Father Dixon and the Stuart case papers

On 10 May 1959, Catholic priest Father Tom Dixon visited Arrernte man Rupert Max Stuart at the Adelaide gaol with the expectation of preparing the prisoner for execution twelve days later.

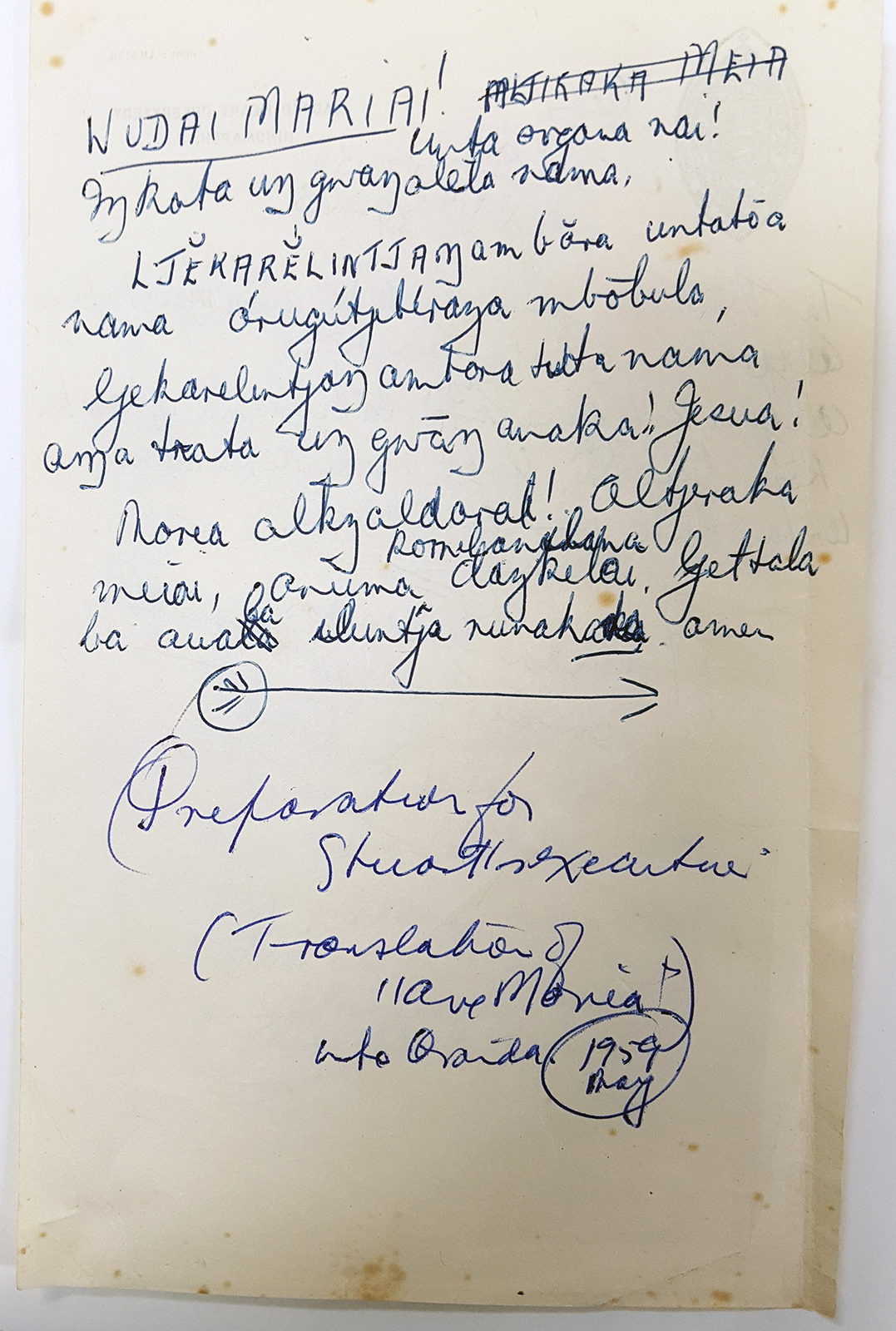

A chilling reminder of this visit is captured in Dixon’s hand scribbled note titled ‘Wudai Mariai’ that is in the Father Dixon and the Stuart case papers held in the AIATSIS Collection. The note contains the following annotation: ‘(Preparation for Stuart’s execution) (Translation of Ave Maria into Aranda May 1959)’.

Father Dixon created the Hail Mary note after meeting Stuart in the hope that it would provide some comfort as he accompanied Stuart to the gallows. Stuart had just heard that an appeal to the criminal court had failed.

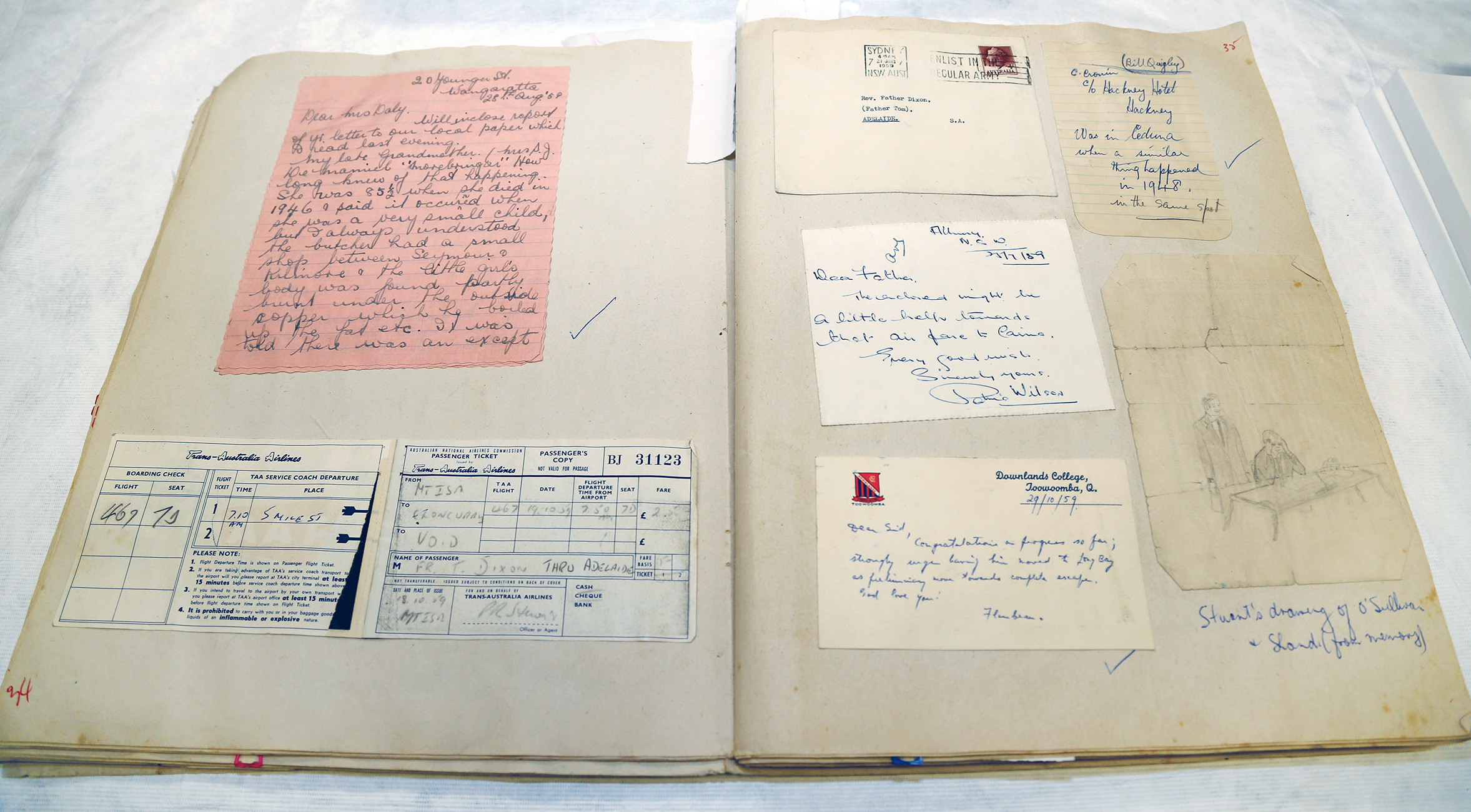

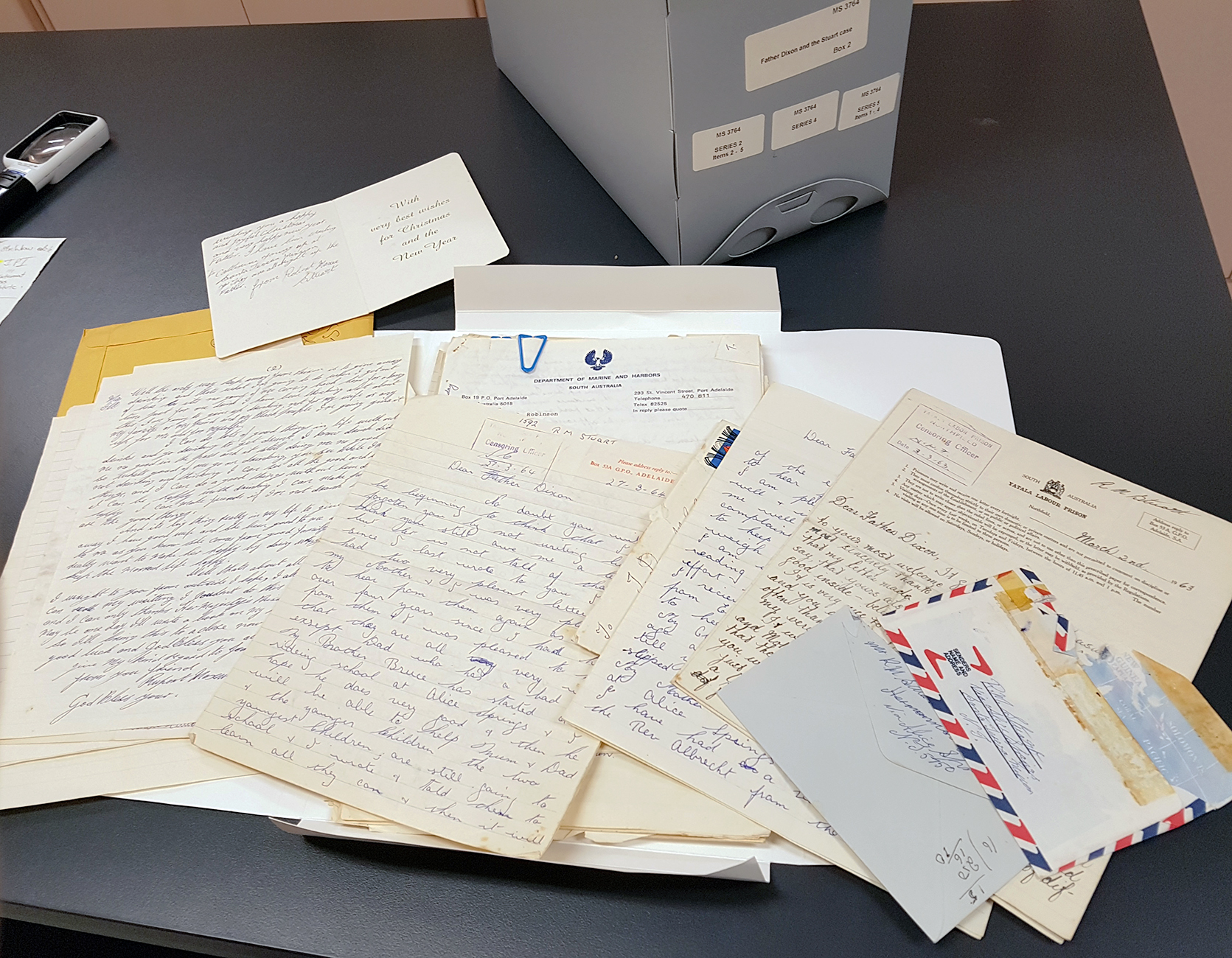

The Dixon and Stuart Case Collection 1958-1987 contains hand written diaries, court transcripts, correspondence, pencil drawings, a sound recording, newspaper clippings and the manuscript for the book ‘The Wizard of Alice’ authored by Father Dixon.

The collection provides an insight into the campaigns, networks and protagonists whose combined efforts resulted in the eventual commutation of Stuart’s death sentence to life in prison.

About the case

Stuart was sentenced to hang in April 1959 for the murder of nine year old Mary Hattan in December 1958 in Thevenard (near Ceduna, SA).

Stuart's conviction was challenged through the Australian courts and ultimately the Privy Council in London, all of which upheld the original conviction.

Petitions were presented to the Executive Council requesting the commutation of Stuart’s sentence and elements of the case were subject to a Royal Commission inquiry which also held that a miscarriage of justice had not occurred.

Stuart was convicted largely on the basis of a signed confession which he claimed had been beaten out of him. Father Dixon notes in his diary that he came to believe that Stuart could not have dictated the confession in the manner asserted by police in the original trial.

Dixon sought the help of anthropologist/linguist Ted Strehlow who undertook the first ever forensic linguistics analysis of Aboriginal English against Standard Australian English (SAE). The analysis showed that Stuart could not have spoken the words in the confession. For a full discussion on the linguistic importance of this case see Eades (2013). Copies of this material as well as a commentary by Strehlow reflecting back on the Stuart Royal Commission penned in 1972 can be found in the Collection.

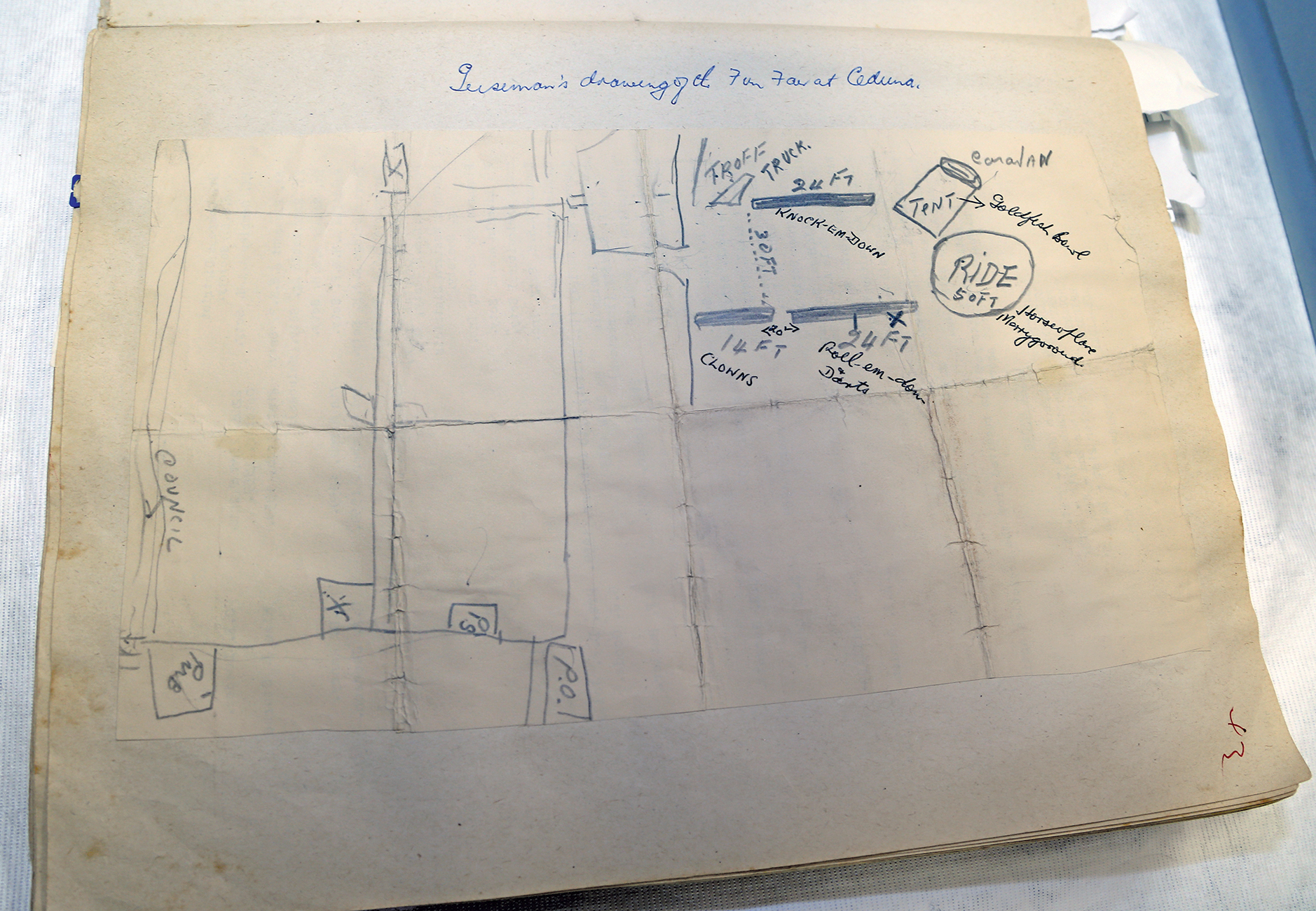

At the time of the murder, Stuart worked at a travelling Fun Fair at Ceduna owned by Edna and Norman Gieseman. The Giesemans had not been interviewed by police in relation to Stuart’s whereabouts on the day of the murder.

Father Dixon flew to Queensland and obtained affidavits from them which provided an alibi for Stuart. The trip was funded by Rupert Murdoch’s The News after its editor Rohan Rivett met with Father Dixon.

The Gieseman affidavits as well as Strehlow's forensic linguistics analysis were presented to the Royal Commission, however they were never tested before a jury.

A copy of the plane ticket used by Dixon to travel to Queensland, copies of the Gieseman affidavits and a hand drawn sketch of the Ceduna Fun Fair layout made by Norman Gieseman are part of this collection.

Pencil drawing of Ceduna Fun Fair layout. According to the Giesemans, Stuart was working the dart stall at the time the murder was committed. AIATSIS Collection, MS 3764, Series 3, Item 3, p. 43.

Pencil drawing of Ceduna Fun Fair layout. According to the Giesemans, Stuart was working the dart stall at the time the murder was committed. AIATSIS Collection, MS 3764, Series 3, Item 3, p. 43.

The Royal Commission into the Stuart Case was established by the Playford Government in July 1959. Prior to this, the government had rejected petitions from The Howard League for Penal Reform and the Aboriginal Australian Fellowship to commute Stuart’s sentence to life.

The establishment of the Royal Commission was an attempt by the government to stem the tide of public opinion against it and the unrelenting media activism on the part of Rohan Rivett and Rupert Murdoch regarding the Stuart case, capital punishment and the Adelaide establishment.

The Royal Commission came under criticism for its narrow terms of reference and the commissioners that were appointed; the chair, Chief Justice Sir Mellis Napier had presided in the hearing of Stuart’s appeal and Commissioner Mr Justice Reed was the original trial judge.

On 31 July 1959, the following cartoon by Norm Mitchell appeared in the News alongside an editorial that proclaimed: ‘There’s Still a Long Way to Go!’ It suggests that a fair outcome could not be achieved when two out of the three judges had already publicly asserted their opinions on the case.

On 5 October 1959, two months before the handing down of the Commission’s findings, South Australian Premier Sir Thomas Playford commuted Stuart’s sentence to life imprisonment.

A highlight of this collection is the correspondence from Stuart to Father Dixon during the period 1964 to1983. Stuart learnt to read and write while in prison and his thoughts on this achievement, family pride, concerns and gratitude towards those that helped him are topics that he returns to often.

Stuart was an accomplished artist and one of his drawings, which he created during the Royal Commission, remains in the AIATSIS Collection. It is a portrait of Mr JD O’Sullivan (Stuart’s solicitor in the Supreme and High Court) and Jack Shand QC (defence council of the Privy Council and the Royal Commission).

Pencil drawing of Mr JD O’Sullivan (the solicitor that represented Stuart in the Supreme and High Courts) and Stuart Shand QC (defence council of the Privy Council). AIATSIS Collection MS 5013, Series 3, Item 3, courtesy of the Stuart Family.

Pencil drawing of Mr JD O’Sullivan (the solicitor that represented Stuart in the Supreme and High Courts) and Stuart Shand QC (defence council of the Privy Council). AIATSIS Collection MS 5013, Series 3, Item 3, courtesy of the Stuart Family.

The Stuart case received much media attention, triggered political debate and attracted support from a diverse range of people and organisations.

These themes are documented in two scrapbooks containing newspaper clippings from the period 1959 to 1984 and a scrapbook containing correspondence from the central characters involved in the case as well as the numerous Australians who provided moral and monetary support for the campaign to commute Stuart’s sentence.

While much has been published on the Stuart case, some of the original material in this collection has not come to light before.

Stuart served 14 years in prison and went on to become a highly respected elder who initiated Charles Perkins into Arrernte law, a land rights activist in Alice Springs, a campaigner against the opening of the Strehlow Centre, founder of the Yeperenye Festival and chair of the Central Land Council (1998-2001). He passed away on 14 November 2014.

Rita Metzenrath discusses the Stuart case and the materials associated with the case that are now in the AIATSIS Collection.

More about this item

Further reading and resources

References

Cockburn, S 1972 Rupert Max Stuart: a case history, The Canberra Times, 9 September, p. 11.

Aikman, A 2014. Death of Max Stuart. Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, 24 November, 2014.

Chamberlain, Sir Roderick 1973. The Stuart affair, Rigby, Adelaide.

Central Land Council 2014. Late CLC chair’s land rights fight as urgent now as during his lifetime.

Eades, Diana 2013. Aboriginal English on Trial: the case for Stuart and Condren in Aboriginal ways of using English, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, pg 130-158.

Inglis, Ken 2002. The Stuart Case, Black Inc, Melbourne.

Lahiff, C et. al 2005. Black and White, Home Vision Entertainment, Chatsworth, California.

Middleton C 2017. Norm Mitchell and cartoon politics in the ’70s, The Centre of Democracy, Adelaide.

South Australia. Royal Commission in regard to Rupert Max Stuart 1959, Report of the Royal Commission in regard to Rupert Max Stuart, Government Printer, Adelaide.

Whitton, E 2016. Rupert Murdoch: Our Part in His Evil Upfall.