'Keriba gesep agiakar dikwarda keriba mir. Ableglam keriba Mir pako Tonar nole atakemurkak.' — Bua Benjamin Mabo, Meriam linguist

The land actually gave birth to our language. Language and culture are inseparable.

Kari ‘Apura werut’, pako Yobo Ad ide kari able Mir nakwari.’ — Lillah Noah, Meriam Elder

My mother’s tongue and Father God gave me this language.

Languages have always been here

In the time of creation, ancestral beings spread across the continent creating all landforms, plants, animals and humans. These beings, which took many different forms, established societies and the laws for living, the languages, customs and ceremonies.

'Yuwayi ngajuju Jungarrayi, Jungarrayi Simms kardiya kurlangu yirdiji Otto Simms but Jungarrayi yuwayi from the clan group Japaljarri/Jungarrayi Jukurrpa nyampu kankarlarra yiwarra yurlpararri ngaju nyangu jukurrpa ngaju nyangu kirda nyanu kurlangu jukurrpa, warringiyi kirlangu yuwayi the milky way jukurrpa nganimpa nyangu yuwayi.' – Otto Jungarrayi Simms, Walpiri

I am Otto Jungarrayi Simms, Jungarrayi from the clan group Japaljarri/Jungarrayi. My Dreaming is the milky way, my Dreaming and my Father’s and my Grandfather’s, our Dreaming is the milky way.

Many languages

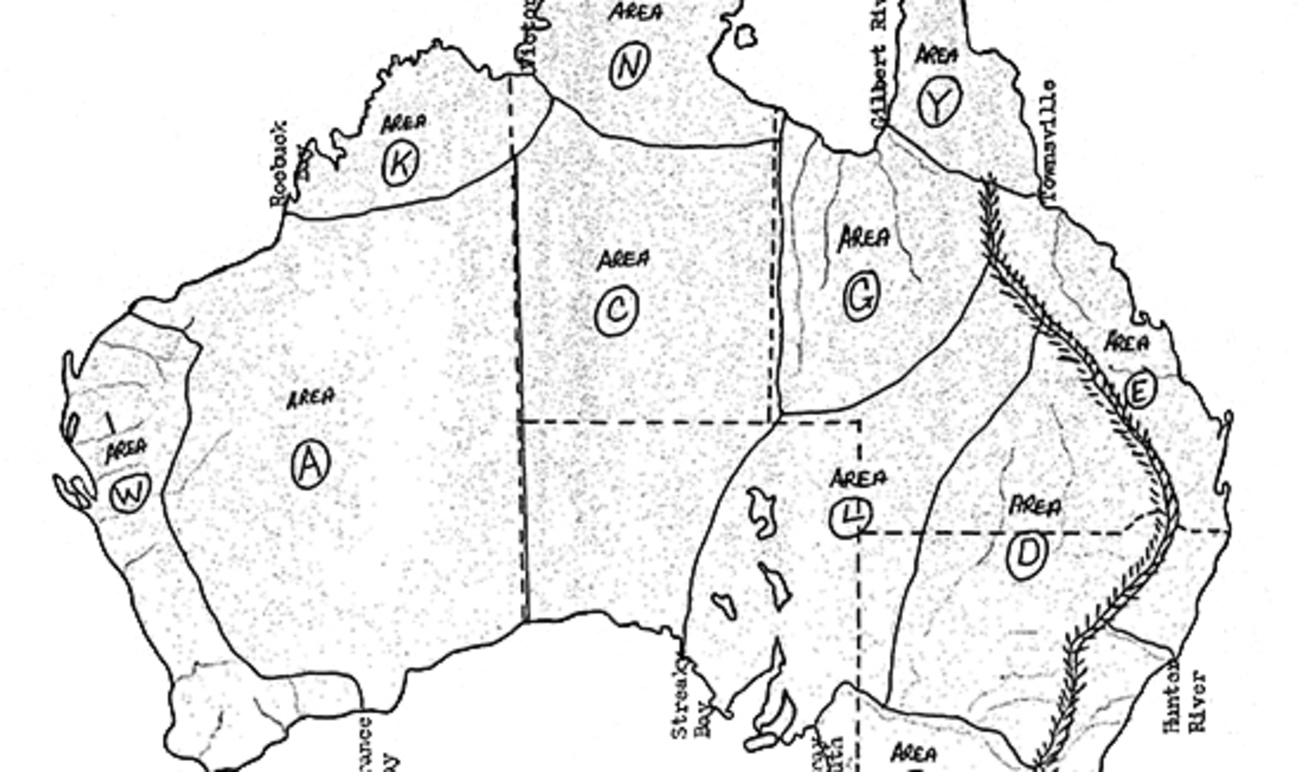

In Australia there are more than 250 Indigenous languages including 800 dialects. Each language is specific to a particular place and people.

In some areas like Arnhem Land, many different languages are spoken over a small area. In other areas, like the huge Western Desert, dialects of one language are spoken.

In the Torres Strait three main languages are spoken:

- Kala Lagaw Ya is spoken on the western islands of Mabuiag and Badu.

- Meriam Mir is spoken throughout the eastern islands of Erub (Darnley Island), Ugar (Stephen Island) and Mer (Murray Island).

- Yumplatok, also known as Torres Strait Creole, is spoken in the Torres Strait and in some parts of Cape York Peninsula.

As of 2006 it was estimated that there were just over 200 Meriam Mir speakers.

Watch a video of Meriam Mer Elders describing the importance of keeping the Meriam Mir language strong.

Language is survival

'Kaji yimi ngalipa nyangu pirrjirdi karri, ngulaju ngalipaju kapurlipa wankaru nyina Warlpiri patu yapa. Ngalipa nyangu yimingki ka ngalpa pirrjirdi mardani. Kuja juku ka ngalpa pirrjirdi warrarda mardani.' — Theresa Napurrurla Ross, Warlpiri

If our language survives, we survive as Warlpiri people. Our language keeping us strong. It’s always kept us strong.

Warlpiri translator Theresa Napurrurla Ross with granddaughter Bethalia Kelly. We know that educational outcomes improve when children are taught in their first language, especially in the early years.

Warlpiri translator Theresa Napurrurla Ross with granddaughter Bethalia Kelly. We know that educational outcomes improve when children are taught in their first language, especially in the early years.

Warlpiri is a central Australian language spoken primarily in the communities of Yuendumu, Lajamanu, Nyirripi and Willowra.

The 2006 Census recorded just over 2500 speakers, making it one of the most spoken languages in Australia in terms of number of speakers.

Watch a video of Theresa Napurrurla Ross and Jimmy Langdon talking about how the Warlpiri language is connected to everything.

Language is identity

'Language is part of our songlines, stories, spirituality, law, culture, identity and connection. Language transfers important knowledge passed down from our Ancestors and Elders that guides us.' – Lynnice Church, Ngunnawal

Language is more than just a means to communicate, it is what makes us unique and plays a central role in our sense of identity. Language also carries meaning beyond the words themselves. It is a platform which allows us to pass on cultural knowledge and heritage. Speaking and learning first languages provides a sense of belonging and empowerment.

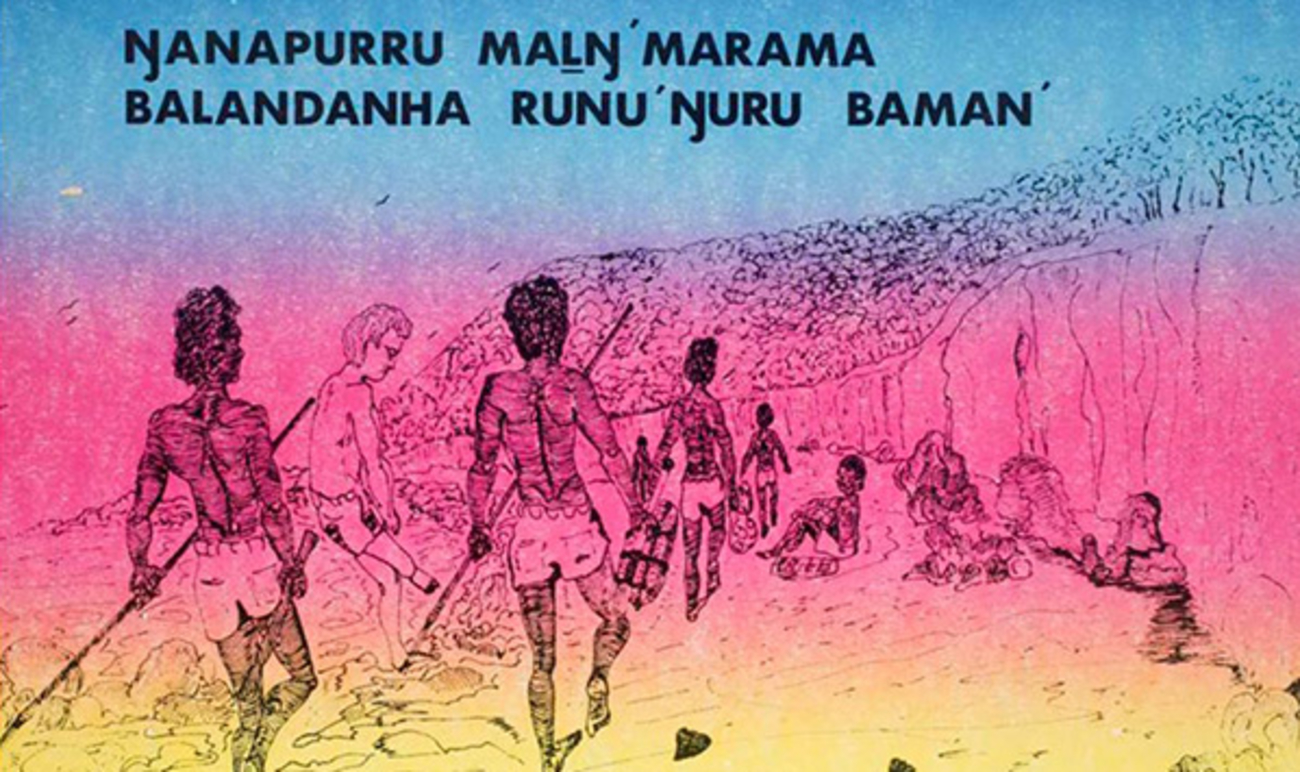

Reviving language

Past government policies which saw people moved onto missions and children removed from families had a devastating impact on the transmission of languages and culture. In many communities the link between generations of speakers was broken and children had little or no knowledge of their first languages. Their parents were partial speakers and their grandparents were the remaining few speakers of a language that, as the Elders, they alone could pass down to the next generation.

For others the threat of being taken away from their families meant that language was kept secret.

'When I was a child we had to keep our language secret. Today we are relearning some of our language – ensuring that we the Ngunnawal are the knowledge keepers of our language.' — Caroline Hughes, Ngunnawal Elder

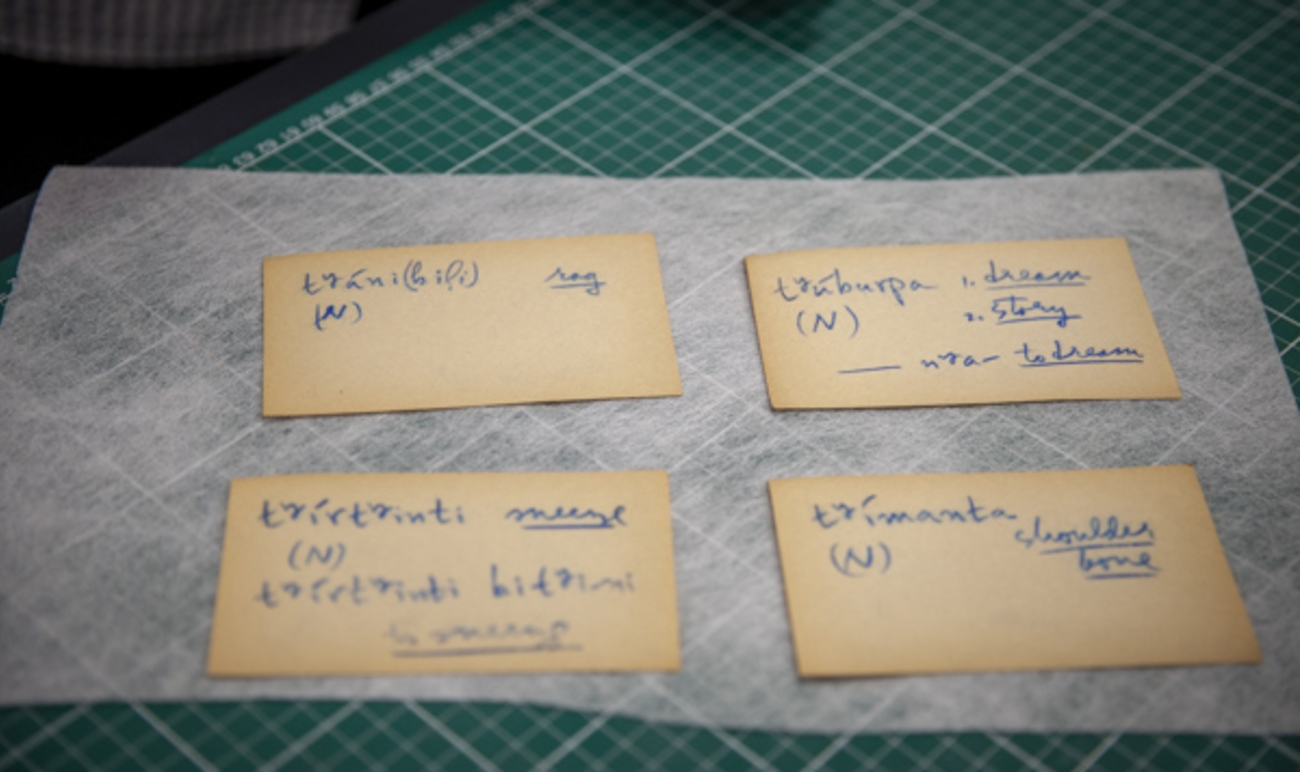

While languages may have been lying dormant they are never lost. By drawing on the memories of Elders and historical records, languages are being recovered and revitalised for future generations.

For almost a century, the Ngunnawal language had not been spoken fluently. Today the Ngaiyuriija Ngunawal Language Group, comprised of a number of Ngunawal family groups are revitalising their language, finding words thought lost, rediscovering language through journals, tapes and the few words held and shared by Elders.

'Our Ngunnawal language links family and community to our homelands. Our language is the key to all our relationships and how we interact with each other.' - Caroline Hughes, Ngunnawal Elder

Ngunnawal acknowledgment

Ngunnawal Elder Jude Barlow gives a Welcome to Ngunnawal Country.

In Port Headland, Western Australia, the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre preserves, promotes and maintains around 31 Aboriginal languages across the Pilbara.

Today it holds a unique and diverse cultural collection including 5000 recordings of Pilbara languages in its archives.

'Karlkunaku tukulu palanga karlja mangungja pirlparranga jurlurr warrarn yinirrangu palarrangu muwarr rrangu.' — Bruce Thomas, traditional Mangala man and Chair, Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

A place of archive, you know. Archive culture, history and all that and it covers the whole Pilbara – songs, songlines, sites… it’s all in that story in the language.

Learn more about the work of the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre.

Language lives on

Being able to pass on language to future generations is central to keeping language, identity and culture strong. As Tyronne Bell, Ngunnawal Traditional custodian explains, ‘You can have the stories and knowledge passed down from the elders but without language your whole cultural identity is incomplete.’

Speaking in language is also a powerful connection to ancestral spirits.

‘I want to keep teaching it for future generations, especially my grandchildren. ‘Cause I go out on Wakka Wakka Country to the sacred places, and in our way we acknowledge our Creators, our Ancestor spirits that are back in the hills and the trees and the rocks and that helped create Wakka Wakka Country and put laws for our people to abide by. So now I can go back and teach my grandchildren to speak in Wakka Wakka tongue to the ancestors and spirit.’— Anita Dodd, Wakka Wakka

'Omaskir kikem Meriam tonarge obau, keubu e Meriam tonar odikair a umele Meriam tonartonar obau nerut tonar gesepge.' — Father Ron Day, Meriam Elder

A child will enter in, in the Meriam environment, and then leave the Meriam environment and come to the complex world.

There are currently twenty two Indigenous language centres around Australia for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to maintain, preserve and promote the diversity of their languages.