sun, right round the sun, greenie colour and red colour. Sometimes they tell us: that’s a danger. People can see, and get sick. When you see that greenie colour and red colour, that’s no good. Something, he mean, he mean something, sometime you can see, it’s like a last day. Before you’re dead, you can see that greenie colour and red, And you’ll be gone. Get weak and sick. That’s the way they used to tell us. Story. Sometime, morning time, red sun getting up, early morning. Or sometimes he go down red: red morning time, red afternoon time. That’s no good. That’s a danger. They mean something. Or you can see last day. Red, every day, every morning, every afternoon, red sun, that’s danger. Or sometimes you can see, dinnertime, red every day and every morning. Or sometimes, big wind, they used to tell us, wind coming from south, wind blowing from south-west, every day, every day and every night, that means something. That’s other danger.

Might be three months over, wind coming from same place, that’s a danger. He mean something — that’s the last day, they used to tell us. When you feel that wind coming, every day from south-west, day and night, wind blowing, strong wind, that’s no good, that’s danger, he mean something, that’s the last day. They know, they bin know, long time ago. All them wind, and sun. They bin know what he mean, that’s the last day. They used to tell us.

Another thing they tell us — what you see, dinner time, when he get dark. That’s danger again. Dinner time he get dark, you can’t see anything, no light, that means something, because they used to do, Aborigine man used to do, something, blackfella, they make? They makim dark. Dinnertime there can be no light. They used to make everything dark. They used to tell us all them story.

Another one — big star. They used to tell us, big star. Big star. Aborigine man can makim come down big star. Big star. He can fall in the ground. They used to tell us, they can make star. Big star can fall in the land, he can kill all the people. Aborigine people used to have everything. He can come down star. They used to tell us story. But not now. [Long pause].

And big cold wind, from north-east. That’s a danger. It can kill the people. They used to tell us, looking after fire, for winter time. Winter time is no good. Rain, and big wind, that’s for winter time, mean kuluwa. Danger. They callim makurru and jarrinyinyi. Makurru and jarrinyinyi mean winter time. Cold.

They used to look after big fire. That’s winter time. Kuluwa time. They used to tell us, you’ve got to lookin after your firestick. Makim mangkaja. When he get wet, you got to put everything in a mangkaja. Mangkaja means little house. That’s the way they used to tell us, in the bush.

They used to tell us, don’t go to that cave, he got something in the cave. He got a man there, in the cave, maneater. Don’t go there, he might eat you, put you under the cave. They used to tell us story, we can’t find you kid. Don’t go in that cave. He got something there. He got a man, bald head, no hair, clean, clean like sand. That man look like sand. He live in the cave. They callim name, Mantamarta. Mantamarta, he’s a bald head. If he grabim anybody, he take them down, under the cave. He clean his hair, everything. But he won’t kill him. Or sometimes, he can eat it, when he feel hungry. That’s what they call Mantamarta.

He living in a cave, all the time. Sometimes people don’t walk there, near, the cave. Or sometimes you can walk around there. Long as people don’t want to make noise. You can walk in quiet, and have a look. You can see that track, Mantamarta track, and you can seeim big cave there, or sand. You can smell that ground, he different smell, powerful one. He’ll make you sick. Sick and weak. That’s Mantamarta. Mantamarta and Jingkajarti. That’s a bit of a man. Jingkajarti, they callim. He’s got a white spot on his forehead. That mean Jingkajarti. He’s like a dog, big dog. Maneater. He’s living in a cave again. Cousin to Mantamarta. Jingkajarti. They used to tell us, don’t go that place. He got a big mob Jingkajarti there. Some sort of animal. Maneater. They used to tell us, don’t go over there. Don’t go looking round the cave. Mostly, bush area. Desert area. They get plenty animals there. Mantamarta and Jingkajarti. They use to tell us, don’t walk around self.

Jilji, Jimmy Pike, Walmajarri people. AIATSIS ATS1036_095

Jilji, Jimmy Pike, Walmajarri people. AIATSIS ATS1036_095

Jila Japingka: Birthplace of an artist

Jimmy Pike was born near Jila Japingka a major waterhole around 400 kilometres south of Fitzroy Crossing in the Great Sandy Desert. Jila are desert soaks that never dry out. The word ‘jila’ is often translated by desert people as ‘living water’, indicating the importance of these sites.

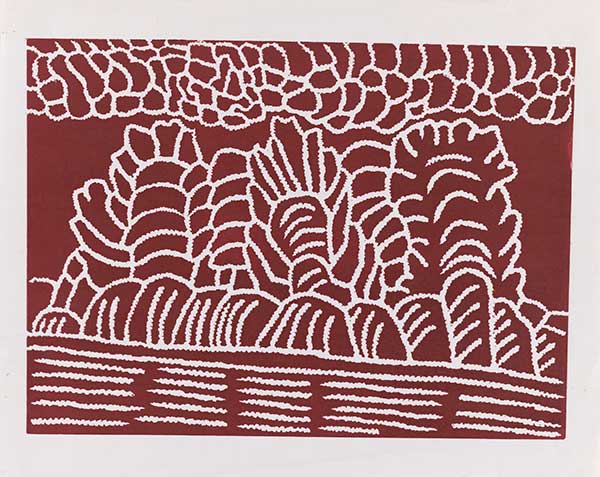

Jila Japingka is a significant subject in Pike’s artwork and appears in many prints and drawings, including some of his earliest prints: Japingka Waterhole, Dreamtime story (I) and (II).

Pike also created artworks depicting the spirit who lives at Japingka. Fellow Walmajarri artist Peter Pijaju Skipper has described Japingka as:

Japingka is a big jila. It’s the main waterhole for my Country; my father’s Country, my grandfather’s Country. It’s a big Law place. People used to meet there in hot weather, before rain. They did ceremonies there. I used to go there with my family when I was a boy.

Jimmy Pike - Lowe, P 2007, In the desert: Jimmy Pike as a boy, Penguin Books, Camberwell, pp 59–60.

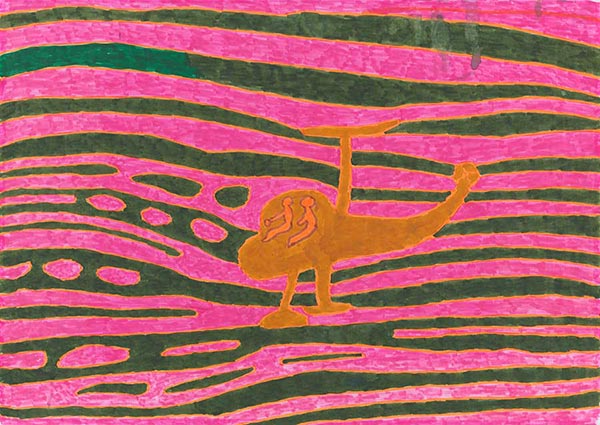

In the late 1980s, Pike and Pat Lowe collaborated with director John Tristram to create the documentary The Quest of Jimmy Pike (1990). Filmed at Kurlku, other locations in the Great Sandy Desert and Fitzroy Crossing the documentary captures Pike’s attempts to return to Jila Japingka with members of his family who had not visited this important site for decades. Unable to make the journey by car or on foot, Pike flew there by helicopter across the desert sand hills.

Helicopter over the desert near Japingka, Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_267

Helicopter over the desert near Japingka, Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_267

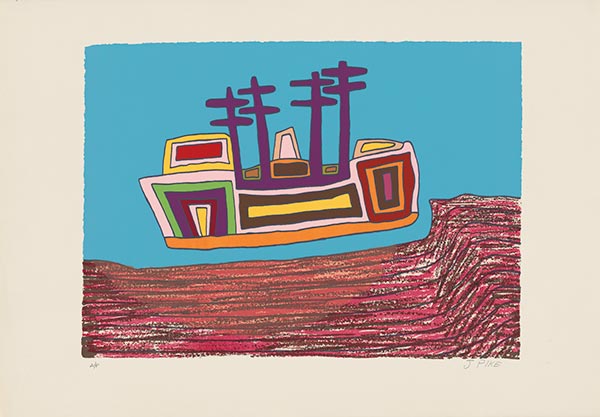

Japingka Waterhole - Dreamtime story I, Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_328

Japingka Waterhole - Dreamtime story I, Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_328

First impressions: Pike's early prints

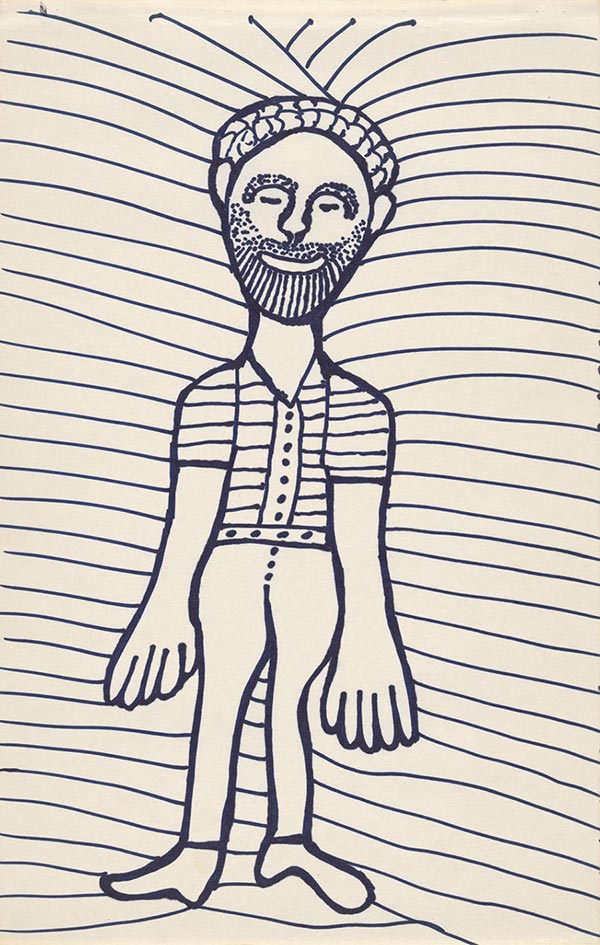

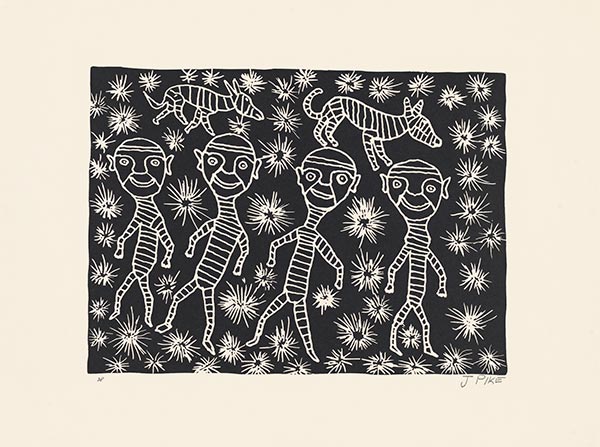

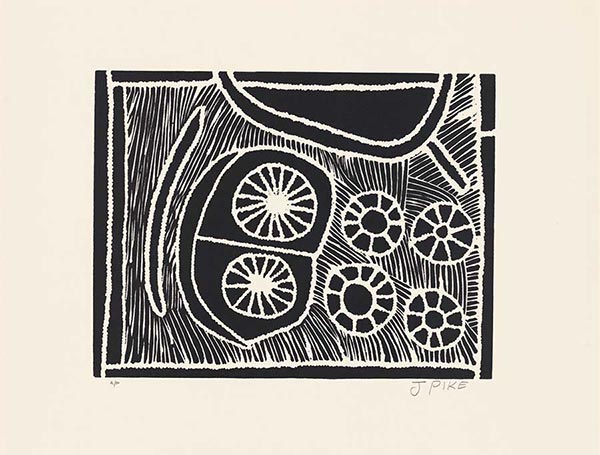

Jimmy Pike first explored felt-pen drawing and linocut printing in the early 1980s. As an inmate at Fremantle Prison, Pike attended art classes organised by Stephen Culley and David Wroth, who would later establish Desert Designs.

The Jimmy Pike collection includes more than 30 of Pike’s linocuts, offering a rare insight into some of his earliest artworks. Produced mainly in black and white, Pike’s early linocuts show an artist confidently experimenting with new media to represent his desert country.

Pike carved his lino with uneven zigzag lines a technique similar to carved boab nuts a practice common in the Kimberley region. The deep cutting of Pike's lino meant that they were often too fragile for subsequent editions; later copies were either produced as screen-prints or not at all, making many of these early linocuts very rare.

Life in the desert: Pat Lowe and Jimmy Pike

In 1986 Jimmy Pike was released on parole to a desert camp with members of his family at Kurlku on the edge of his country in the Great Sandy Desert. That same year Pat Lowe, a British born psychologist who had met Pike in Broome Prison in the late 1970s, joined the artist at Kurlku as his partner and collaborator.

Pat’s Story, Husband and wife and their dog and Rockhole Desert Country are some of the drawings that document Pike and Lowe’s life in the desert. Their co-written publication Jilji: Life in the Great Sandy Desert (1990), which was republished in 2012 as You Call It Desert – We Used to Live There, shares Pike’s desert knowledge and artworks along with Lowe’s experiences as a newcomer living at Kurlku. In their first year living in the desert Pat experienced uncomfortable spinifex sores on her legs, which Pike correctly informed her would not return after the desert got to know her.

From 1990, until Pike passed away in 2002, the couple were based in Broome, from where they could both visit the desert and travel internationally to attend exhibitions of Pike’s art.

Jina (footprints) 'Husband and wife and their dog', Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_203

Jina (footprints) 'Husband and wife and their dog', Jimmy Pike

ATS_1036_203

Desert designs: International fashion

In the mid-1980s, Jimmy Pike licenced many of his artworks to Desert Designs, a concept marketing company established by art teachers Stephen Culley and David Wroth. Culley and Wroth had met Pike through their art lessons in Fremantle and Canning Vale prisons. Their collaboration launched Pike as an international artist. Desert Designs produced prints, textiles, clothing and homewares featuring Pike’s bold artworks of his desert country, which embodied the colourful and expressive spirit of 1980s global fashion. Desert Designs was also a leader in the ethical marketing of Aboriginal art, promoting the artist’s name as well as labelling items with a copyright notice and information about the artwork and its meaning.

Desert Designs continued to incorporate Pike’s artwork into their products until they ceased trading in 2020. Their royalties supported other artists through the Jimmy Pike Trust.

Country in colour: The Great Sandy Desert

Pike’s brilliantly coloured artworks depict his desert home brimming with life, countering any notion of the desert as a barren or desolate place. Ngarrangkarnijangka (spirit beings) occupy many drawings in the Jimmy Pike collection and jilji (sandhills), partiri (flowers) and pamarr (rocks) are recurring subjects that highlight the diversity of the environment in the Great Sandy Desert.

Partiri Jiljikarraji Turtapungany Kujartijiliny, Jimmy Pike

ATS1036_265

Partiri Jiljikarraji Turtapungany Kujartijiliny, Jimmy Pike

ATS1036_265

Country Desert Flowers after rain and sandhills, Jimmy Pike

ATS1036_239

Country Desert Flowers after rain and sandhills, Jimmy Pike

ATS1036_239

The Jimmy Pike collection

Walmajarri country is vibrantly presented in acclaimed and prolific artist Jimmy Pike’s collection of drawings, prints, and paintings held at AIATSIS.

Donated in 2016 by Pat Lowe, the artist’s wife and long-time collaborator, the collection includes over 440 individual artworks, many adapted by Desert Designs in the 1980s and 1990s into internationally renowned fashion.

The Jimmy Pike collection offers insight into the life of an artist deeply connected to his country in the Great Sandy Desert.

AIATSIS would like to thank Pat Lowe and Peter Murray, CEO, Yanunijarra Aboriginal Corporation, for their support of this online presentation.