Please be aware that readers may find some of the language and content distressing. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from Charles Perkins are taken from A Bastard Like Me, (published by URE Sydney, 1975). All quotes from Ann Curthoys are from her diaries which are in the AIATSIS Collection.

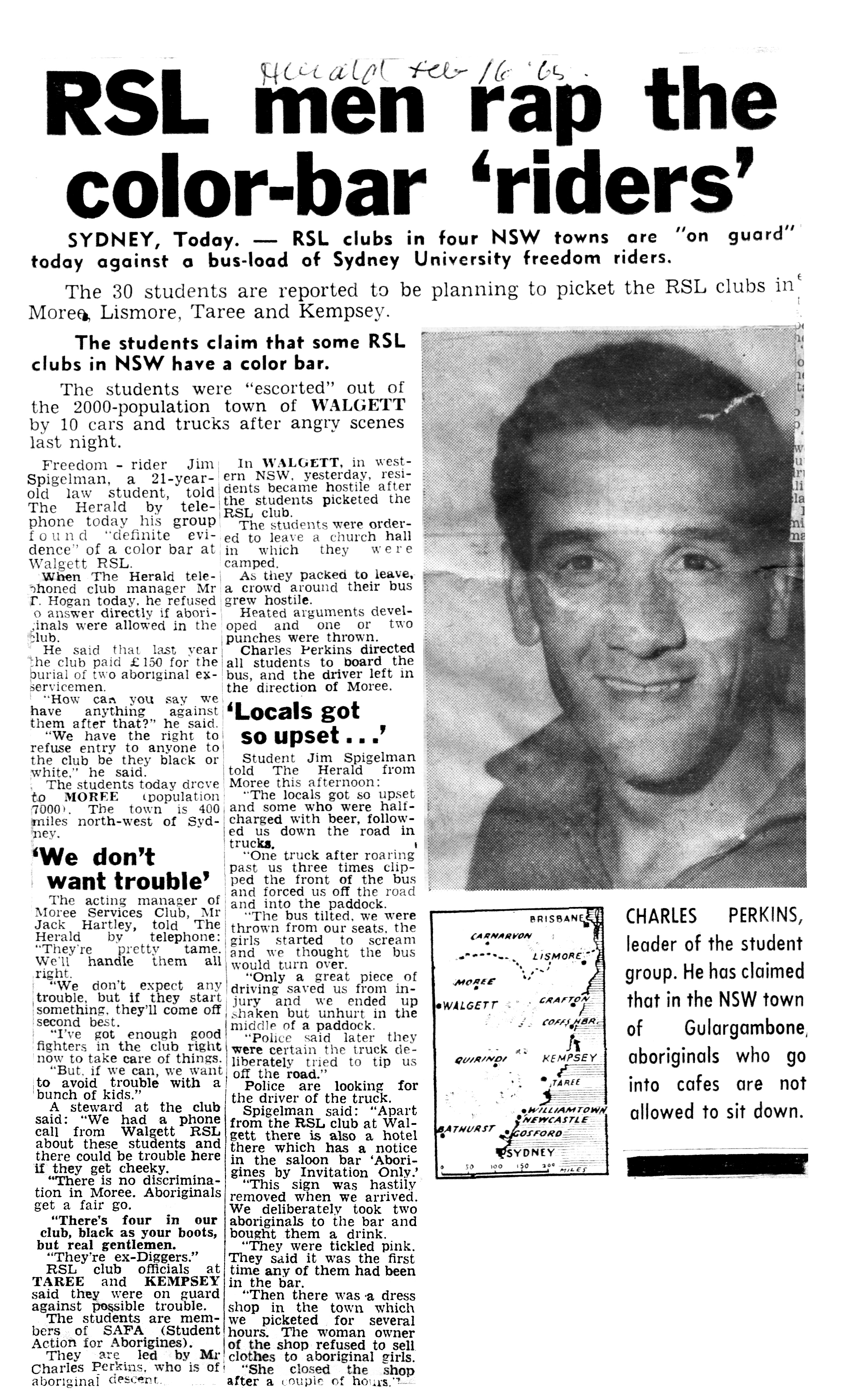

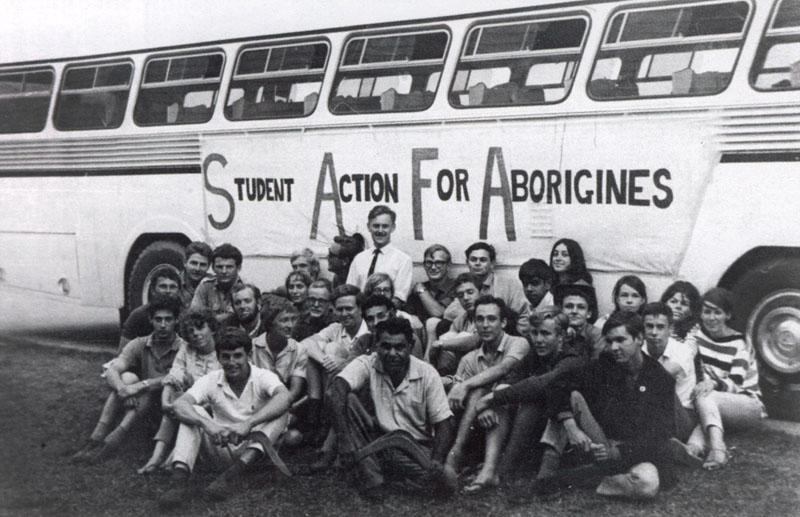

Spurred on by racial segregation in the United States of America, a group of students at the University of Sydney formed the Student Action For Aborigines (SAFA). Charles Perkins, one of only two Aboriginal students at the university at the time, was elected president of the newly-formed group.

Their mission was to shine a light on the marginalisation of Aboriginal people in New South Wales towns. During their fifteen day journey through regional New South Wales, the group would directly challenge a ban against Aboriginal ex-servicemen at the Walgett Returned Services League, and local laws barring Aboriginal children from the Moree and Kempsey swimming pools.

'The Freedom Ride was probably the greatest and most exciting event I have ever been involved in.' — Charles Perkins

'It was also a reaction to what was being done in America at that time. A number of students gathered together at Sydney University and thought that they might like to see a Freedom Ride eventuate here in Australia. They all put their sixpence-worth in, saying what should happen and what should not happen. No one had any precise ideas about it and we appealed to the Rev. Ted Noffs of the Wayside Chapel.' – Charles Perkins

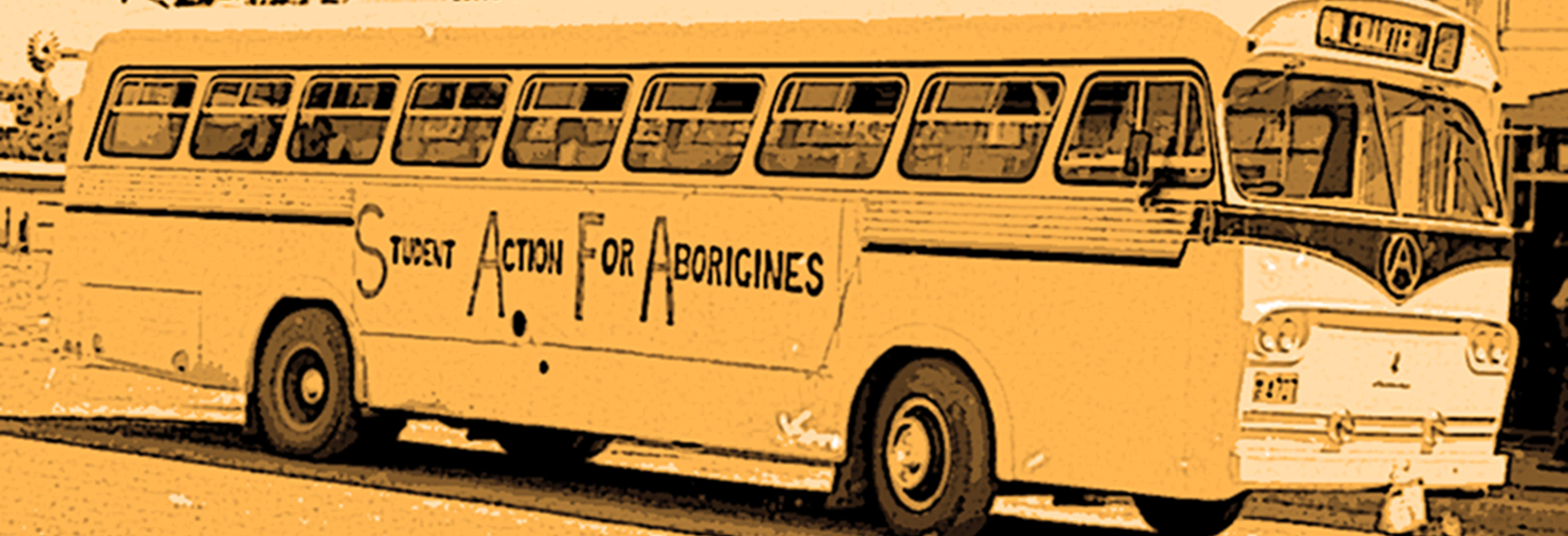

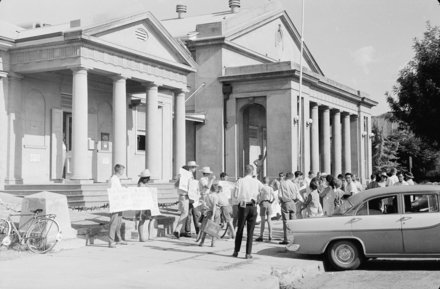

The SAFA group in front of their hired ‘Freedom Ride’ bus. Photograph reproduced with permission of Wendy Watson-Ekatein (nee Golding) and supplied by Ann Curthoys.

The SAFA group in front of their hired ‘Freedom Ride’ bus. Photograph reproduced with permission of Wendy Watson-Ekatein (nee Golding) and supplied by Ann Curthoys.

-

Meet the students

The students that made up SAFA came from many different existing Sydney University clubs and societies including the Australian Labor Party Club, the Newman Society, the Jewish Students Union, the Liberal Club, Jazz Society and the Civil Liberties Association. There were around 35 students that took part in the Freedom Ride. The majority of the students were aged nineteen with Charles Perkins being the eldest at twenty nine years of age.

Aidan Foy

Third-year Medicine, member of the Labor Club

Alan Outhred

Third-year Science, member of the Labor Club

Alex Mills

Third-year Theology, member of the Liberal Club

Ann Curthoys

Third-year Arts, member of the Labor Club

Ann’s diary provides much of the narrative of this story and gives us great insight into the day-to-day activities and experiences of the students during the Freedom Ride.

Barry Corr

Second-year Arts

Beth Hansen

Third-year Arts, member of the Humanist Society

Bob Gallagher

Third-year Engineering, member of the Labor Club

Brian Aarons

Third-year Science, member of the Labor Club

Charles Perkins

Arrernte man, born in Alice Springs, former soccer player, Aboriginal activist, third year Arts. President of SAFA and spokesman during the Freedom Ride.

Chris Page

Third-year Medicine

Colin Bradford

Third-year Science, member of the Labor Club

Darce Cassidy

Part-time third-year Arts, also ABC radio producer, member of the Labor Club

David Pepper

Second-year Arts

Derek Molloy

Third-year Arts

Gary Williams

Third-year Arts, Gumbaynggir man from Nambucca Heads

Hall Greenland

Third-year Arts, member of the ALP Club

Helen Gray

Second-year Arts

Jim Spigelman

Third-year Arts, leader of the Fabian Society, breakaway group from the ALP Club

John Butterworth

Third-year Science

John Gowdie

University of New England, son of Presbyterian minister from Dubbo

John Powles

Fifth-year Medicine, founder of the Sydney University Humanist Society

Judith Rich

Third-year Arts

Louise Higham

Second-year Medicine, member of the Labor Club

Machteld Hali

Second-year Arts, born in Holland, raised in Indonesia

Norm Mackay

Third-year Science, member of the Labor Club

Paddy Dawson

Third-year Arts, member of the ALP Club

Pat Healy

Third-year Arts, member of the Labor Club

Ray Leppik

Postgraduate Science

Rick Collins

Third-year Arts

Robyn Iredale

Fourth-year Arts, in Geography Honours

Sue Johnston

Fourth-year Arts, in History Honours

Sue Reeves

Third-year Arts, member of Abschol – a committee of the National Union of Australian University Students

Warwick Richards

Third-year Arts, member of the Student Christian Movement

Wendy Golding

Second-year Arts

ALSO ON THE BUS

Bill Pakenham

From Punchbowl, driver of the bus until Grafton

Ernie Albrecht

From Lugarno, driver of the bus from Grafton onwards

Gerry Mason

An older Aboriginal friend of Charles Perkins from Gerard government reserve in South Australia

The group ensured that their protests were covered by the media, bringing the issue of racial discrimination to national and international press attention and stirring public debate about the disadvantage and racism facing Aboriginal people across Australia at the time.

'The Ride was coordinated at the Wayside Chapel. The Chapel was going to be our contact with all the newspapers, television and radio. We did not think there would be much work involved but the Chapel was completely swamped. Ted was involved with the media and political figures and with the parents.' – Charles Perkins

The Ride

Saturday 12 February

Sydney: home of the Eora people

Well, we hired the bus. We placed a banner along the front and prepared to start off from Sydney. The Rev Ted said a prayer on the steps for those who like that sort of thing. I was one, I needed that kind of help. – Charles Perkins

Sunday 13 February

Wellington: home of the Wiradjuri people

'Houses of tin, mud floors, very overcrowded, kids had eye diseases, had to cart water (very unhealthy) from river… Jim S and a few others came across some discrimination in a pub. An aboriginal was allowed in only because he was with us. The publican said he only prevented aborigines from coming in ‘if they were disorderly’… Left Wellington and arrived in Dubbo about 6.30 pm. Had tea, went for a swim, then to the Dubbo hotel. We noticed a sign above the doorway of the halfway hotel – "Aborigines not allowed in the lounge without the Licensee's permission".' – Ann Curthoys

Monday 14 February

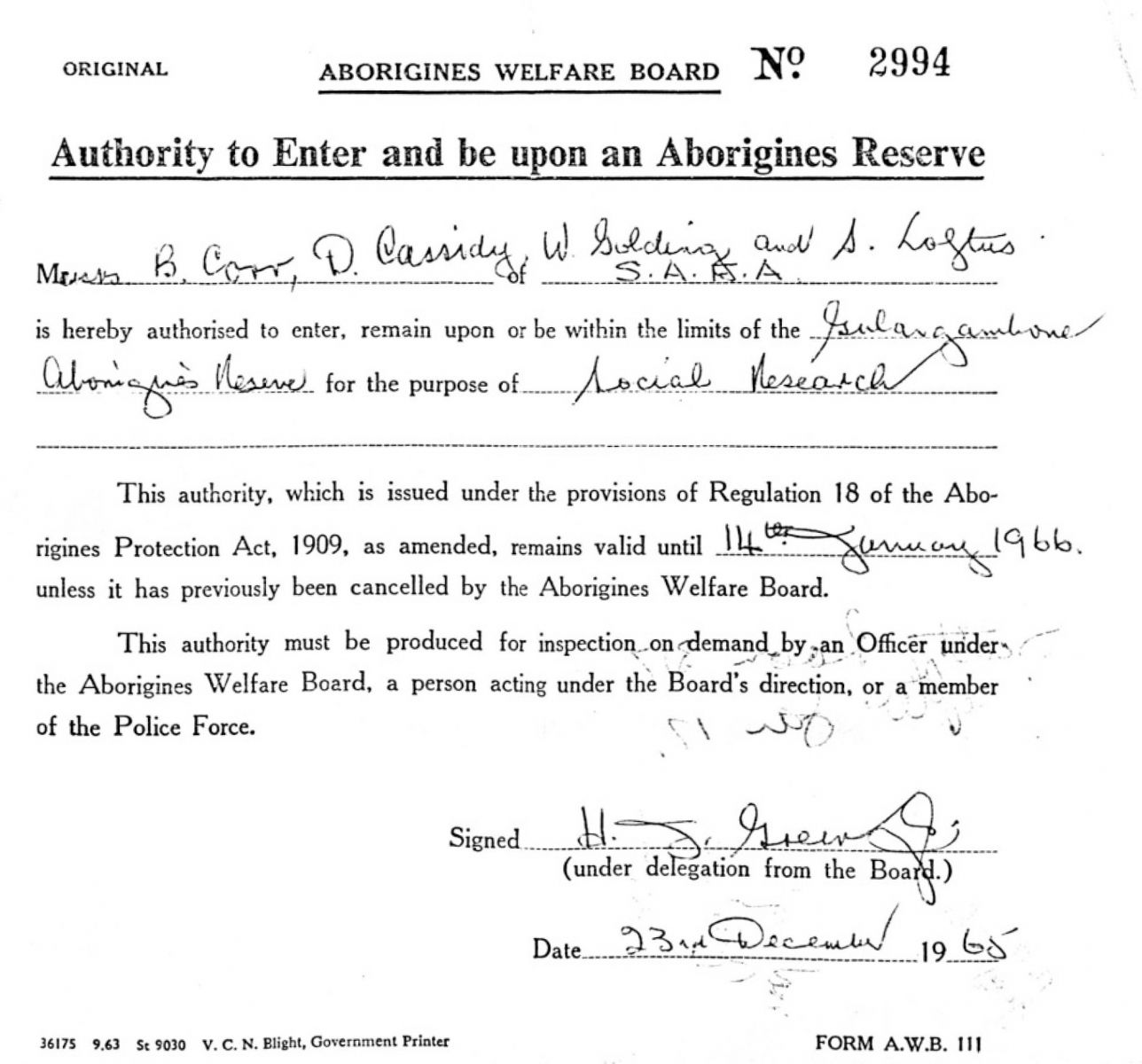

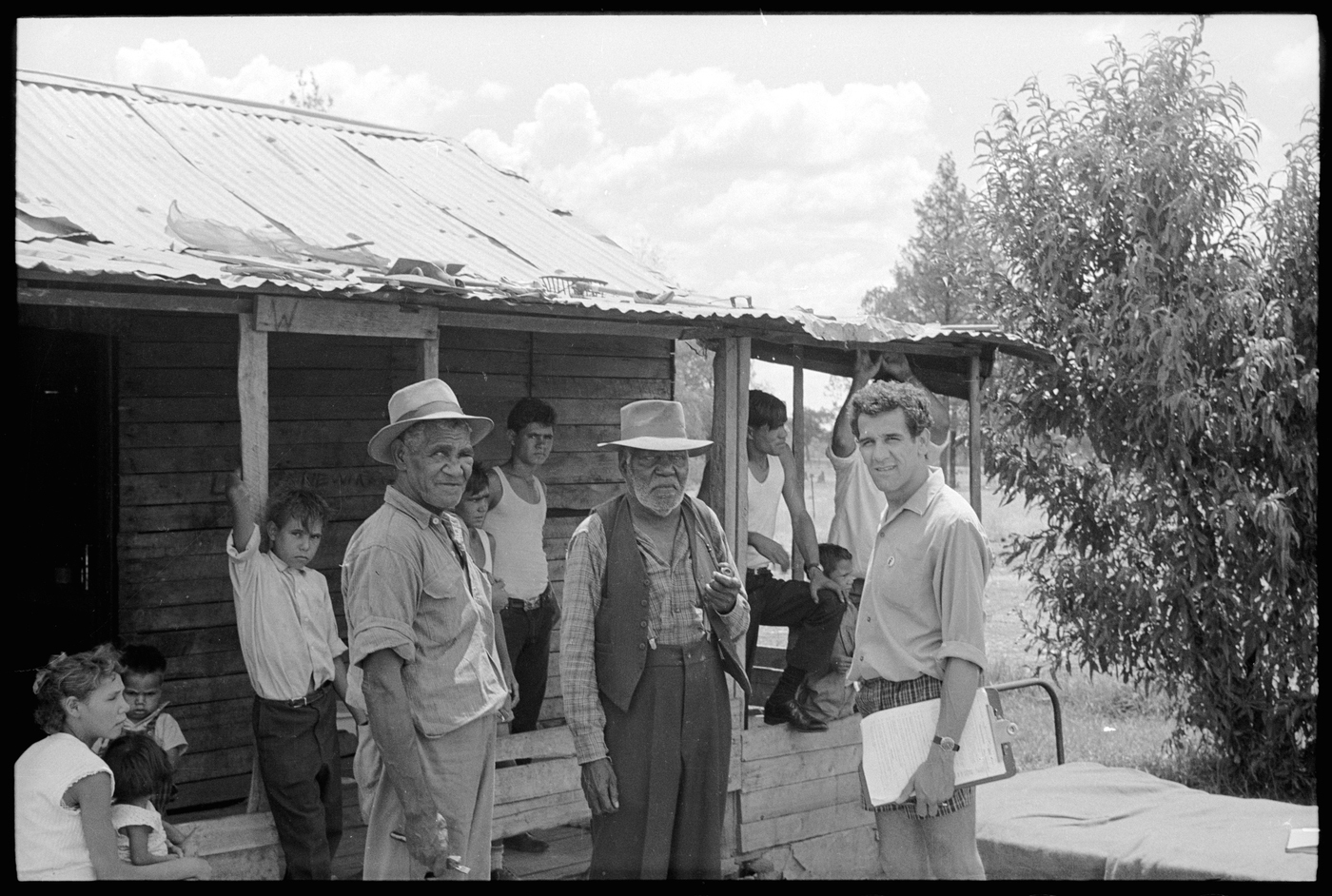

Gulargambone: home of the Wayilwan people

'Heard some radio publicity about us… Only certain aborigines allowed in pub, and aborigines not served in the cafe (the only one)… town jobs for aborigines impossible to get, shearing jobs pay well but are uncertain and seasonal. Welfare board and police very much disliked. Housing very poor.' – Ann Curthoys

Tuesday 15 February

Walgett: on the border between the Wayilwan and Gamilaraay people

'Went to the Namoi River settlement in the morning and did some surveys for a few hours. Most of the people I spoke to very shy and diffident, and said they were quite happy. Conditions very bad - had to use filthy water, tin shacks with mud floors, overcrowded.' – Ann Curthoy’s

'Walgett RSL was famous for entertaining the Aboriginal troops when they came back from World War II. For one day. The next day the majority of the Aboriginal community were banned for good. They were not allowed in any of the hotels and they had to get their beer and were sold cheap plonk through the back windows at three times the price, through sly-grogging operations.

'We took our banners and posters and stood in front of the Walgett RSL. That was in the morning at about eleven o’clock. The heat was tremendous as it was summer-time. We stood there right through until about six o’clock at night, right through in temperatures of one hundred degrees. A couple of the girls fainted and a few of the boys were really exhausted. While we stood there the town came to life like an ant heap. They had never seen anything like it in their lives. People stared. It was a completely new experience, like seeing television for the first time or seeing a moonship fly past their window. Walgett people could not believe it was happening in Walgett. A protest on behalf of the town niggers!' – Charles Perkins

The 'Student Action for Aborigines' banner was a persistent feature of the students' street protests. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Courtesy SEARCH Foundation.

The 'Student Action for Aborigines' banner was a persistent feature of the students' street protests. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Courtesy SEARCH Foundation.

Darce Cassidy recorded the angry conversations and filed a report to the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Captured on tape was the vice-president of the Walgett Returned Service League Club who said he would never allow an Aboriginal person to become a member.

'We just stood in a long line outside the RSL holding placards like "Acceptance, Not Segregation" "End Colour Bar" "Bullets did not Discriminate" "Walgett - Australia's Disgrace" "Why Whites Only" "Educate the Whites" and so on. People gathered round, many jeering, many just watching… At lunchtime many heated discussions broke out. Charlie Perkins spoke terrifically and I think most people listened very attentively. As time went on, more and more aborigines joined in the discussions.' – Ann Curthoys

All the members of the RSL had to pass right past us and they read the banners. They either laughed at us or spat at us or on the banners. Some of them got banners and tore them up. Some of the local smarties wanted to bash a few of us up. They said, ‘You’re stirring up trouble. The dirty niggers don’t deserve any better and they are happy how they are. – Charles Perkins

'A couple of the Aborigines started to talk to me then. I said, "Look, you blokes have to stand up for yourselves. We are willing enough to stand here but you people have to do it from this week on. No one is going to stand up for you but yourselves. If you don’t do it now, your kids will be in the same position as you are when they grow up."

'A few blokes from a big group of whites were becoming really hostile… Suddenly a black woman came out of the crowd, followed by a few other Aboriginal women. They called back to most of the vocal white men: "Listen! You whites come down to our camp and chase our young girls around at night! You were down there last night. I know you!" And she called out some names. "I saw you last night! It’s no good tellin’ me how good you treat us Aborigines. All you do is chase Aboriginal women in the dark. Why don’t you go back and tell your wives where you’ve been? They’re over there in the crowd! Go on, tell them."

'The Aboriginal woman told them off right in front of everybody, yelling at one bloke in particular: "You there, you’re nothing but a gin jockey!"

'When the Aboriginal woman pointed to a few other white fellows, you should have seen that crowd break up. It was as if someone had thrown a bomb amongst them.

'She kept on yelling, "Yes, and you! And you! You were there a week ago! You have been going with my sister for two years in the dark! What about tellin’ your wife about her? Tell her about the little baby boy you’ve given her!" The crowd dispersed in minutes as a result of this Aboriginal woman’s revelations, and Walgett would never be the same again.' – Charles Perkins

Outside Walgett Jim Spigelman trained his home movie camera on the hostile convoy of cars which followed the bus out of town at night and ran it off the road.

'About 200 aborigines and some whites came to see us off. We went off quickly, leaving Alex Mills behind because it was obvious there was considerable hostility in the ranks of the pub leavers. About 3 miles out of town a truck tried to push us off the road. There was a stream of about 10 cars following us and we thought they were full of hostile people and so we were all pretty worried. On the third try he scraped the truck along the side of the bus and forced the bus driver to swerve off the road. It tipped slightly but not right over.' – Ann Curthoys

'I yelled, "Quick, everybody grab a bottle." We were really shaken up and some of the girls were crying. But they grabbed some weapon or other. Jimmy Spigelman and I raced up the front. He had a shoe or some other stupid thing in his hand. I don’t know what he was going to do with that. I had a milk bottle and a Coke bottle and I don’t know what I was going to do with them either.' – Charles Perkins.

Evidence of what was happening was beamed on the evening news into Australian living rooms. It exposed an endemic racism. Film footage shocked city viewers, adding to the mounting pressure on the government.

'As for Gerry Mason, our touring Aboriginal, he was white. He turned white that night. When that bus went off the road he went white. He never got back his blackness until the next morning at Collarenebri… Yet from that point on Gerry was very staunch in support of our cause. He stood with us all the way. He held banners at Moree. He came to believe in Aboriginal rights. It was new for him because he came from one of the quietest tribes in South Australia on the River Murray, near Berri.' – Charles Perkins.

Wednesday 16 February

Moree: home of the Gamilaraay people

'The mission had much better housing etc. than we'd seen anywhere, but there was a manager in control who was apparently very disliked and seemed rather unpleasant.'

'We did the picket, but nobody much came around, and we all boiled, it was very hot. Then we went to the swimming pool. The manager refused to let the six aboriginals in and so we held up our posters and signs. After about 25 mins they let the boys in. Then Charlie arrived with a bus load of 21 aboriginal boys and they had to be all let in.

'We went back to the hall, had tea, and then went off to the Memorial Hall for the public meeting we'd arranged. There were over 200 people there and at first the atmosphere was very hostile, with lots of jeering and interjection.

'Jim Spigelman spoke first, about who we were and how we came to be there. Then John Powles, on the survey. Then Charlie. The questions were sometimes antagonistic but there were some very sympathetic ones too. Then a Mr Kelly got up and moved that the clause in the statute books about segregation in the swimming pool be removed. This was seconded by Bob Brown, and accepted 88 votes to 10. We were all thrilled to bits.' – Ann Curthoys

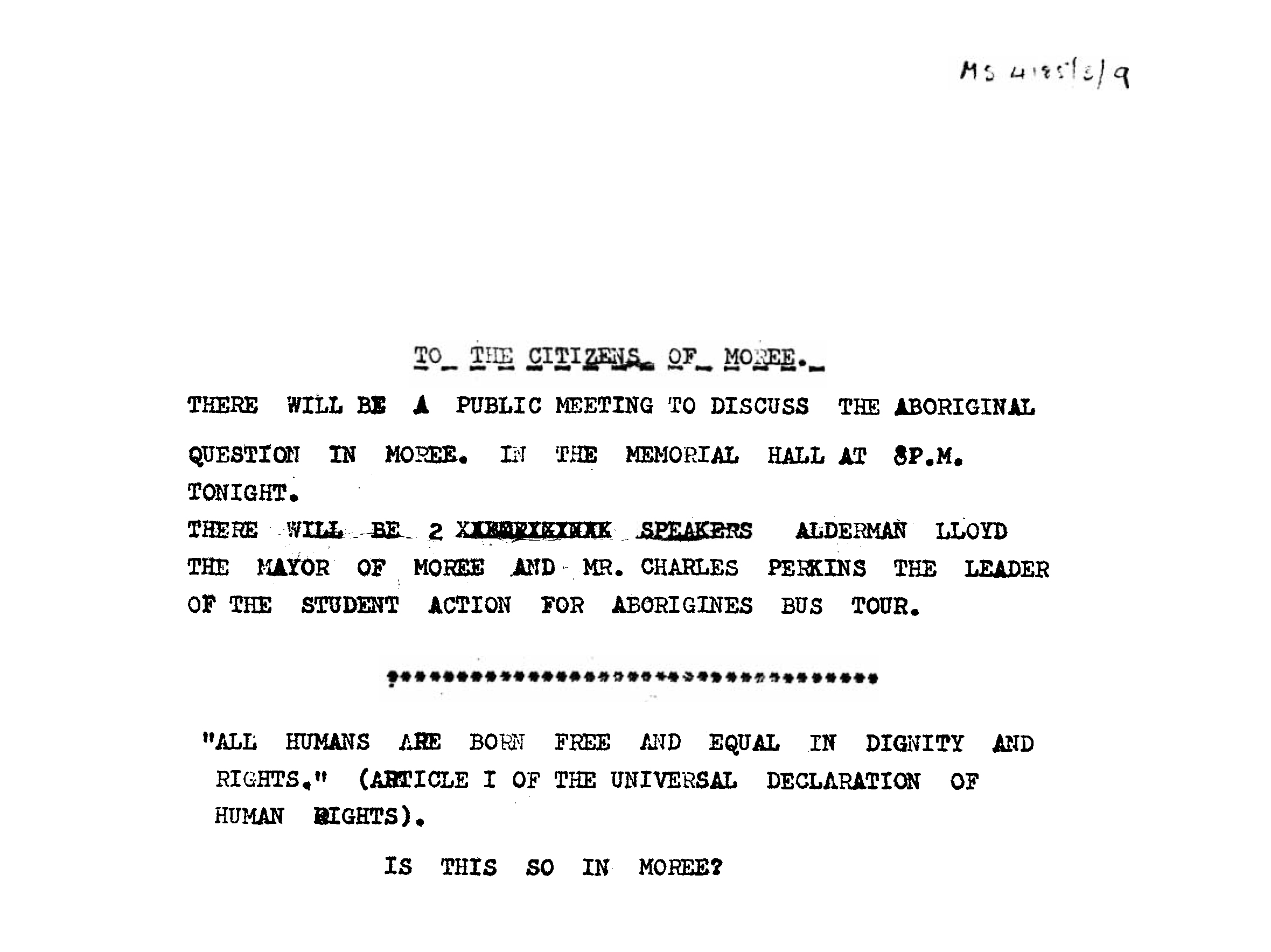

The public meeting notice to the citizens of Moree includes a reference to article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The declaration precedes the United Nations Declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples which was adopted in 2007.

The public meeting notice to the citizens of Moree includes a reference to article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The declaration precedes the United Nations Declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples which was adopted in 2007.

Thursday 17 February

Boggabilla: on the border between the Bigambul and Gamilaraay people

'We went around and spoke to a lot of people. Many of them told us that the manager had told them not to answer our questions, but they intended to do so anyway.

'The houses were weatherboard and very overcrowded. There was no water on, but the river water was taken to taps in the yard. There was no gas or anything, and no electricity (I think). Very often there weren't windows and doors.'

'We heard some terrible stories such as the fact that the police came in the houses without knocking whenever they liked, to find out who had been drinking. Also they ‘did what they liked with the women’. – Ann Curthoys

The bus parked outside the Boggabilla Hotel where the students rested before talking to people on the station. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Courtesy SEARCH Foundation.

The bus parked outside the Boggabilla Hotel where the students rested before talking to people on the station. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Courtesy SEARCH Foundation.

Friday 18 February

Tenterfield: home of the Marbal people

'There we heard from Bob Brown that they day after we left Moree (yesterday) about 60 aboriginal children tried to get in the pool after school. Up to 5.30 about 30 were allowed in, some with Bob Brown, others not. At 5.30 pm the manager refused to allow any more aborigines in and at 6pm the baths were closed (usually they stay open till 8pm). The baths opened again at 7pm and soon after this the mayor stated that the segregationalist statute of June 6th 1955 would be enforced.

'We decided, after much heated discussion, to go straight to Inverell, thus leaving out Tabulam... From there we would go straight to Moree and take strong action of some kind, such as a 24hr picket or something. The decision was unanimous.' – Ann Curthoy’s diary

Saturday 19 & Sunday 20 February

Moree: home of the Gamilaraay people

'On the radio we heard that aboriginal children had been demonstrating outside the Moree baths for the last two afternoons, which was terrific news. All of us are very determined that we are doing the right thing despite the mayor's warning over the radio that our return would cause harm.' – Ann Curthoy’s diary

'We went down to the mission with a few of the students in the bus and we explained to some older Aborigines. Then we went to one particular road in town where a lot of Aborigines live. They were the ‘upper-class adult Aborigines and they did not want anything to do with us at all…So we went back to speak to the young Aboriginal people on the mission: "Yeah we’ll support ya!"' –Charles Perkins

'Charlie started talking to the crowd, but there was a lot of hissing and booing. Then he went to the front of the line and when he refused to move was grabbed and taken away from the line.' – Ann Curthoys

'When we got down to the pool I said, ‘I want a ticket for myself and these ten Aboriginal kids behind me. Here’s the money.’ ‘Sorry, darkies not allowed in,’ replied the baths manager. The manager was a real tough looking bloke too. He frightened me. We decided to block up the gate: ‘Nobody gets through unless we get through with all the Aboriginal kids!’ And the crowd came, hundreds of them. They were pressing about twenty deep around the gate.' – Charles Perkins

'Angry discussion broke out everywhere. I have never met such hostile, hate-filled people. The hostility seemed to be directed at us as university student intruders rather than to the aborigines.' – Ann Curthoys

'The mayor ordered the police to have us removed from the gate entrance. They took hold of my arm and the struggle started. There was a lot of pushing and shoving and spitting. Rotten tomatoes, fruit and eggs began to fly, then the stones were coming over and bottles too.' – Charles Perkins

'The aboriginal children told us that they had been called ‘scabby black ------ niggers’. One child had been knocked down. The poor kids were very frightened. – Ann Curthoys

'The mob from the hotel across the road decided that they were going to show these university students and niggers and black so-and-so’s whose town this was. They came over and did most of the kicking, throwing and punching, and the spitting.' – Charles Perkins

'In all the scuffling Darcy with his tape was knocked down by a man John B and I had been arguing with. Jim S was punched and knocked down in the course of an argument. He lay quite dazed on the ground for a few seconds.

'The police came up and warned us that if we stayed the violence would get much worse. We decided to stay, continuing to insist on being allowed to enter the pool with the aboriginal children. Tomatoes and eggs continued to be thrown.

'Then - breakthrough! The mayor came up to us and stated categorically that he would be prepared to sign a motion to rescind the 1955 statute we were protesting against, and would get two other aldermen to co-sign it.' – Ann Curthoys

'They let the kids in for a swim and we went in with them. We had broken the ban! Everybody came in! We saw the kids into the pool first and we had a swim with them. The Aboriginal kids had broken the ban for the first time in the history of Moree.' – Charles Perkins

'The police then asked us to leave because the crowd was becoming uglier and there were fights breaking out. It was getting dark too. A lot of the blokes were really set on giving us a going-over. The police called in more reinforcements and formed a solid line of police to the bus. It was not very wide and we had to go through it… I was literally covered in spit.' – Charles Perkins

'We walked single file though the crowd who threw eggs, tomatoes, stones, and spat at us. We bundled into the bus and closed all the windows. Eggs and tomatoes were still thrown. Then we all moved off. About 30 cars tried to follow us but the police stopped them.

'We got first place in the 11 o'clock news.' – Ann Curthoys

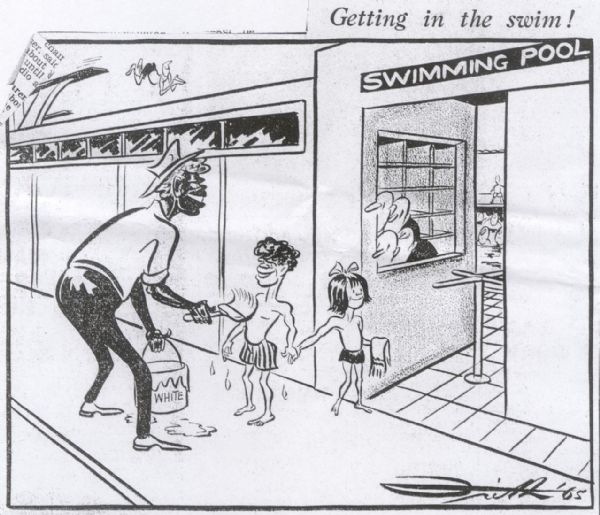

Media coverage including this cartoon in the Tribune helped draw attention to the racism that was happening to Aboriginal people, including children, in Moree. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Media coverage including this cartoon in the Tribune helped draw attention to the racism that was happening to Aboriginal people, including children, in Moree. Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Monday 21 February

Grafton: on the border between the Bundjalung and Gumbaynggir people

'We heard a tape prepared by a Mr Miles, from the ABC. It described the conditions of aborigines on the far north coast, really exposed the complexities of the problem and suggested concrete solutions. There were many recordings of aborigines expressing their views. The tape was prepared two years ago but had never been used - it was too hard-hitting for the ABC.' – Ann Curthoys

Tuesday 22 February

Lismore and Cabbage Tree Island: home of the Bundjalung people

'Cabbage Tree Island was very interesting but the reserve was really very much like any other reserve. The co-op shop was OK and so were some of the houses, but others did not have water or electricity. The manager seemed to be a real bastard.' – Ann Curthoys

Wednesday 23 February

Bowraville: home of the Gumbaynggir people

'We'd hardly arrived when this woman, the president or secretary or something of a local Aborigines Welfare Committee, assured us there was no discrimination in Bowraville, and told us all about how wonderful her committee was.

'A group of us went out to the reserve which was about one and a half miles out of town. It was controlled by the Welfare Board but didn't have a manager… The conditions were very bad. The houses were weatherboard, very run down, and hadn't been looked after for 15 years (the houses were 26 years old). They were extremely overcrowded.

'The general picture we got from talking to the people on the reserve was one of extreme lack of job opportunity… The discrimination in the town was absolutely shocking - by far the worst we'd encountered.

'We learnt there was a partition in the picture theatre separating the aborigines from the whites. The aborigines had to buy their tickets separately and could only enter the theatre after the picture had started.

'We learnt of a number of segregated pubs and cafes, and of instances of segregation in the school about 6 years earlier. The two populations were almost completely separate. At first we weren't sure where to start - the town was just so bad. We thought the press could blow up a big story about it, but they refused, obviously instigating us to put on a demonstration.

'We decided to first go up to the manager of the picture theatre, who had previously told Hall that he would let no aborigines in the back of the picture hall, including Charlie Perkins. We went up to see him but he refused to answer the door. The press got a photo of him opening the door slightly and shut it.' – Ann Curthoys

Thursday 24 February

Kempsey: home of the Dhanggati people

'The general picture in Kempsey re discrimination was that everything was fair (a cafe here and a pub there excepted), but the segregation of the swimming pool was the most outstanding thing.

'We took about 10-15 kids with us to the swimming pool. They weren't allowed in and neither were Charlie or Gary. Absolutely blatant.

'Charlie was very emphatic about the success of it because of the publicity, but most of the rest of us thought it an absolute flop because we had failed to force the issue within Kempsey itself. We all realised Kempsey had ignored us, which was precisely what we didn't want. – Ann Curthoys

Friday 25 February

Taree: home of the Birpai people

'Stopped at the Purfleet reserve for half an hour, talking to the people there.' – Ann Curthoys

Saturday 26 February

Sydney: home of the Eora people

'We got all tense etc near the end, because of the press conference. Had tea at Hornsby and then drove on to Uni. When we arrived there was Ted Noffs, a few pressmen, some parents etc. and that's about all. No aborigines or other supporters. We found out later that Noffs had deliberately not told anyone where and when we were arriving.' – Ann Curthoys

Aftermath

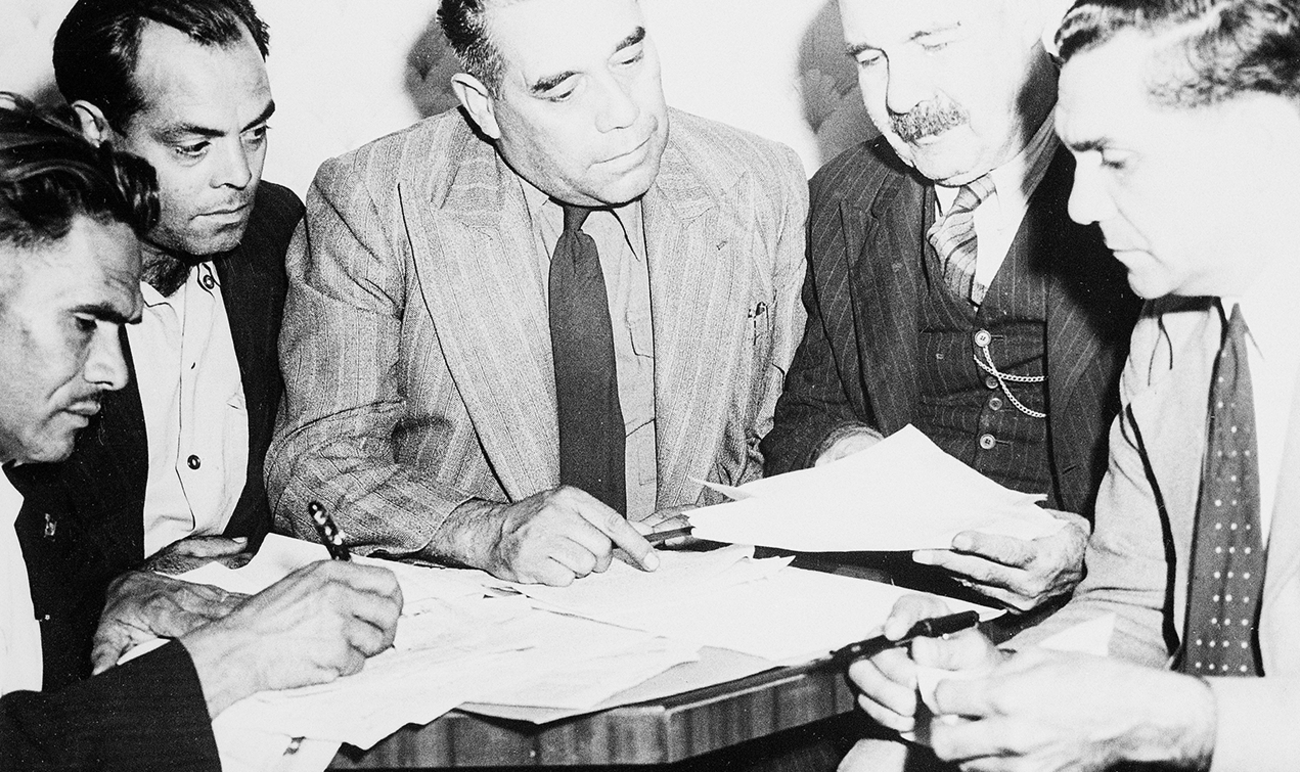

Charles Perkins reported the events to a crowd of 200 people at the 1965 Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) conference in Canberra. 'The problem is out in the open now', he told them. He called for necessary follow-up work such as the building of relationships with local Aboriginal groups and improved services and access to education for Aboriginal residents in western New South Wales towns. Conference goers heard that one positive result of the students' activities was that the NSW Aborigines Welfare Board publicly announced that it would spend sixty-five thousand pounds on housing in Moree.

Later in the year, Harry Hall, president of the Walgett Aborigines' Progressive Association, appealed to Perkins and other Aboriginal activists to return to Walgett to assist in the fight against the colour bar being applied at the Oasis Hotel. Perkins and others returned to help.

The SAFA engaged in further visits to country towns later in the year but, by the end of 1966, it was finished as a political force.

The 1965 Freedom Ride through New South Wales towns and the publicity it gained, including in overseas newspapers such as the New York Times, illuminated to the world the racial discrimination happening in Australia. While the life of the SAFA was relatively short, the Ride had a lasting impact and served to strengthen the campaigns that followed to bring about greater equality and recognition for Aboriginal people.