This month marks 35 years since the Federal Government ceased the Hydro-Electric Commission’s construction of a dam on the Franklin River in southwest Tasmania following a High Court of Australia ruling; however, evidence presented during this court case claiming the archaeological significance of Kutikina Cave was neither exceptional nor significant continued to haunt archaeologist Rhys Jones. Despite the High Court ruling, Jones believed there was an urgent need to undertake further archaeological investigations to document the significance of other cave sites in the area.

In doing so, the scene was set for Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS) film maker Kim McKenzie to document and produce a film about these archaeological investigations under the working title of the “Tasmanian Film Project". By 1983 McKenzie had been employed with the AIAS Film Unit just shy of a decade. During this time McKenzie directed and produced Waiting for Harry (1980)—a film that documented negotiations by Anbarra elder Frank Gurrmanamana and anthropologist Les Hiatt, whilst waiting for fellow elder Harry Diyama in the lead up to a funeral ceremony for Frank’s brother.

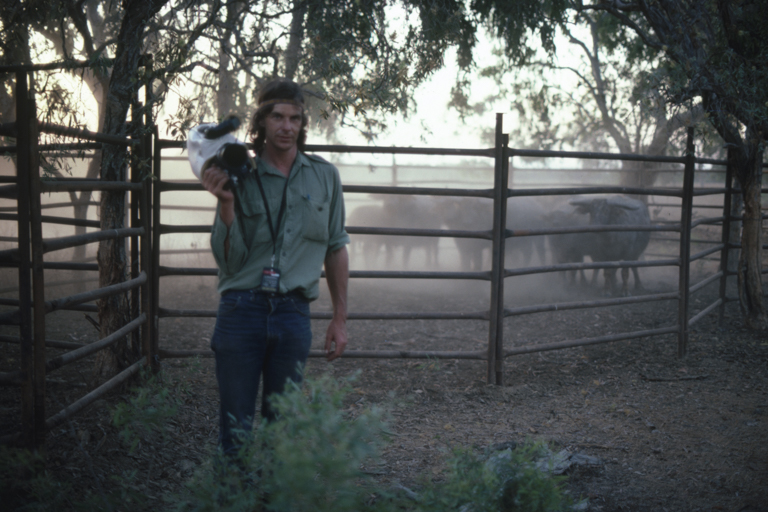

Kim McKenzie during the filming of AIAS film Something of the Times (1985), Annaburroo Station N.T. (1985, Robert Levitus, AIATSIS, LEVITUS.R02.CS-000087376).

Kim McKenzie during the filming of AIAS film Something of the Times (1985), Annaburroo Station N.T. (1985, Robert Levitus, AIATSIS, LEVITUS.R02.CS-000087376).

In describing the focus of the film itself, McKenzie (1995 in Bryson 2002:67) recalls how:

My memory of that shoot involves a dramatic change part way through the filming. That change was seeing the direction the film would take…What brought about the change was everybody’s increasing worry that the ceremony might not come together and reach a conclusion. We all shared this worry, and it seemed there was a real chance that it might all come to nothing…Instead of just sharing the concerns, I began to film them.

To document these concerns in the lead up to the funeral ceremony—rather than the ceremony itself—was a distinctly different approach to ethnographic film making, but one that exemplifies why Waiting for Harry won the 1982 Royal Anthropological Institute Film Award for “the most outstanding film on social, cultural and biological anthropology or archaeology” (Ronin Films 2018). The film itself would go on to become one of AIATSIS’ most popular productions and launched McKenzie to prominence as a film maker (Bryson 2002:67).

The Tasmanian Film Project

The “Tasmanian Film Project” would not be the first time McKenzie had produced a film with archaeology as a central theme, having directed the film The Spear in the Stone (1983), which also featured Rhys Jones as well as anthropological geneticist Neville White and Yolngu community members. It was likely no coincidence that McKenzie envisioned the “Tasmanian Film Project” would be a sequel of sorts to The Spear in the Stone; during filming for The Spear in the Stone in 1981, Jones was also involved in excavations of Kutikina Cave in Tasmania. Given this excavation occurred in light of the highly publicised controversy surrounding the Hydro-Electric Commission’s proposed dam, it comes as no surprise that the “Tasmanian Film Project” sought to explore the broader context of archaeological investigations.

There is little doubt, however, that the archaeological investigations to be documented in the “Tasmanian Film Project” were undertaken in the shadow of another film featuring Rhys Jones: The Last Tasmanian. This film stirred controversy when it was released in 1978 and was attacked for denying Tasmanian Aboriginal people’s existence.Given the “Tasmanian Film Project” was never produced into a film for general release, it’s worth pondering whether the public was ready for another film about Tasmania.

It was also anticipated that the archaeological investigations featured in the “Tasmanian Film Project” would make some sort of interesting archaeological discovery. Jones and Allen (1984:95) reflect upon the contribution a site of this nature would have contributed to archaeological knowledges more broadly:

… [the area surveyed] is not conducive to the formation of the caves suitable for human occupation. This is highly regrettable since the discovery of Pleistocene occupation in limestone caves so close to the edge of the southern continental shelf of Australia would have been potentially of immense interest for the prehistory of coastal adaptation in this part of the world.

It is possible that McKenzie also anticipated such a discovery as an outcome of these archaeological investigations; a discovery that would create a dramatic change that could be capitalised upon for the final production of the “Tasmanian Film Project”, following a similar trajectory that occurred during the production of Waiting For Harry (McKenzie in Bryson 2002:67). Without such a discovery, however, the direction of the “Tasmanian Film Project” remained unclear and as a result this may have also contributed to the film remaining unproduced.

Despite this, almost 9 hours of archival footage from these archaeological investigations exists. Whilst this footage does not feature nor reference the broader context as McKenzie envisioned, it does provide insights into the challenging nature of these archaeological investigations some 35 years after it was recorded. For a detailed description of this footage, please refer to the Finding Aid for this collection.

References

AIATSIS 2016 Film. AIATSIS collection, accessed October 5, 2016

Bryson, Ian 2002 Bringing to light: a history of ethnographic filmmaking at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra

Jones, R. and J. Allen 1984 Archaeological Investigations in the Andrew River Valley, Acheron River Valley and at Precipitous Bluff, southwest Tasmanian, February 1984. Australian Archaeology

Leigh, M. 2016 Australian Ethnographic Film. Electronic document, accessed October 5, 2016

Ronin Films 2018 AIATSIS Collection: Waiting for Harry accessed October 5, 2016